![]()

1

Introduction

Rudi Turksema, Peter van der Knaap, and Steffen Bohni Nielsen

Evaluation and Success

“Real change will come when politicians see evidence and evaluation as ways of helping them entrench policies” (Rutter 2012, 5).

The idea for this book surfaced from a general notion that evaluation in the public sector—despite all of its potential benefits (e.g., Leeuw 2010) and despite its professionalization and institutionalization in the past fifty years—does not fulfill the role most of us have in mind for evaluation and performance auditing. Evaluation’s main potential contribution is in the areas of accountability (transparency) and organizational learning (better policy making), two areas that are in themselves most relevant, but also at tension with each other (Stern 2003). We also observe that the intended users of evaluations—politicians and policy makers—do not always welcome the outcome of evaluations, as they quite often show that policies seldom work and focus mainly on errors, mistakes, and shortcomings. This might in itself be a correct conclusion, but it might not help bring about better policies or policy delivery if the end users ignore the results. Critics therefore argue that evaluation only plays a marginal role in both organizational and policy processes and decision-making:

“There is a common, underlying problem of information use in trying to get people to use seat belts, stop smoking, exercise, eat properly, and pay attention to evaluation findings” (Patton 2008, 13).

“Evaluation use is arguably now the most studied area of evaluation” (Fleischer and Christie 2009).

Weiss, questioning the purpose of evaluation—“Is anybody there? Does anybody care?”—summarizes the problem of utilization as follows: “Evaluation enters ‘a policy community,’ a set of interacting groups and institutions that push and haul their way to decisions through what Lynn (1987, 269) calls “fluid, overlapping, and ambiguous processes.” To gain influence, the ideas have to come into currency and be accepted in ongoing program and policy discussions. More often than not, however, evaluation findings seem irrelevant to the needs of the policy maker: “Even the best and greatest evaluations only minimally affect how decisions get made” (Weiss, cited in Alkin (1990, 43).

People increasingly question the contribution of evaluation work. Are the findings being used? Is it relevant and not mainly an administrative burden? Does it really contribute to better performance? As a result of this, evaluation is—and perhaps increasingly—associated with failure rather than with success (e.g., The Audit Society by Michael Power).

The use of evaluation is a widely studied topic. We won’t do that all over again in this book. Interested readers can find much information on types of use and factors contributing to use in the recent book of Läubli-Loud and Mayne (2013), and somewhat less recent but still excellent work from Weiss (1998) and Patton (2008). Rather, in this book we focus on the mechanisms underlying and contexts influencing use. Before we go into that, we’ll first briefly describe how two generations of evaluation have sought to improve the use of evaluation work, as this is, of course, not novel ground.

Where Do We Come From?

Several authors (e.g., Abma 1996; Dryzek 1982; Fischer and Forester 1993; Guba and Lincoln 1989; Majone 1989; and Schwandt 2001) have suggested that this lack of use can be explained by how we evaluate. According to such authors, policy making is not discrete, but pluralist and interdependent by nature. Therefore, the focus of traditional evaluations on the rational-objectivist model of policy evaluation is wrong. Instead, an argumentative-responsive approach is forwarded, in which the attention shifts to the recipients and other stakeholders of evaluation (a.k.a. participatory evaluation approaches).

“First, the development and implementation of policies requires the support, participation, or even cooperation of many actors. Second, the complexity of modern society’s problems appears to be increasing every year. No longer can policy measures be rationalized by means of a stern, efficient, and rational governmental center, that, on the basis of sophisticated research, allocates binding values and norms with authority (In ‘t Veld 1989). In sum: Central to the argumentative-responsive approach is the belief that, through constructive argumentation, policy actors, networks, or advocacy coalitions may arrive at better judgments on policy issues and, hopefully, at better policies and ways of delivering those policies (Van der Knaap 2006).

Other authors (e.g., Leeuw 2008) argue that the lack of use has to be explained by the fact that evaluations are not substantive enough. The quality of many evaluations, in terms of design and execution, too often hampers the quality of the outcomes of evaluations, and thus deliver too little evidence. The “evidence movement” has therefore advocated that evaluations should conform to the “golden standard” in evaluation, in order to lead to robust and reliable evidence. This, in turn, should lead to more use and better informed policy making. There is, however, also a considerable downside to evidence-based policy making: “When we have burning questions we can’t sit there and wait thirty years to get the next randomized trial” (Rutter 2012, 8).

This Book: A Different Angle

The aforementioned issues on the supply side of evaluation are obviously important to the use of evaluation results in policy making. The clarity of an evaluation design, a flawless process in which all relevant stakeholders are involved, and the training and experience of people carrying out the evaluation study and the quality of evaluation reporting all matter a great deal. Quality does matter. It would be a mistake not to stress the importance of clear designs, professional evaluators, or high-quality reporting for anybody who wants evaluations to make a difference and who seeks to learn from evaluations. In fact, this book provides many different lessons to improve evaluation design, processes, and reporting. However, despite all of the improvements in the past years in how we evaluate, it appears that evaluations still are not used enough, and that evidence-based policy making has not gained momentum (Mayne 2009; Pollitt 2006; Rutter 2012). We see two explanations for this.

First, we think that—next to the aforementioned issues (how we evaluate)—there is also something to be improved in what we evaluate, in order for it to be successful. While a great deal of evaluative work focuses on failure in evaluation (what does not work), focusing on success (what works) might be a necessary ingredient for more successful evaluations (in terms of use). We know from psychology (e.g., B. F. Skinner’s work) and neuroscience that we may learn more from success than from failure. Recent research by MIT’s Picower Institute for Learning and Memory indicates that—at the neural level—we process information more effectively after a success than after a failure (Histed, Pasupathy, and Miller 2009; Joelving 2009). Brain cells apparently keep track of whether behavior was successful or not, so it is at a very deep cognitive level that we learn more from success than from failure. We also feel that evaluation (and audit) can be put to a more effective and rewarding use if it would focus on success rather than on failure. This idea is strengthened by recent developments in evaluation approaches, such as appreciative inquiry, but also the development of approaches like participatory evaluation and empowerment evaluation. Moreover, managers apparently do not know how to learn from failure, as it is mainly perceived as something bad and not something to learn from (Edmonson 2011).

So, from a psychological perspective, tremendous benefit may be derived from the insight that a positive stance toward feedback information and evaluation can be a motivational factor of tremendous force. This is reflected in many of the chapters of this book. Its main concepts are positive thinking, time for real learning (both within and between organizations), paying due attention to conceptualization, internalization, transformation, and ownership. The combination of a positive angle and putting “understanding-needs” central to the evaluation allows for the development—within the frame of each evaluative enquiry and context—of an intentional learning strategy. It connects to the cognitive schemes and levels of learning as described above.

Second, the use of evaluations is a matter of supply and demand. If there is no demand (by actual decision-makers, not to be mixed up with the people involved as a stakeholder) for high-quality, evidence-based, and very responsive evaluations, we might be barking up the wrong tree. This issue has been addressed before in Can Governments Learn? (Leeuw, Rist and Sonnichsen 1994), an earlier volume in this series. In a recent report from the Institute for Government in the United Kingdom, Jill Rutter (2012) suggests that most barriers are indeed on the demand side. According to Rutter, “Both incentives and culture (on the side of ministers and civil servants) militate against more rigorous use of evidence and evaluation.”

The interaction of focusing on success rather than failure and the recognition that there should be an actual demand for evaluative knowledge is the central topic of this book. In this book we try to connect these concepts. The connection between the positive approach and organizational learning is especially interesting: Does focusing on what works lead to better organizational learning and thus more success/more successful organizations? The contribution of this book will be in providing both a theoretical framework and empirical examples of what it is in evaluative inquiry and organizational learning that contributes to success/successful organizations. Two questions are therefore central to this book:

1. Why should focusing on success in evaluation lead to more success?

2. Which aspects of evaluation lead to more success?

We are interested in how successful organizations learn from and use evaluative processes and information. Which characteristics do these organizations and their evaluations have that lead them to take maximal advantage of evaluations? Cases will be drawn from public, private, and not-for-profit organizations. Comparative analysis of the case studies will identify factors associated with successful learning systems. This exploratory work will help to verify, and hopefully improve, existing conceptual frameworks.

Conceptual Framework

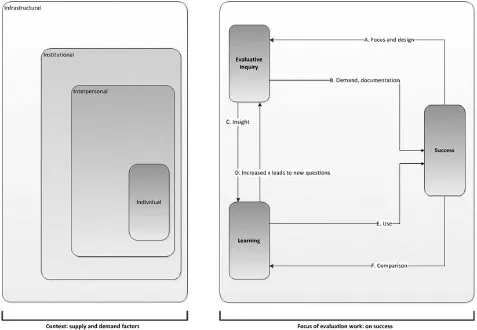

The following figure contains the concepts that are central to this book: evaluative inquiry, organizational learning, and success.

The first central notion (Success ↔ Evaluative Inquiry) is that a positive evaluation works. An orientation on success and success factors will contribute to highly effective learning processes in organizations and policy systems. It explores several assumptions, such as:

• Positive evaluation inspires learning

• Learning leads to success

• Success (high performance, positive results) will drive future evaluation

In addition to taking an orientation toward success as a starting point, the second notion of the book (Evaluative Inquiry ↔ Organizational Learning) is that by investing structurally in high-quality evaluation, evaluators can factually “scheme” learning processes in organizations and policy systems.

Figure 1.1. Conceptual Framework.

Here, evaluation leads the triggering of learning processes. Investing in (the quality of) evaluative inquiry to improve organizational and policy-oriented learning is the starting point. However, contrary to earlier approaches, where the provision or supply and use of high-quality information will automatically lead to learning and better performance, the focus is on acknowledging complexity, the need for interaction, and persuasion. Only in this way can evaluation help to create an environment that will foster the right learning processes. Evaluators should aim for maximal quality of delivery and interaction among stakeholders.

We will first describe the central aspects of the book: success and effective demand.

Success: How to Perceive This?

At first sight the concept of success appears to be straightforward. It implies that someone has succeeded in something. Indeed, various dictionaries define success through the achievement of something planned, desired, or attempted, or the attainment of something valuable such as wealth, favor, or eminence, and finally, that a social actor has attained more objects (such as money or fame) relative to another social actor. Yet from a sociological point of view, the underpinnings of the concepts are somewhat more elusive. Success for whom and defined by whom has distinct relations to social order, power, and even institutional arrangements within society. Therefore, one may infer that success is never innocent. Success is contextual insofar as what is deemed valuable may differ from one social context to another. It is also relational insofar as it implies that someone is more successful than someone else. Finally, success is situational insofar as it is negotiated in a social realm among social actors.

Further, one can discern at least three dimensions of success: perceived, ...