Constellation noir: the gothic roots of surrealism

On 14 April 1921 the group of young writers gathered around André Breton, including Louis Aragon, Tristan Tzara, Benjamin Péret and Jacques Rigaut, together with friends and lovers, made a short excursion in Paris to the decayed medieval church of Saint-Julien-le-Pauvre. Posing in photos sheltering under umbrellas from the spring showers, the fashionably dressed visitors were there to stage a dada event, attracted to the church as Mark Polizzotti describes, ‘less for its obvious religious affiliations than for its atmosphere of medieval desolation’.2 But the church also holds particular significance for a nascent surrealist movement on the verge of a long journey. Contemporaneous with nearby Notre Dame, Saint-Julien is geographically located on the old Roman road that forms the pilgrims’ route (El Camino de Santiago – the ‘Milky Way’), guided by stars to the shrine of Saint James at Santiago de Compostela, such that the event’s retrospective symbolic resonance – at which Breton ‘read a manifesto’ – extends far beyond the low-key demonstration staged that day.3

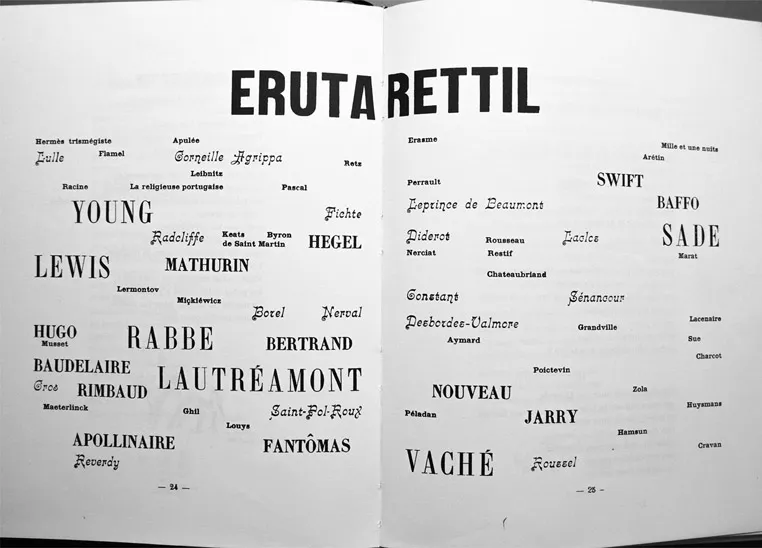

In the immediate wake of the First World War Breton’s group had launched the journal Littérature, where we can trace their literary tastes and ideas on the eve of the launch of the surrealist movement.4 The double issue of October 1923, devoted to poetry, included a layout under the ‘mirrored’ heading ‘ERUTARETTIL’ (Figure 1.1), suggestive of an inversion of literary values, and set out the group’s literary firmament in font sizes that reflect the relative luminance of those celestial bodies against an imaginary night-sky.5

Some names figure there as isolated stars, among the most prominent of which are those of Lautréamont and Jacques Vaché, Breton’s wartime friend from his time at Nantes. Others appear loosely organised according to various themes or constellations, as with a group of English writers that includes the ‘graveyard’ poet Edward Young, alongside a cluster of gothic novelists, including Matthew Lewis, Ann Radcliffe and Charles Maturin. The inclusion of Young, best known for Night Thoughts (1742–46), his great anguished hymn to the night, a meditation on mortality – ‘surrealist from cover to cover’ according to Breton – roots surrealism’s reading of the gothic in that earlier, more elegiac moment.6 Lewis attained notoriety for his gothic novel The

Figure 1.1 ‘Erutarettil’, Littérature, New series, nos. 11–12, October 1923, pp. 24–25

Monk (1796), followed soon after by his sensational play The Castle Spectre (1798). Maturin, an Irish clergyman is best known for his Melmoth the Wanderer (1820), while Radcliffe was celebrated for a series of expansive gothic novels notable for their descriptions of sublime landscapes and mysterious castles.7 Other names included here, though not specifically ‘gothic’, share the same ambiance, as with ‘La religieuse portugaise’ – most probably a reference to Les Lettres Portugaises (1669).8 We can also identify a constellation of magicians and occultists at the very top of the chart, including the German occultist Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, the Catalan philosopher and mystic Ramon Llull, the French alchemist Nicolas Flamel, as well the mythical Graeco-Egyptian figure Hermes Trismegistus, representing the hermetic tradition and pointing us to another trajectory that surrealism would eventually pursue, and which we analyse in a later chapter.9 Pétrus Borel, the self-styled ‘lycanthrope’ and a great favourite with Breton, has been considered as ‘gothic’ for tales such as ‘Andreas Vasalius the Anatomist’ (1833) and for his novel Madame Putiphor (1839).10 The hermetic tradition also inspired the writings of Gérard de Nerval, a friend of Borel and a translator of Faust, and whose early play ‘The Alchemist’ (1839) was based on the life of Flamel – a strand that we pursue in Chapter 6.11 The interweaving of dream and reality in his Aurélia, ou Le Rêve et la Vie, left incomplete on his suicide in 1855, posing dream as a ‘second life’, further situates Nerval within the gothic tradition, anticipating concerns central to Breton’s own work.12 This all therefore heralds an inversion by surrealism of early criticisms of gothic writing for the genre’s invoking of the irrational and the supernatural, instead celebrating precisely those qualities. The inclusion here of the name of Fantômas, the master criminal villain of Souvestre and Allain’s epic serial also points to the direction in which the gothic would mutate during the course of the nineteenth century, particularly in the detective mystery as pioneered by Poe.13 And the name of Charcot signals the significance of the melodramatic theatre of hysteria developed at the Salpêtrière hospital where Freud carried out some of his early training. Finally, we should note here the inclusion already of Sade, a crucial figure in relation to the theorisation of gothic literature, whose importance to surrealism would only continue to expand and whose ideas dominate the final chapter.

Both Breton and Antonin Artaud – himself a key member of the surrealist group between 1924 and 1926 – deployed the gothic during the interwar phase of surrealism, not simply as a badge of literary taste or inspiration, but more importantly as a vehicle through which to develop crucial areas of their thought. Alienated not least by the war, for both men the gothic novel provided the paradigm of the individual in radical conflict with societal norms on the model of the ‘accursed outcast’, whether in Lewis’s Monk or Maturin’s Melmoth, or the yet more hyperbolic writing of Lautréamont. For Breton, the model of the gothic novel enabled him to refract contemporary concerns – the pursuit of desire, the femme fatale, alternative forms of socialisation, and specific loaded motifs such as the castle, night, or the forest – through the optic of romanticism’s darker cognate. Crucially, the gothic provided for Breton a paradigm of the blurring and eventual erasure of the boundaries between dream and reality – a particular focus of this chapter – and between reason and madness, the rational and the irrational. For Artaud, too, the gothic provided the vehicle through which to realise themes such as violence, melodrama, incest and theatricality, ideas central to his development of the Theatre of Cruelty during the early 1930s.14 For both men, too, their rejection of reliance upon reason and their turn instead to the irrational, the occult and magic found an echo in the gothic: Artaud turned to magic and the production of ‘spells’ during the thirties, while magic and its relationship with art and architecture were to become a major preoccupation with Breton, particularly after the Second World War. For Breton and surrealism, the gothic also provided a means through which to attack Catholicism, a central plank of surrealist strategy during the 1930s, while for Artaud, more conflicted in his relationship with religion, it provided the framework for a more divided and nuanced critique. And finally we could say that the gothic provided for all surrealist writers, as well as for visual artists such as Max Ernst and Man Ray, a model of transgression – as with their deployment of the figure of Sade – situating their work on the fringes of society and reaffirming their avant-garde credentials.

The gothic has been posed by critics such as David Punter, Maggie Kilgour and others as a kind of ‘return of the repressed’ – as what Kilgour characterises as a ‘resurrection of the need for the sacred and transcendental’ in a modern, secular world, and as a reaction against a neo-classical ideal of order and unity.15 Engaging with such territory clearly entailed certain dangers for a movement rigidly opposed to all forms of religion, contributing to tensions that would come to a head in 1951 with the so-called ‘Carrouges Affair’. The gothic novel is posed by Kilgour as a transitional form that first raises themes later developed in a more sophisticated manner by romanticism, and like romanticism, ‘a revolt against a mechanistic or atomistic view of the world and relations, in favour of recovering an earlier organic model’.16 For romanticism, Kilgour observes, ‘art is able to recover the paradise lost of childhood’, noting that childhood is a central motif of the gothic and claiming support in Breton’s observation that: ‘A work of art worthy of its name is one which gives us back the freshness and the emotions of childhood’ – though as we will see, surrealism’s relationship with childhood is also marked by deep ambivalence.17

Martin-Christoph Just maintains that the gothic novel essentially engages with the fears and anxieties of its readers, usually through the intrusion of evil. For Just, gothic writers weren’t intending to create ‘realistic’ scenarios, but rather were using the gothic format as a vehicle through which to deal with contemporary issues in a disguised manner, and we see Breton continuing that tradition, as with his own abiding concern with the updating of the culturally resonant motif of the castle.18 I therefore want to ...