![]()

1

Introduction

J. Bruce Jacobs

To an extraordinary degree, Taiwanese ask themselves, “Who are we?” This question lies at the heart of “identity”. And, to a surprising degree, as Taiwan has democratized, the answers to this question have changed considerably.

To understand these changes, we have to understand a bit of Taiwan’s history. Today, we can best divide Taiwan’s history into three large stages. The first historical stage begins about 6,000 years ago and continued until 1624, when the Dutch first invaded. Modern archaeological evidence demonstrates that Taiwan’s indigenous (or aboriginal) peoples developed strong trading networks with Southeast Asia in what is now the Philippines, eastern Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam and Cambodia. No such links have been discovered with China. Metal technologies too were imported from Southeast Asia and not China. Dutch evidence demonstrates that Taiwan’s indigenous peoples had relatively egalitarian societies, that they had excellent physical health, that they were physically much larger than the Dutch and that their substantial villages had excellent construction and design (Jacobs 2016a).

The second historical stage, colonialism, began in 1624 with the arrival of the Dutch and ended in 1988 with the death of President Chiang Ching-kuo. During this 364-year stage, six colonial governments ruled at least parts of Taiwan. These were (i) the Dutch (1624–1662), (ii) the Spanish (1626–1642), who ruled northern Taiwan during the first part of the Dutch period, (iii) the Zheng family regime (1662–1683) founded by Zheng Chenggong (Koxinga), though he himself died within five months of forcing the Dutch to withdraw, (iv) the Manchu empire (1683–1895), (v) the Japanese (1895–1945) and (vi) the Chinese Nationalists (Kuomintang [KMT] or Guomindang) under Chiang Kai-shek and Chiang Ching-kuo (1945–1988). Under all of these regimes, a small minority of outsiders ruled the native Taiwanese in the interest of the outsiders (Jacobs 2011, 2012, 2013). As Albert Memmi has pointed out, colonial regimes have “racism” at their heart and Taiwanese suffered under all of these regimes, which systematically discriminated against Taiwanese (Jacobs 2014, p. 53).

It must be emphasized that no foreigners (including Chinese) established permanent communities in Taiwan before the arrival of the Dutch. Chinese merchants, fishermen and pirates would come to visit Taiwan temporarily to trade, fish and hide, but they all went back home and none built communities on the island. It was the Dutch who first imported Chinese for labor.

Through the more than three centuries of colonial rule, the definition of a “Taiwanese” began to change. Of course, the indigenous population was “Taiwanese”, but Chinese migrants too began to identify with Taiwan. According to Harry Lamley, one of the world’s most eminent scholars of Taiwan history, this identification with Taiwan began in the 1860s and increased greatly during the Japanese period (Jacobs 2014, p. 56; Lamley 1981, pp. 312, 314).

This change of identity is important for understanding Taiwan as well as for understanding wider world history. Migrants do change their identity when they migrate. People in Australia, Canada and New Zealand no longer see themselves as British. Chinese migrants are no exception. However, in China today, there is a perception that anyone with some “Chinese blood” (whatever that is) remains Chinese for ever and ever. The falsity of such a claim was demonstrated with the appointment of Gary Locke as American ambassador to China (2011–2014). Locke looked Chinese, but he did not act Chinese and could not even speak Chinese. Unlike Chinese officials, he carried his own bag, flew economy and took his children for hamburgers to McDonald’s in Beijing. Gary Locke was an American, not a Chinese, despite having “Chinese blood”.

Thus, the definition of what constitutes a “Taiwanese” changed over time. Initially, it included only the indigenous people. But, as migrants from abroad came to Taiwan and recognized it as home, they too became Taiwanese. Today, the term “Taiwanese” includes any persons who live in Taiwan and who believe themselves to be Taiwanese irrespective of whether their ancestors resided in Taiwan or overseas. Thus, the term now includes Taiwan’s indigenous peoples, people whose ancestors migrated from China in past centuries, more recent Chinese migrants and migrants from Southeast Asia and elsewhere.

For those who may doubt that the Chinese Nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek and Chiang Ching-kuo constituted a colonial government, let us compare their regime with that of the Japanese, which everyone agrees was colonial. Comparison reveals that the two regimes shared at least six characteristics in terms of their nature and in terms of the timing of their policies. First, both systematically discriminated politically against Taiwanese, who at best were second class citizens. Neither allowed Taiwanese to hold senior positions. Under Chiang Kai-shek and Chiang Ching-kuo, although Taiwanese accounted for 85–90 per cent of the population, no Taiwanese ever held such positions as president, premier, minister of foreign affairs, minister of national defence, minister of education, minster of economics, minister of finance, minister of justice, director of the Government Information Office or any senior military or security position. Under both Chiangs, Mainlanders – those Chinese who went to Taiwan with Chiang Kai-shek in the late 1940s and constituted 10–15 per cent of Taiwan’s population – always formed a large majority of both the KMT’s Central Standing Committee and the government’s cabinet.

Secondly, both regimes killed thousands of Taiwanese in their first years of rule. Under Chiang Kai-shek, this included the mass slaughters following the 28 February (1947) Movement. Third, both regimes began with twenty-five years of high oppression. Under Chiang Kai-shek, this was the time of the White Terror. Fourth, owing to both domestic and international pressures, both regimes “liberalized”. Under Chiang Kai-shek and Chiang Ching-kuo, these pressures included Taiwan’s withdrawal/expulsion from United Nations, the Diaoyutai Movement and the demands for reform from The Intellectual Magazine (Daxue zazhi 大學雜誌), as well as the promotion of Chiang Ching-kuo to the premiership in 1972 – a key step in his succession – which led Chiang Ching-kuo to reform in order to gain support. Fifth, both regimes again became repressive after Japan initiated World War II in the Pacific and the KMT government suppressed the opposition after the Kaohsiung Incident of 10 December 1979.1 Finally, both regimes tried to make Taiwanese speak their “national language” 國語 (Japanese kokugo; Chinese guoyu), Japanese and Mandarin Chinese respectively, as part of their larger cultural attempts to make Taiwanese second-class Japanese and Chinese (for details, see Jacobs 2013, pp. 573–575).

Thus, all of these six colonial regimes were dictatorships that repressed the Taiwanese people and their aspirations. Under colonialism, overt “Taiwanization” was repressed and remained politically impossible.

The third historical stage begins after the death of President Chiang Ching-kuo on 13 January 1988 when Vice-President Lee Teng-hui became Taiwan’s first Taiwanese president. Lee, working together with reform elements of the ruling Nationalist Party (KMT) and with members of the new opposition Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), slowly and gradually established and consolidated democracy in Taiwan.2 As noted above, colonial governments did not allow any expression of Taiwanese nationalism, though there were some movements advocating Taiwanization during the 1920s under the Japanese (Chen 1972) and also in the early to mid 1980s before Chiang Ching-kuo’s death (Jacobs 2005). Only with democratization could Taiwan nationalism flourish.

Key political issues and political divides revolved around the questions, “who are we?” and “what are we?” Is Taiwan, called the Republic of China, a continuation of Chiang Kai-shek and Chiang Ching-kuo’s pretence that Taiwan is part of China? Certainly, President Ma Ying-jeou (2008–2016) thought so, though it must be pointed out that he campaigned in 2008 on a platform of being Taiwanese, saying that he was conceived in Taiwan (though he was born in Hong Kong) and that he was raised on Taiwan water and Taiwan rice. However, and this gets to the heart of the matter, Taiwan’s voters overwhelmingly rejected his KMT in the 29 November 2014 local elections and the voters thrashed the KMT in the presidential and legislative elections of 16 January 2016. These election results derived both from voter anger at his pro-China policies as well as from his administration’s incompetence.

But, the development toward a “Taiwanese Taiwan” rather than a “Chinese Taiwan” took place gradually. President Lee Teng-hui initially was quite cautious, a wise policy since the minority Mainlanders held many of the levers of power. Although Lee did move toward a sense of Taiwaneseness, he also supported the election of KMT candidate Lien Chan in the 2000 presidential election. Only after DPP candidate Chen Shui-bian won the presidency in 2000 did Lee Tenghui publicly become an outright Taiwan nationalist.3

In the world today, there is a widespread impression that Taiwan is “Chinese”. This comes from the Chinese colonial regime under Chiang Kai-shek and Chiang Ching-kuo. In fact, a Chinese regime, based in China, has only ruled Taiwan for four years during its 6,000 year history – from late 1945 to late 1949 during the Chinese Civil War. These four years, with the mass slaughter of Taiwanese throughout the island by Chiang Kai-shek’s military, were the worst four years in Taiwan’s 6,000 year history. Chiang Kai-shek followed up with his White Terror, when he imprisoned and executed many innocent people.

Yet, it is absurd to focus on the Chiang Kai-shek and Chiang Ching-kuo governments to determine whether or not Taiwan is Chinese. Do people today say that India or Pakistan or Bangladesh is British because the British had a colonial government there? Do people today say that Algeria or Vietnam is French because the French ruled those countries as colonies? Of course, they do not. Furthermore, we have also previously noted the important point that migration changes identity and that past ancestry does not determine who one is today.

Thus, Taiwan – like Australia – has undergone a huge change in how it answers the question, “who are we?” Fifty years ago, many Australians who were born and bred in Australia and who had never left the country talked about “going home”, by which they meant Britain. No Australian talks like that anymore! Similarly, a major shift in response to the question “who are we?” has also occurred in Taiwan. We explore this significant cultural change in the next section.

Identity surveys in Taiwan

Many surveys in Taiwan conducted by the media, political parties and academic institutions have explored the question “who are we?” Although the absolute numbers vary, the trends in all of the surveys are the same: the proportion of people in Taiwan saying that they are “Chinese” is falling substantially, while those who say they are “Taiwanese” is increasing very rapidly. Of all these surveys, my favorite is that conducted by the Election Study Center at National Chengchi University, and several of our chapter authors have cited this survey.

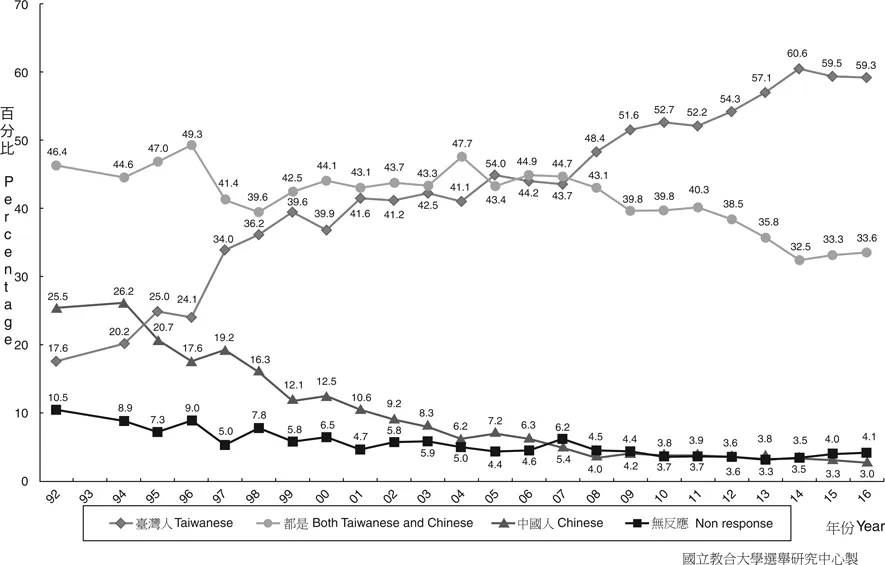

Beginning in 1992, during the early years of democratization, the Election Study Center every six months asks a substantial sample whether they are “Chinese”, “Taiwanese” or “both”. With minor blips in the data owing to sampling, the data show clear trends (see Figure 1.1).

The line marked with diamonds ◆ represents those who say they are Taiwanese. This number has steadily risen from about one in six persons (17.6 per cent) in 1992 to about three in five persons (59.3 per cent) in June 2016. Interestingly, the proportion saying that they were only Taiwanese passed the 50 per cent mark just a month after the so-called pro-China president Ma Ying-jeou was inaugurated for his first term. With blips in the data, the proportion of those claiming to be only Taiwanese has steadily increased. The proportion claiming they are only Taiwanese is now more than three times than in 1992.

The line with triangles ▲ represents those who claim they are Chinese. This figure was more than one-fourth of Taiwan’s population (25.5 per cent) in 1992,

Figure 1.1 Changes in Taiwanese/Chinese identity of Taiwanese as tracked in surveys by the Election Study Center, NCCU (1992–2016)

but has now dropped to 3.0 per cent, less than one-eighth its original number. In 1992 this number clearly included many people whose families had lived in Taiwan for decades, but now many people of Mainlander background no longer believe they are only Chinese.

The line with circles ● indicates those who say they are both Taiwanese and Chinese. Unlike the trends for Taiwanese and Chinese, this line has bounced around considerably. In general, however, it has declined moderately from the high 40s in the early 1990s to the low 30s in the past few years. On the basis of further research by scholars at the Election Study Center, we know that many people who originally stated that they were Chinese moved first to stating they were both Taiwanese and Chinese before moving to the Taiwanese category. This double movement has taken place among all of Taiwan’s four main ethnic groups (Indigenous, Hokkien, Hakka and Mainlander), though, of course, Hokkien had a much higher number of Taiwanese and a much lower number of Chinese identifications than did, for example, the Mainlanders. But even among Mainlanders, the identification as Chinese dropped dramatically, from 55.6 per cent of Mainlanders in 1994 to only 29.9 per cent in 2000 (Ho and Liu 2003). Since 2000, the declines in Chinese identification among Mainlanders in Taiwan have continued.

The final line with squares ◼ gives the results for those who refuse to answer or do not know. This line steadily declines from 10.5 per cent in 1992 to 4.1 per cent in June 2016. It is not surprising that this non-response rate was high in 1992, soon after the start of democratization when people feared that answering a survey could hurt them should democratization fail and future dictators use the data to hunt “dissidents”. Yet, even more interestingly, the low non-response rate means that people in Taiwan do talk about “who we are” and very, very few people do not have an answer to that question.

The relatively large numbers who stated that they were Chinese and the relatively low numbers who stated that they were Taiwanese in 1992 were clearly affected by the Chinese nationalist education taught in the schools under Chiang Kai-shek and Chiang Ching-kuo. As democratization expanded with an ever more free-wheeling media environment, Taiwanese became much happier to state that they were in fact Taiwanese.

Like all research methods, surveys have their advantages and their disadvantages. From very different perspectives, Tanguy Lepesant and Stéphane Corcuff in their chapters both criticize such broad surveys, and much of their criticism is valid. Yet, such surveys still remain critical to our understanding of basic trends in how Taiwanese identify themselves and they provide a base upon which various critics can and do build.

While such surveys are now almost passé in Taiwan, interestingly they confuse Chinese who cannot understand them. Chinese work in an environment that does not allow challenges to the truth received from above. The Chinese Communist Party states that Taiwanese are Chinese, yet these surveys show that Taiwanese believe they are Taiwanese and not Chinese. Thus, many Chinese visiting Taiwan or participating in “cross-strait” conferences find such survey data confronting and confusing.

The ch...