![]()

Part I

Exhibiting Women

Collectors, Artists and Students

![]()

1 Expositions and Collections

Women Art Collectors and Patrons in the Age of the Great Expositions

Julie Verlaine

Introduction

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, visiting a world exposition was an unforgettable experience for many Western women, thanks to the spectacular pavilions, exhibits and performances on show. The sense of wonder that is conveyed in most press reports of the time (illustrated or not)1 can also be found in the letters, diaries or memoirs of women who recounted these memorable experiences.2 For a few such women, these events represented far more than entertainment or discovery, they constituted a turning point in their lives: fair-going encouraged them to begin or to expand their own personal collection of artworks and objets d’art.

Most major women art collectors from the period 1870–1940 left archives that offer precious insights into the social practice of collecting, defined as an activity where each individual builds his or her own view of the intelligible world. Indeed, collecting involves both a material and an intellectual dimension, combining the abstract sphere of desire and self-representation with the concrete sphere of purchasing and owning. Despite their low visibility—and even their “silencing”—in general histories of Western art, women art collectors were numerous and shared certain socio-cultural traits from the mid-nineteenth century on. These traits included a high level of affluence that enabled them to travel and make purchases, to have greater autonomy than ordinary women of their time, thanks to inheritance or widowhood, and experience integration into social networks at the local, national and international levels.3 Research in their archives brings to light the role the major world expositions played in these women’s itineraries. Almost all American women art collectors visited the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, the Chicago Columbian Exposition or the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, and most of them (as well as their European counterparts) visited the Universal Expositions in Paris in 1889 and in 1900, or that of Brussels in 1910. This period coincided with a slow but profound transformation in women’s collecting. While collecting practices remained strongly focused on the domestic sphere—decorating the home remained the main motive for women to acquire works of art and other precious objects—increasingly their collections had repercussions in civil society. Mrs. John O’Connor, president of the Chicago Woman’s Club, stated in 1910: “The home is the center of life, and if we can take art into the homes and then through the homes into the neighborhood, and then from one neighborhood into another, we shall soon make our own city beautiful.”4 There was a growing capillarity between the domestic and public spheres, and the world expositions represented a critical venue for women to enter the public sphere.

This chapter addresses the relationship between expositions and the gradual transformation in women’s positions on the artistic scene. From mere spectators and “consumers” of art, Western women increasingly became organizers and active supporters of artists, including many women artists, of their era. Expositions acted as catalysts, or privileged opportunities, in the evolution of women collectors’ practices (which became increasingly active) and their status (which gained in visibility). Thus, I begin by looking at the link between these major expositions and the awakening of women’s interest in becoming collectors or patrons of modern art. Then I will focus on how, by visiting the expositions, women were encouraged to collect art and to expand their collecting horizons. Finally, the article addresses how participation in these expositions could also spark political awareness in support of women artists and women’s rights, and, in some cases, encourage women to become activists.

Visiting World Expositions, Acquiring a Taste for Art Collecting

At mid-nineteenth century, and especially during the 1862 London Exposition and the Centennial Exposition of Philadelphia in 1876, millions of Western visitors discovered a wealth of tapestries, furniture, ceramics, glassware and other art objects. International expositions as well as fairs dedicated to the products of art and industry did not directly contribute to a legitimization of the decorative arts and objets d’art, but they facilitated the appreciation of these works by large numbers of male and female visitors.5

Enthusiasm for collecting was widespread between 1860 and 1890, touching both men and women, from England, Europe or the New World. The number of women art collectors grew constantly—albeit never outnumbering the number of men. As the number of collectors grew, their sociological background also broadened. Art collecting went from being a practice of the aristocracy and courtiers in the eighteenth century to involving the upper and middle bourgeoisie of industrial cities. In Britain, a few women achieved recognition both as art collectors and art experts, including Lady Charlotte Schreiber, Lady Dorothy Nevill and Mrs. Fanny Palliser. For these women, expositions provided access to the latest artistic creations and allowed them to expand their own collections. In her diary, published posthumously by her son as Confidences of a Collector of Ceramics and Antiques throughout Britain, France, Holland, Belgium, Spain, Portugal, Turkey, Austria and Germany from the year 1869–1885, Charlotte Schreiber records the details of her continual “hunt” (she uses the French term chasse) for new ceramics, and the treasures she found notably in Paris (International Exposition of 1867) and Cologne (1876 Art Exposition).6 In 1874, after collecting ceramics and antique lace for three decades, Fanny Palliser wrote and published The China Collector’s Pocket Companion, a pocket guide to all the marks, back stamps and signatures of Western pottery and ceramic makers.7

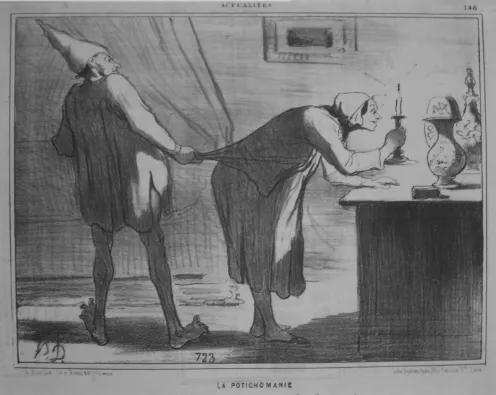

Some upper-class women from Britain and the United States collected decorative objects with such frenzy that critics (mainly men) began to describe their activity as “Chinamania,” “bric-a-brac mania” or “potichomania.” Charlotte Schreiber herself spoke of her own collector’s “rage.” The caricaturist Honoré Daumier mocked what he described as “Potichomanie” (potichomania) in the satiric magazine Le Charivari in January and February 1855 presenting the collection of decorative objects as a female activity. The series highlights how representations of female collecting reflected a range of misogynistic prejudices as well as gendered assumptions about women’s roles (see Figure 1.1). To begin with, it was more acceptable for a woman to acquire objects for the home than for her own enjoyment; hence it was tolerated if she combined a useful pastime with an enjoyable one. As the woman’s domain was reduced to the domestic sphere, the tasks of a mistress of the house included furnishing and decorating. Several treatises on domestic economy, such as Catharine Beecher’s A Treatise on Domestic Economy, published in the U.S. in 1841, emphasized that the choice of a decorative object must be subordinate to the overall arrangement of the home. The delicacy of domestic objects, such as porcelains and ceramics, reinforced the association with femininity. The small size and refinement of these objects were seen to reflect the delicacy of women themselves, thus diffusing a feminine ideal. In the popular imagination, however, a whole range of negative connotations rounded out the overall picture: women’s invasive infatuation with baubles was seen as a form of addiction. Pushed to the extreme, this behavior could lead to extravagance and obsession, threatening the family with financial ruin or turning maternal affection away from the children. Among men, this addiction was the sign of sexual inversion, a form of femininity regarded at the time as a dangerous illness.8

Figure 1.1 Honoré Daumier, La Potichomanie—Voyons, Adélaïde, voyons, sois raisonnable, il est temps de se coucher, il est une heure du matin!—Adolphe … laisse-moi contempler mon ouvrage, c’est encore cent fois plus joli à la chandelle! . . . (Say there, Adelaïde, be reasonable, it’s time to go to bed, it’s 1:00 in the morning!—Adolphe … let me contemplate the image, it’s one hundred times more beautiful by candlelight! …) Lithograph, Honolulu Museum of Art, accession 13511, public domain. Digitalized by Wikimedia Commons.

The disparaging of women’s collecting practices was not limited to the French. Both in Europe and North America, collecting carried strong gendered connotations. “Real” collectors had an ability to discern the conceptual and visual variety within a set of objects, a trait that was considered to be exclusively masculine. In the United States, Sarah Poulterer Harrison (1817–1906) assembled a large collection of decorative objects. Her acquisitions, however, while important in terms of quantity and quality, were not deemed to be a collection but rather a form of consumption. With her husband Joseph Harrison, Jr., an engineer who made his fortune designing locomotives, she enjoyed the privileges of wealth in Philadelphia during the 1860s. Together they did much to promote the arts and industry. During the Great Central Fair for the U.S. Sanitary Commission, in 1864, Joseph Harrison was chairman of the Fine Arts Committee, while his wife was a member of seven different committees, including Fine Arts, House Furnishing Goods, and the rather eclectic “Fancy Goods, Watches, Jewelry, Silver and Plated Ware.”9 Widowed in 1874, Mrs. Harrison inherited an immense fortune, which she used during the 1876 Centennial Exposition to acquire many artworks and especially objets d’art. Tellingly, the precise list of these acquisitions has been lost, contrary to the eleven history paintings that she bequeathed, upon her death, to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in memory of her husband, Joseph Harrison, Jr.10

Disdain for women’s artistic taste was widely shared during the Gilded Age in the United States and reflected in the inventories of the period. For example, Quaker art critic Earl Shinn profiled few women in his three volume Art Treasures of America published between 1879 and 1882 after visiting 200 private collections.11 While mentioning that women were increasingly responsible for contemporary interest in modern art, Shinn only cited twenty-two collections owned by women. Nearly all of these women were widows or heiresses; he presented them as the custodians of the collections of their late husbands or fathers. Shinn recognized only a handful of women as major donors and patrons of the arts, for example, Catharine Lorillard Wolfe of New York City, Alice Surgis Hooper of Boston, and Jane Stanford of San Francisco. The other women collectors received scant attention in part because the objects they collected did not belong to the fine arts (painting, sculpture) but to the purportedly “minor” decorative arts (ceramics, textiles, jewelry, furniture).

Within Shinn’s publication, like in other European publications of the same era,12 the ideal collector bore no resemblance to the frenzied representation of a wealthy woman who succumbed to “potichomania” or “bric-à-brac mania.” The ideal collector was a philanthropist a...