![]()

1China’s hydropower development in Africa and Asia

Implications for resource access and development

Giuseppina Siciliano and Frauke Urban

Chinese hydropower development goes global

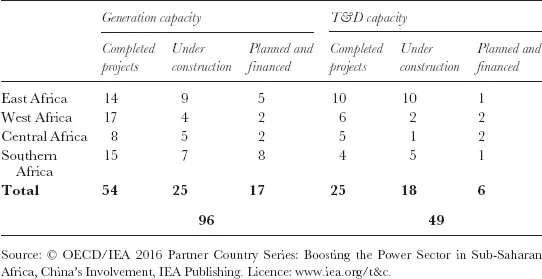

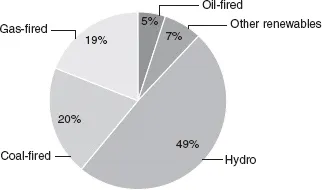

Large dams have been controversially debated for several decades due to their large-scale and often irreversible social and environmental impacts (WCD, 2000). In the pursuit of low-carbon energy and climate change mitigation, as well as improved energy access in energy-poor countries, hydropower is experiencing a new renaissance in many parts of the world, especially in Africa and Asia, despite its vulnerability to climate change (IPCC, 2011). Worldwide, almost four billion people lack access to modern energy services, such as electricity or cleaner forms of cooking, and the majority of them are located in the global South (IEA, 2015). The low rate of electrification in many countries in the global South today, especially in Africa and Asia, has been identified as one of the most pressing obstacles to economic growth and poverty alleviation (IEA, 2015). Full electrification requires increased investments in these regions, including small-, medium- and large-scale on-grid and off-grid electricity generation capacity and networks. China has been identified as the leading global investor in energy infrastructure, particularly renewable energy, in the global South (IISD, 2016). Chinese companies operating as the main contractor were responsible for 30 per cent of new capacity additions in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2010–15. Between 2010 and 2020 total additions will be equivalent to 10 per cent of existing energy capacity (Table 1.1). Projects by Chinese companies cover almost the entire electricity mix, dominated by hydropower. Renewable sources account for 56 per cent of total capacity added by Chinese overseas projects between 2010 and 2020, including 49 per cent from hydropower (Figure 1.1).

Table 1.1 Overview of Chinese power projects in Sub-Saharan Africa, 2010–20

Figure 1.1 Chinese-added generation capacity mix in Sub-Saharan Africa, 2010–20.

Source: © OECD/IEA 2016 Partner Country Series: Boosting the Power Sector in Sub-Saharan Africa, China’s Involvement, IEA Publishing. Licence: www.iea.org/t&c.

Similarly, Chinese projects in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ (ASEAN) power sector have increased significantly over the last decade, with China emerging as the dominant financier of hydropower projects in the region (IEA, 2016). In the period 2006–2011, Chinese investors financed 2,729 MW of hydroelectric capacity additions in Southeast Asia and 46 per cent of the new hydroelectric capacity in Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar (EIA, 2013).

Currently, Chinese actors are the world’s largest dam builders. Sinohydro, a Chinese state-owned enterprise (SOE), is leading the global hydropower sector in terms of number and size of dams built, investment sums and global coverage. While China has a long history of domestic dam-building, recent developments have led to Chinese overseas investments, particularly in low- and middle-income countries in Asia and Africa (Bosshard, 2009; McDonald et al., 2009; International Rivers, 2012). China’s engagement in overseas dam-building is part of the Chinese ‘going-out’ strategy, which was incorporated for the first time in the 2001–5 tenth Five-Year Plan. In addition, Chinese overseas involvement is encouraged under the ‘One Belt, One Road’ initiative launched by President Xi Jinping in 2014 (Clover and Hornby, 2014). This initiative aims to support the internationalization of Chinese companies and the government’s ‘going-out’ strategy (IEA, 2016). Previous studies have highlighted as the main drivers of Chinese investments in Africa and Asia the desire to access new markets in the power sector, as well as natural resources (Urban et al., 2011; Bosshard, 2009; Mohan, 2008, Alden et al., 2008). The current economic slowdown in China and overcapacity in various sectors is compelling Chinese companies to search for new markets overseas. Over 90 per cent of Chinese-built power projects in Africa, for instance, are contracted by Chinese SOEs. Africa is therefore the largest overseas market for some major Chinese SOEs’ energy infrastructures, which provide integrated services centred on turnkey projects (IEA, 2016). Moreover, China’s rapid economic growth has depleted scarce domestic natural resources; its ‘going-out’ strategy therefore encourages overseas investments to access natural resources (Mohan and Power 2008, McNally et al., 2009). For example, China’s investment capital is expected to create more than 2,000 MW of electricity capacity in Laos. Added capacity has turned Laos into a major regional exporter of electricity, especially electricity generated from hydropower, much of which goes to China (EIA, 2013). Similarly, a trade agreement based on cocoa resources has been attached to the Bui Dam in Ghana, the largest Chinese-funded project and the largest foreign investment after the Akosombo Hydroelectric Power Project in the country, jointly funded by the Government of Ghana and the Chinese Exim Bank via a commercial loan and buyer’s credit, as well as the Government of China via a concessional loan. For repayment of the loans, there is a trade agreement between China and Ghana, in which Ghana is paying back the loans to China’s Exim Bank with revenues derived from cocoa production (Dwinger, 2010; Odoom, 2015). This means the bundling of trade, aid and investment has happened for the Bui Dam deal. China’s engagement in energy infrastructure in Ghana therefore has a complex dynamic, given its dual role as financier and builder of energy infrastructure, and at the same time China’s interest for Ghana’s natural resources.

In terms of global coverage, there are currently more than 333 Chinese overseas dams, most of them in Southeast Asia (38 per cent) and Africa (26 per cent). The majority of these are large dams that have been built after 2000 (International Rivers, 2013), in a time when other dam-building nations and organisations, particularly those from the OECD, had withdrawn from the dam-building industry. Compared to other OECD investors in hydropower, Chinese dam-builders differ due to their bundling of aid, trade and investments; the role of SOEs that are backed by abundant state funding; their own distinctive way of handling (and not seldom disregarding) social and environmental impacts; their pragmatic approach to regional politics and political alliances and their need for access to natural resources (Urban et al., 2013a, 2013b; Hensengerth, 2013; see also Tan-Mullins and Mohan, 2013).

In this context, the primary aim of this book is to shed new light on China as a rising power in low-carbon development, specifically hydropower, in Asia and Africa, from a sustainable development perspective comprising the political, economic, social and environmental aspects. The book draws mainly from contributions of scholars and experts of Chinese hydropower development in the global South and locally based authors using extensive field interviews, focus group discussions, document analysis and participatory workshops with relevant stakeholders and local communities affected by Chinese hydropower projects in Africa and Asia. The book is divided in two main parts: the first part deals primarily with general aspects of Chinese involvement in hydropower development in Africa and Asia from a political and economic perspective (Chapters 1–5). The book then presents selected case studies from large dams built and financed by Chinese actors in Asia and Africa, namely the Kamchay Dam in Cambodia, the Bakun Dam in Malaysia, the Bui Dam in Ghana and the Zamfara Dam in Nigeria to illustrate from a political economy, political ecology and Asian Drivers’ perspectives how divergence between builders and national priorities of energy production on one side and local development needs on the other side can result in the unequal distribution and conflicts over access to resources, such as water, land and forest (Chapters 6–9). The case studies are part of a four-year research project entitled ‘China goes global: a comparative study of Chinese hydropower dams in Africa and Asia’, funded by the UK Economic and Social Research Council ESRC (reference ES/J01320X/1).

This chapter first provides an overview of the extent to which Chinese builders and financiers are involved in large hydropower projects all over the world, and specifically in Africa and Asia. The ch...