Alkali-Aggregate Reaction in Concrete

A World Review

- 768 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Alkali-Aggregate Reaction in Concrete

A World Review

About this book

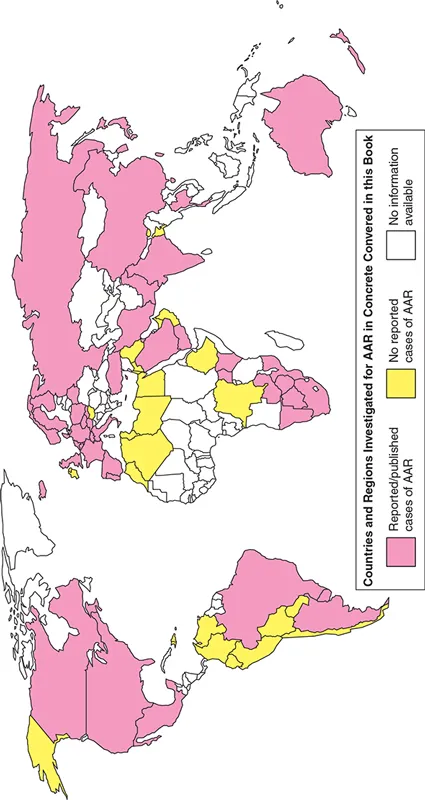

Alkali-Aggregate Reaction in Concrete: A World Review is unique in providing authoritative and up to date expert information on the causes and effects of Alkali-Aggregate Reaction (AAR) in concrete structures worldwide. In 1992 a first edition entitled The Alkali-Silica Reaction in Concrete, edited by Professor Narayan Swamy, was published in a first attempt to cover this concrete problem from a global perspective, but the coverage was incomplete. This completely new edition offers a fully updated and more universal coverage of the world situation concerning AAR and includes a wealth of new evidence and research information that has accumulated in the intervening years.

Although there are various textbooks offering readers sections that deal with AAR deterioration and damage to concrete, no other single book brings together the views of recognised international experts in the field, and the wealth of scattered research information that is available. It provides a 'state of the art' review and deals authoritatively with the mechanisms of AAR, its diagnosis and how to treat concrete affected by AAR. It is illustrated by numerous actual examples from around the world, and comprises specialist contributions provided by senior engineers and scientists from many parts of the world.

The book is divided into two distinct but complementary parts. The first five chapters deal with the most recent findings concerning the mechanisms involved in the reaction, methods concerning its diagnosis, testing and evaluation, together with an appraisal of current methods used in its avoidance and in the remediation of affected concrete structures. The second part is divided into eleven chapters covering each region of the world in turn. These chapters have been written by experts with specialist knowledge of AAR in the countries involved and include an authoritative appraisal of the problem and its solution as it affects concrete structures in the region.

Such an authoritative compilation of information on AAR has not been attempted previously on this scale and this work is therefore an essential source for practising and research civil engineers, consultant engineers and materials scientists, as well as aggregate and cement producers, designers and concrete suppliers, especially regarding projects outside their own region.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Introduction, Chemistry and Mechanisms

1.1 Background

| Country/Region | Examples of potentially Reactive aggregate types | Some Reported Case of AAR | Comments and References | Chapter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | 6,7 & 8 | |||

| Austria | Sedimentary sands and gravels | Roads, pavements dams | Quartzite and gneisses identified as reactive | 8 |

| Belgium | Quaternary sands and gravels, argillaceous limestone, quartz diorite, dacite | Bridges, bridge decks, hydro structures | 150 structures affected Denmars (2012); | 8 |

| Cyprus | Crushed opaline siliceous limestone, river and beach gravels | Marine structures buildings | Poole (1975); Siliceous reef limestone aggregate with high water absorption (3.3); | 8 |

| Czech Republic | Granodiorite, quartzite, phyllite, acid volcanics, quartz-feldspar tuffs, siliceous limestone | Highway structures, bridges, airport pavements, dams, tunnels | Cryptocrystalline quartz identified as reactive in a range of rock types | 8 |

| Denmark | Opaline flint, calcareous flint, microporous flints | Swimming pools Bridges, roads | Cements low alkali, external sources may contribute alkali. Marked pessimum behaviour. Rapid reaction. Nielson et al. (2004); | 7 |

| France | Siliceous limestone, quartzite, Rhône gravels, meta-granite and gneiss in Alpine region | Dams, bridges, retaining walls | ASR in over 400 structures, 10 demolished. Most in N. France and Brittany. Some cases complicated by DEF and sulfate attack | 8 |

| Finland | Pre-Cambrian gneiss, cataclasites, mylonites | Bridges, housing, industrial buildings | 70+ structures identified. Confused with freeze-thaw. Air entrainment & ggbs in common use. Local cement high-alkali. Pyy et al. (2012); | 7 |

| Germany | Opaline sandstone, flint, greywacke, siliceous limestone | Bridges, highway pavements, precast slabs | First identified early 1950s, typically rapid reaction time | 8 |

| Hungary | Sands and gravels, carbonates and volcanics | None reported | Only andesite potentially reactive. Common use of ggbs cementreplacement | 8 |

| Iceland | Sea dredged basalt, andesite, rhyolite, aggregates containing secondary opal | Domestic housing, hydraulic structures, pavements | Early cements are high alkali. Fly ash, pozzalans & silica fume in common use. Wigum et al. (2009/10); | 7 |

| Italy | River sands and gravels and carbonates containing chert, jasper, chalcedony | Residential and industrial buildings, pavements | Barisone, G. & Restivo, G. (1992b); | 8 |

| Netherlands | River sands and gravels | Bridges, viaducts, tunnel linings | Sea dredged gravel non-reactive common use of pfa. Broekmans (2002); | 8 |

| Norway | Sandstones, greywacke, claystone, mylonite, cataclasite, acid volcanics | Bridges, hydraulic structues, precast units, foundations, pipes, dams | Typically slowly reacting, use of fly ash in cement to mitigate ASR. Wigum et al. (2004); | 7 |

| Poland | Sands and gravels containing opal and chalcedony, sandstone, siliceous limestone and dolomite | Viaducts, buildings, precast elements | Large producer of aggregates, but variable quality. Góralczyk (2001); | 8 |

| Portugal | Granitoid types, basalts | Dams, bridges | Mostly slow reaction ASR (Silva et al., 2016); Dolomite + crypto crystalline silica are potentiallyreactive. | 8 |

| Republic of Ireland | Chert and greywacke | None reported | Some high alkali cements | 6 |

| Slovenia | River sands and gravels, opaline breccia | Concrete columns | ASR in floor due to crushed glass contamination | 8 |

| Spain | Quartzite, granodiorite, granite, monzonite, schist, slate | Hydraulic structures, dams, bridges | Quartzite and monzonite with micro and crypto crystalline quartz fast reacting others slow | 8 |

| Sweden | Gravels with porous flint, limestone with ... |

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Editors and Authors

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Introduction, Chemistry and Mechanisms

- 2. Assessment, Testing and Specification

- 3. So-Called Alkali-Carbonate Reaction (ACR)

- 4. Prevention of Alkali-Silica Reaction

- 5. Diagnosis, Appraisal, Repair and Management

- 6. United Kingdom and Ireland

- 7. Nordic Europe

- 8. Mainland Europe, Turkey and Cyprus

- 9. Russian Federation

- 10. North America (USA and Canada)

- 11. South and Central America

- 12. Southern and Central Africa

- 13. Japan, China and South-East Asia

- 14. Australia and New Zealand

- 15. Indian Sub-Continent

- 16. Middle East & North Africa

- Index