Introduction

When colonialists arrived on Rapa Nui around AD 1100–1300 (Hunt and Lipo 2006; Wilmshurst et al. 2011; Mulrooney 2013) their double-hulled canoes were loaded with the plants and animals necessary to start a new life on a remote volcanic island. This pristine habitat mostly covered by a dense palm forest (Mieth and Bork 2005) and an understory of about a dozen shrubby species (Orliac 2000) was the home to nesting sea birds and possibly a small rail (Steadman et al. 1994). While this diminished biodiversity might have worried the Polynesians arriving during the initial discovery voyage, it was not sufficient to deter a later colonization effort. What could not be assessed at that time was the full range of ecological and geological constraints, the eventual human-generated environmental challenges, and technological changes that would eventually impact the Rapa Nui farmers in the years to come.

Recent research into prehistoric agriculture on Rapa Nui has demonstrated that its small size, low elevation, wind-driven evapotranspiration, cool temperatures, and lower rainfall restricted these farmers to dryland agriculture (Horrocks and Wozniak 2008; Stevenson et al. 2006; Wozniak 1999) and small-scale irrigation by rain-water capture techniques (Stevenson 1997). During the first few centuries of settlement, the surface vegetation may have served to buffer environmental stresses but with the rapid slash-and-burn process of deforestation that cleared the lower elevations of Rapa Nui by AD 1450 and the upper elevations by the early AD 1600s (Horrocks et al. 2015), the damage to agricultural productivity must have been soon recognized. In the face of this self-inflicted change in environmental conditions, the Rapa responded technologically by creating rock gardens and behaviourally by more direct supervision and management of agricultural production (Stevenson et al. 2005).

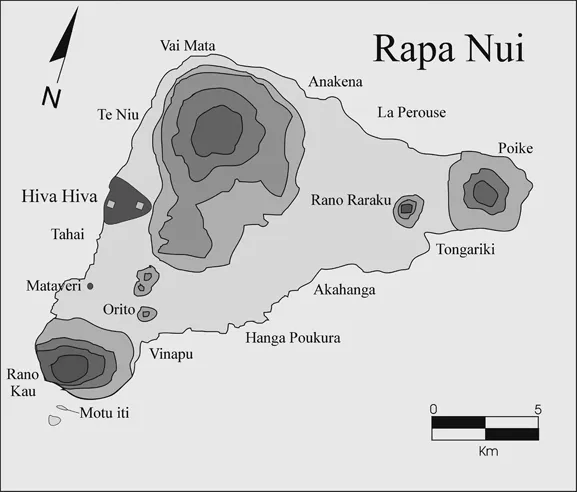

The Hiva Hiva lava flow (Figure 1.1) is one such place on Rapa Nui where pre- and post-deforestation agriculture would have been practiced. This geological substrate represents the most recent volcanic activity on Rapa Nui and its emplacement is dated to approximately 0.11 mya (Vezzolli and Acocella 2009). The recent age of the flow, in comparison to the more extensive and older lava sheets (0.78–0.3mya) covering the remainder of Rapa Nui, means that the newly created ground surface has experienced much less weathering and rainfall leaching. As a result, the surface has the appearance of basalt rock outcrops covered by thin soils in convex positions that are interspersed with accumulated tephra-and/or volcanic loess-based soils in swales. These factors suggest that human use of the landscape would have required adaptations to a unique set of circumstances not found in many other parts of the island.

Figure 1.1 Island of Rapa Nui showing the location of Hiva Hiva

Archaeological survey and remote sensing within the last decade (Stevenson and Haoa 2008; Ladefoged et al. 2012) has identified the numerous rock gardens that cover much of the Rapa Nui landscape. These gardens consist of a variety of stone accumulations that can be characterized as boulder, veneer, or lithic mulch gardens (Stevenson et al. 1999). The Hiva Hiva terrain is covered by numerous prehistoric rock gardens. It is also well suited for farming on a treeless and windy terrain because the ground surface is undulating and has many swales and protected areas created by elevated lava exposures. In addition, the large quantity of basalt surface rock provides ample raw material for the construction of rock gardens and walled enclosures.

The success of ancient farming also depended upon the quality of the soil. In many other parts of Rapa Nui the soils have been characterized as nutrient poor (Louwagie et al. 2006; Ladefoged et al. 2005; Vitousek et al. 2014) as reflected by low levels of available plant phosphorus (P). This is clearly the situation at higher elevations on Maunga Teravaka (300m+) where orographic generated rainfall over hundreds of thousands of years have resulted in excessively leached soil nutrient profiles (Stevenson et al. 2015). On more recent substrates such as Hiva Hiva, we would expect the soils to be more nutrient rich, but it is also possible that available nutrient levels are limited since mineral weathering of the substrate has not been extensive (Lincoln et al. 2014). A second possibility is that soils in the swales could be composed of eroded material that has been re-deposited by wind. A third possibility is that the soils overlie older volcanics below the Hiva Hiva flows and could have been incorporated into less fertile in situ soils through farming.

In this work we present the results of systematic pedestrian field survey within the Hiva Hiva flow which has documented the rock gardens and stone domestic features that cover the landscape. We use soil chemical analyses to assess the nutrient status of gardens, their formation processes, and the strategies of enrichment. Radiocarbon dating and obsidian hydration dating is used to track the intensity and duration of landscape use.

Archaeological investigation of Hiva Hiva

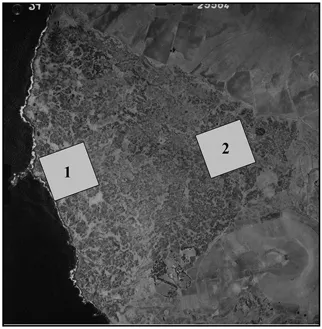

A comprehensive archaeological survey of Quadrangle 15, which contains the Hiva Hiva lava flow, was completed in 2007 and the effort recorded over 2200 cultural features (Haoa n.d.). These data were integrated into a comprehensive GIS data base. From this large data set, we selected cultural features within two 500m × 500m survey areas as a sample of the larger flow. Survey Area 1 was placed near the west coast and Survey Area 2 was located inland near the eastern margin of the flow which contained the cinder cone named Hiva Hiva (Figure 1.1; Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 The Hiva Hiva lava flow showing the location of Survey Areas 1 and 2

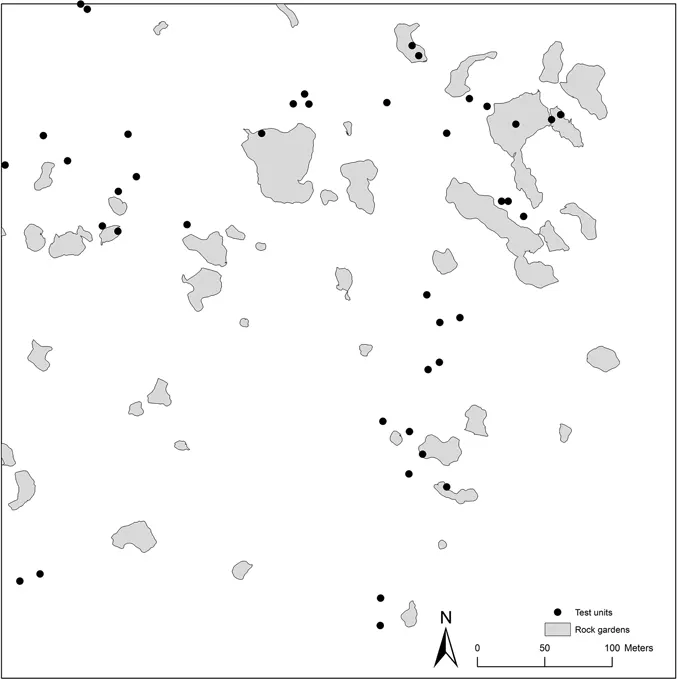

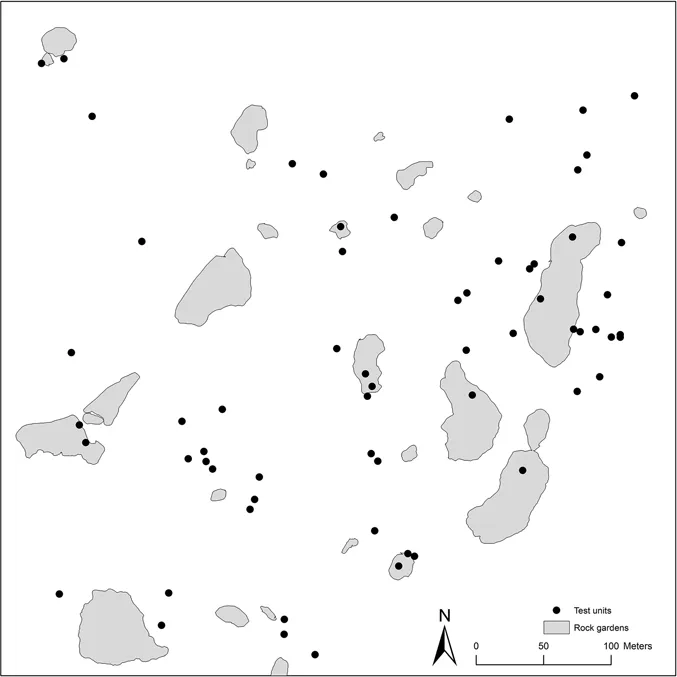

The objective of the field investigation was to re-survey the two sample areas at an intensive level to record the distribution and boundaries of the prehistoric rock gardens not captured in the original survey. Once identified and mapped with GPS, a sample of the gardens were tested with 50cm2 shovel tests to confirm if an anthropogenic soil, or Ap-horizon, was present beneath the surface rock layer. Obsidian artefacts and charcoal samples were recovered when present. Soil samples were also taken for a nutrient assessment of garden fertility. Approximately 150 grams of earth were recovered from the shovel test profiles at a depth of 20–25 cm. Shovel tests were also placed outside of gardens to obtain soil samples from equivalent depths in non-cultivated contexts. A total of 38 gardens and 31 non-gardens were tested (Figure 1.3).

Each previously recorded cultural feature was relocated using GIS maps and a list of UTM coordinates. These features included above ground structural remains such as houses and alignments, as well as modified natural

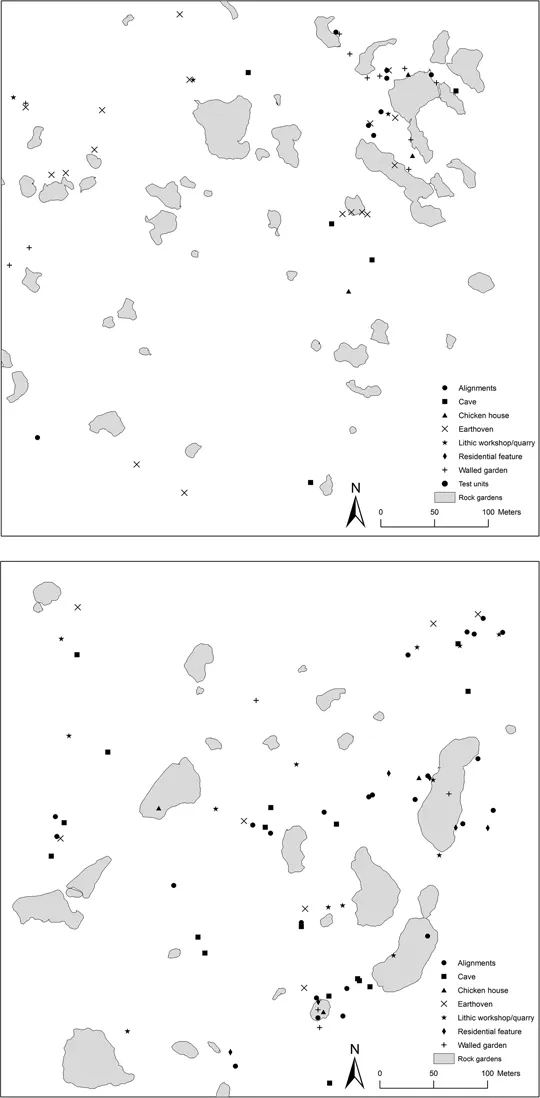

Figure 1.3 Garden and test unit locations for Survey Area 1 (top) and Survey Area 2 (bottom)

features such as caves. Shovel testing was also conducted adjacent to these remains to assess the depth of deposits and to recover obsidian and carbon for chronometric dating. A total of 251 sites were relocated and 70 were tested (Figure 1.3; Figure 1.4).

Prehistoric landscape settlement

Survey area 1

The terrain in Survey Area 1 consists of low hills and ridges separated by small valleys that gradually decline in elevation from East to West. Archaeological surface remains are numerous and a total of 91 features were documented in the initial survey (Haoa n.d.). The major categories of features included beach

Figure 1.4 Feature locations in Survey Area 1 (top) and Survey Area 2 (bottom)

cobbles (poro), stone mounds, stone walls, lithic workshops, walled gardens (manavai), and worked stone (paenga). Prehistoric settlement remains were not evenly distributed and formed clusters of features in the northwest, northeast, and southeast quadrants of the survey area (Figure 1.4). The regions between the clusters exhibit few indications of prehistoric settlement.

The northwest cluster contains two domestic habitation areas defined by beach cobbles and a pavement that are indicative of former houses. Two walled gardens are near the houses, and stone walls and small stone mounds are located at the periphery of the cluster and near the adjacent rock gardens. These are likely agricultural windbreaks located within or at the margins of gardens. A single basalt stone quarry for the production of garden boulders was also present.

The northeast cluster consists of numerous surface features within a large garden complex (Figure 1.4). Amidst the gardens is an association of domestic features that suggests a permanent settlement. These features consist of a large chicken house (hare moa), a house pavement, an activity area defined by core-filled walls (muro vakaure), numerous walled gardens, and various low stone mounds. These domestic features and the associated gardens suggest that the feature cluster represents an agricultural hamlet.

The southeast cluster exhibits a different association of stone surface features. Several beach cobbles suggest that a dwelling was once present. Positioned close to them were a set of four low-density obsidian workshops and a water hole. On the eastern edge of the cluster five caves, a water hole, and a basalt stone quarry were spatially associated. Gardens were few in this part of the survey area and indicate that farming may not have been the primary activity. Obsidian reduction for flake tools may have been the principal task.

Survey area 2

The central terrain feature of Survey Area 2 is the volcanic cinder cone called Hiva Hiva. The cone is approximately 40 m high and occupies about a third of the survey area. On top of, and surrounding the cone, are 160 cultural features. At the summit of the cone are a set of two large depressions created to extract basalt blocks that were modified into finished rectangular blocks (paenga) which served as building materials for religious platforms (ahu) or elite houses. Large exposures of basalt in this area were also exploited for suitable raw material and numerous unfinished blocks surround the cone at the base (Figure 1.4). Also located on top of the cinder cone, but at a lower elevation to the east, is a tight clustering of features that forms a well-defined living area. A level living terrace contains an alignment of worked stone, inferred to represent a substantial house. It overlooks a collapsed lava bubble that has been converted into a rock garden that is 30m in diameter. At the margin of the garden were an activity terrace, a small cave, a water hole, and two additional walled gardens. A shovel test placed on the activity terrace revealed that the surface was formed by compacted basalt particles 1–2 mm in diameter. These particles were the byproducts of paenga manufacture and were likely imported from the nearby quarry. This physical link suggests that the quarry labourers probably resided at this location.

Additional habitation sites defined by beach cobble pavements surrounded the base of the cinder cone and are associated with the numerous gardens in this area. On the south side of the cinder cone, a well-articulated elite house is present and other isolated worked stones (paenga) indicate that additional houses of this type may have once been in the area. This suggests that an elite managerial presence was associated with the quarrying activity on top of the Hiva Hiva cinder cone.

The northeast portion of the survey block contains two areas of intensive occupation. The first is located around the margin of a very large rock garden contained within a collapsed lava tube. House pavements, an elite house, stone alignments, obsidian concentrations, a chicken house, and stone walls overlook the garden that is located 10m below. This rock garden and the others in the immediate area, in all likelihood, helped support the quarry labourers and elite managers at Hiva Hiva. The second area is positioned immediately north of the garden and consists of an elite house associated with obsidian lithic scatters or workshops, a cave with an image of the Birdman on the exterior, and numerous water holes. Adjacent household gardens were absent from this cluster of surface features

The distribution of geological features, rock gardens, and surface cultural remains on the Hiva Hiva landscape reflect distinct types of activity ...