![]()

Introduction

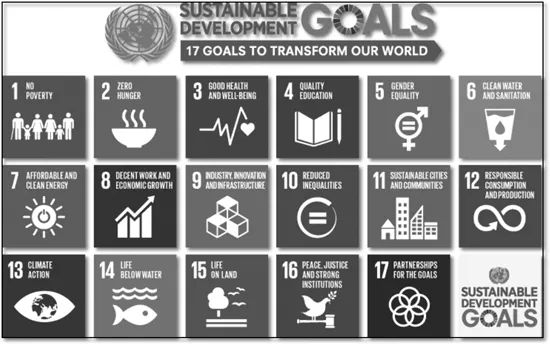

There was both a great fanfare and hopeful exuberance when the United Nations endorsed the millennium development goals (MDGs) on the dawn of the third millennium, and also launched the sustainable development goals (SDGs) in the second decade of the current millennium (UNDP 2003, UNDP 2015). Both the MDGs and SDGs – now also ‘global goals’ – have significant implications for global development, particularly in the case of African countries (Nayyar 2012; Sachs 2012). The SDGs have expanded and specified some of the targets that would shore up African development. In expanding the MDGs, the SDGs incorporate a ‘range of key areas that were not fully covered in the MDGs, such as energy and climate change; and reflect equally the economic, social and environmental dimensions of sustainable development and the interconnections between them’ (UNECA et al. 2015). But the SDGs still tend to overlook varieties of conflict, especially non-traditional security, and the water-energy-food relationship. Unlike the MDGs, the SDGs ‘apply to all nations, developed and developing, bridging governments, civil society, and the private sector to create innovative ways to achieve sustainable development while “leaving no-one behind”’ (Besada et al. 2016: 2) (see figure 1.1).

While some African countries did attain their MDG targets, hence the plausibility of ‘Africa Rising’, the overall state of African development continues to assume attention in the global development discourse (Ayittey 2015; Taylor 2014; United Nations 2015a, 2015b). As Bianchi (2015) points out, while Africa overall registered positive rates of economic growth over the past 15 years or so, thus the claim to ‘African agency’, poverty remains widespread and unemployment is reaching alarming levels (see also ACBF 2016; Beegle et al. 2016; Kharas and Biau 2015). Making the development process sustainable thus represents a key challenge for the future of the continent, and calls for urgent regional and country-specific actions (Bianchi 2015; Hanson 2015). In terms of the general assessment of MDGs and African development, a recurring theme has been the state of institutions, particularly in terms of the discourse of knowledge, regionalism, policy and capacity imperatives; the order of factors is in part a function of which state and what analytic perspective (Hanson 2015; Hanson et al. 2012; Shizha and Abdi 2014; Shizha and Diallo 2015).

In view of the broader concern about Africa’s development agenda, this book addresses two main issues. First, it seeks to interrogate the dynamics between the MDGs and SDGs in key areas of African development; for example, the changing role of the state in sustainable development and democratic governance, agriculture, natural resources management, environmental sustainability and climate change, technology and private sector, and development aid.

Second, it is clear that the extent to which the SDGs will advance the African development agenda will depend on global, continental and regional imperatives. The SDGs have an enhanced and universal aspiration that has to be grounded in global, continental, regional and national realities. The integrated and indivisible nature of the SDGs results from learning from the MDGs. Experience suggests that a solo approach to development yields limited results (Robinson 2017). Consequently, there is an ongoing effort globally, and Africa is no exception, to review development planning visions and strategies, align them with the SDGs, and to carefully set out country priorities. In fact, the SDGs not only ‘underline and underpin the African Union’s (AU) Agenda 2063, “The Africa we Want”, which also calls for a paradigm shift and profound economic and social transformation’ (Besada et al. 2016: 4–5), but also align with the African Development Bank’s (AfDB) High-5s (the Bank’s five strategic priority areas) meant to guide its approach to the continent’s development over the next ten years (AfDB 2015). The five strategic areas are: light up and power Africa; feed Africa; industrialize Africa; integrate Africa; improve the quality of life for the people of Africa. These areas stem from the AfDB’s (2013) Ten-Year Implementation Plan to transform Africa and are also consistent with the AU Agenda 2063.

Indeed, there is synergy between the SDGs and Africa’s ambitious Agenda 2063, including AfDB’s first Ten-Year Implementation Plan. The SDGs line up almost perfectly with the vast majority of the goals of the Ten-Year Implementation Plan, and a detailed look at their respective targets illustrates the strong commonality between the agendas. The integrative potential of the SDGs and the continental initiatives cannot be underestimated, but as Robinson cautions, only ‘through action at the national level, and cooperation internationally, can transformation be achieved’ (2017: xiv).

The requisite action and agency needed to ensure transformation across Africa has been documented by a number of studies (Besada et al. 2016; Bischoff et al. 2016; Brown and Harman 2013) as well as contributors to this volume. Today, African actors can clearly claim a degree of agency rather than endure continuing dependency (Brown and Harman 2013). In areas of transboundary resources management, regionalism (Hanson 2015), security management, and the continent’s engagement with global partners (Bischoff et al. 2016), Africa’s agency is undoubtedly manifest (Besada et al. 2016). The establishment of the Africa Progress Panel (www.africaprogresspanel.org); the Africa Mining Vision (www.africaminingvision.org); or the launch of the Africa Capacity Indicators Report (now Africa Capacity Report) by the African Capacity Building Foundation (www.acbf-pact.org), are all evidence of the growing agency of contemporary Africa (Hanson et al. 2012; Shaw 2015a, 2015b). Elsewhere on the continent, other novel forms of African agency are visible in regional conflict zones such as the Great Lakes, the Horn of Africa and the Sahel, and in the energy and minerals sectors (Besada 2010; Ismail 2014; Shaw 2015a).

The dramatic breakthroughs in communication and information technologies on the economy (the sharing economy) and the transformation of markets and financial transactions (M-Pesa) offer both opportunities and challenges in the development process (Oppong 2015; Saeed and Masakure 2015; Wallis 2016). In the case of the environment and climate change, the water-energy-food security link underlays security concerns, typified by such actors as Boko Haram, Al-Shabaab, and the worsening security environment in countries such as Libya, Somalia, Kenya, Nigeria and Chad (Besada 2010; Kedir 2014; Ismail 2014; and see Ayoyo and Oriola this volume). In the unfolding dynamics, while the state continues to occupy a role, even if a minimal one, the activities of civil society groups including faith-based organizations also deserve attention and analysis especially in terms of democratic governance. For example, in the case of natural resource governance, new forms of overseas development aid and foreign direct investment with the emergence and changing fortunes of China, other BRICS partners, and Taiwan, India, China and Korea (TICKs).The aforementioned all go to reinforce the view that ‘the key to delivering the vision and transforming people’s lives lays in how seriously governments, the United Nations (UN), international organizations, CSOs and business take their roles, together and in partnership, in implementing the SDGs’ (Robinson 2017: xv).

African governments must meet their commitments if they are serious about delivering the promise of Article 10 of the UN’s Declaration on the Right to Development to all their citizens by 2030. To do so, they need to move rapidly beyond rhetoric and political differences to make the right to development a reality for all. The real work to deliver on the right to development is only now starting, thanks to the SDGs, the Paris climate change agreement (CoP 21) and the 2015 Addis Ababa action agenda, which created a global framework for financing development. However, without a renewed commitment and finance, the ground-breaking SDGs will not be met by their target date of 2030, and will remain an empty promise without appropriate political and financial commitment, regulation, management and related safeguards (Dodds et al. 2017; South Centre 2016). The role and significance of an appropriate foreign policy and equally relevant international organization cannot be overemphasized (Warner and Shaw 2017).

While issues such as poverty reduction, gender equality, hunger eradication, hunger, health and education are still very much central to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, there are also some new entries among the SDGs that are particularly salient for Africa (Bianchi 2015). These notables include SDG 16 on peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development; SDG 11 on inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable settlements; and SDG 9 on resilient infrastructure, inclusive and sustainable industrialization, and innovation (see figure 1.1).

In light of this background, this book seeks to assist Africa’s policy-makers and political leaders, multinational corporations and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), plus its increasingly heterogeneous media landscape, to understand and better respond to or negotiate the evolving development environment of the twenty-first century. The book, as alluded above, also crystallizes perspectives and discernments on Africa’s ongoing transition from MDGs to SDGs, drawing on both the wider extant literature as well as nuanced developments taking place at the global and national levels, to provide useful insights into Africa’s agency and drive to attain sustainable development. The next section overviews and justifies our selection of topics and authors which highlight the rationale and sequence of chapters.

Perspectives and discernments

Arthur, in Chapter 2, interrogates the relationship between the African state and development initiatives, arguing that attaining the objectives in development initiatives such as the SDGs in Africa will hinge on good governance. That requires a political environment characterized by transparent, participatory and accountable decision-making processes. The political system should also be grounded in the promotion of the rule of law, anti-corruption mechanisms, participation of civil society in decision-making and effective political leadership.

Next, Ayoyo and Oriola, in Chapter 3, highlight the pertinent issue of conflict and insecurity in Africa, and its implications for continental efforts to transition from MDGs to SDGs. The SDG 11 call for inclusive, safe, resilient communities on sustainable principles means security is integral to the development of any society. The chapter surveys the conflict and insecurity connection on the continent, from Nigeria in West Africa and the consequences for peace in the region, to East African countries such as Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan and Sudan, and North Africa. The chapter contends that the poor performance of many African states during the MDGs era is strongly connected to conflict and insecurity situations on the continent, and cautions that resolving conflicts and security challenges on the African continent would constitute a central issue in achieving the SDGs by 2030.

In Chapter 4, Puplampu and Essegbey examine the policy and institutional aspects of the MDGs situating the performance of African agriculture relative to MDGs 1 and 8. In so doing, they help to contextualize the extent to which the SDGs, as a follow-up program, are able to attain desirable policy and institutional outcomes in the agricultural sector, a vital aspect of Africa’s development agenda. Central to the chapter, is the focus on threats and pitfalls in implementing global, continental, regional or national policies as well as the institutional imperatives for desirable outcomes in agriculture. The chapter submits that underpinning agricultural policy and institutional performance are problems linked to the availability and access to resources.

While the previous chapters looked at broader policy and institutional issues, Odoom, in Chapter 5, shifts the attention to the rapidly growing and contentious role of China’s development cooperation practices in Africa. The chapter undertakes a comparative analysis of the traditional and contemporary sources of development assistance, placing the analysis in a relevant historical context. Demonstrating Chinese development assistance in several African countries...