- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Civil Engineering of Canals and Railways before 1850

About this book

Between 1750 and 1850 the British landscape was transformed by a transport revolution which involved engineering works on a scale not seen in Europe since Roman times. While the economic background of the canal and railway ages are relatively well known and many histories have been written about the locomotives which ran on the railways, relatively little has been published on how the engineering works themselves were made possible. This book brings together a series of papers which seek to answer the questions of how canals and railways were built, how the engineers responsible organised the works, how they were designed and what the role of the contractors was in the process.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Civil Engineering of Canals and Railways before 1850 by Michael M. Chrimes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Canals and river navigations before 1750

A.W. Skempton

I. Introduction

IT is well known that the English canals of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries served as the arteries of the industrial revolution, but even in pre-industrial times the rivers and canals of Europe and Asia played a significant part in trade and commerce. One reason for this is that rivers (and canals are but extensions of river-systems) form the most natural inland routes to and from sea-ports. Moreover, so long as men and horses provided the only practical source of motive power for inland transport, heavy and bulky goods could be carried more economically and efficiently on water-ways than by any other means.

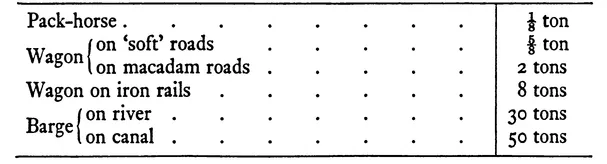

To illustrate this point quantitatively, the loads that can be carried or drawn by a single horse are set out in the table below. The gain in mechanical efficiency was partially offset by the greater capital expenditure required for the engineering works of the canal and river navigations; nevertheless the average cost of carriage by water In eighteenth-century England, for example, was rarely more than half and often only a quarter of the cost by road [1]. And the roads were frequently impassable for commercial traffic in winter.

Typical loads carried or drawn by a single horse

II. Transport Canals in China

The earliest major civilizations were in the valleys of the Euphrates, Nile, Indus, and Huang-Ho, and these great rivers provided a ready means of transport in addition to their life-giving supply of water for irrigation. The Phoenicians and the Greeks were maritime peoples, while the Romans chiefly made use of the many naturally navigable rivers in their empire. Apart from a few notable canals such as that from the Nile to the Red Sea, cut by order of Darius c 510 B.C., and several in France, Lombardy, and the Netherlands made during Roman times, the first sustained effort in canal-construction was made by the Chinese [2]. Among the more important of their works are the Ling Ch'u canal in Kuangsi (215 B.C.), the 90-mile-long canal from the Han capital Ch'ang-an to the Yellow River (133 B.C.), the Pien canal in Honan (A.D, 70), the Shanyang canal in Chiangsu (A.D. 350), and the first sections of the Grand Canal completed in 610. This had a total length of 600 miles, and along its banks ran an Imperial road planted with elms and willows. It served to transport grain from the lower Yangtze and the Huai to Kaifeng and Loyang. Under the T'ang dynasty in the eighth century the traffic on the canal was known to exceed 2 million tons annually.

In most cases the land traversed by these canals had a small gradient, and water-levels could readily be controlled by single gates separated from each other by considerable distances. For instance, on the Pien canal in A.D. 70 the engineer Wang Ching built the gates typically some 3 miles apart. They consisted of stone or timber abutments, each with a vertical groove into which squared logs of timber could be lowered or raised by ropes attached to their ends (plate 18). These simple stop-log gates evidently derived from the sluices used on irrigation canals. On the smaller transport canals, and especially in places where an appreciable difference in land-level had to be overcome, a double slipway was usually built, over which the barges were hauled. References to this device occur in Chinese literature at least as early as A.D. 348.

Occasionally a more elaborate gate was adopted, in which a solid door could be raised or lowered by a windlass. Two of these were built by Ch'iao Wei-Yo in 984 to replace a double slipway, during the remodelling of a section of the Grand Canal, and by placing the gates only 250 ft apart he created the first known example of the canal-lock: a device of fundamental technological importance. With single gates widely spaced along a canal or river considerable delays and great losses of water are involved in waiting for the levels to equalize after any particular gate has been opened, unless the difference in level is slight. With the lock, however, only the comparatively small volume within the lock-basin has to be filled or emptied, and the water-level in the long reaches or pounds between two locks is never altered.

It is rather curious, therefore, to find that little use was made of the lock in China. Its later development was entirely due to western engineers. Yet, if the Chinese remained content, in general, with their stop-log gates and slipways, they nevertheless achieved canal-works on a most impressive scale. Outstanding among these was the construction, between the years 1280 and 1293, of the northern branch of the Grand Canal from Huaian to Peking, having a length of 700 miles. Parts of this utilized existing rivers, and other sections were 'lateral' canals; but the section crossing the Shantung foothills, completed in 1283, was the earliest example of a 'summit-level' canal. A lateral canal has a continuous fall in one direction and, with intakes from the river alongside which it runs, there are few problems in water-supply. The conception of a lateral canal is relatively simple, since it is essentially an improvement of an existing river. In contrast, the idea of taking a canal over the summit of a watershed dividing two rivers requires bold imagination and considerable technical skill in providing an adequate water-supply at the summit. The Shantung section of the Grand Canal linked the Yellow River with a group of lakes, situated some 100 miles to the south at approximately the same elevation as the river. But over a short length the intervening land rose to a height of about 50 ft above the river and the lakes. The upper part of the canal was taken in a cutting with a maximum depth of 30 ft, yet this still left a fall of 20 ft to the north and south. To provide for the inevitable losses of water occasioned by operating the gates, two small rivers situated to the east, higher up the foothills, were partially diverted to flow into the summit-level. The engineers of this notable undertaking were Li Yueh and Lu Ch'ih.

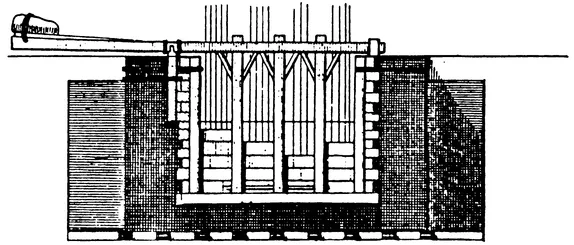

FIGURE 277—Section of a typical stanch or flash-lock. From Belidor, 1753.

III. Medieval Canals and River Works

At the time when the Grand Canal of China was completed, water-transport in Europe was still in a primitive state. Few canals had been constructed, and rivers were chiefly used as a source of power for water-mills. On many rivers each mill had its weir, to provide an adequate head of water for the mill-wheel, and these weirs were a serious obstacle to navigation. In the later Middle Ages, however, important developments took place in the Netherlands, as we shall see, while throughout the more commercially active countries of Europe improvements were made in the rivers by building stanches in the weirs and also at intervals along the river, between the mills, to reduce the gradient and increase the depth of water in the shallow places [3].

A typical stanch (also called a flash-lock or navigation-weir) is shown in figure 277. When a boat wished to pass, the wooden boards or 'paddles', with their long handles, were lifted out, and after the rush of water had somewhat abated the balance-beam, with the vertical posts which had supported the paddles, could be turned aside to leave a clear opening. Often the boats had to be hauled through against the flow, by a winch placed on the bank upstream of the stanch; in travelling downstream boats would find the 'flash' of water released by opening the stanch a help in crossing any shoals below it.

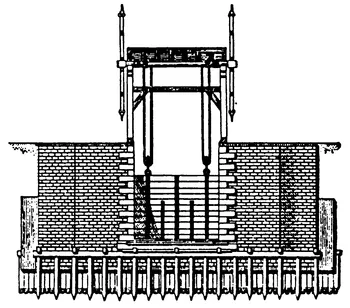

FIGURE 278—Section of a typical 'portcullis' sluice. From Belidor, 1750.

The early history of stanches is obscure, but it is practically certain that they were in existence on a number of rivers in Flanders,1 Germany, England, France, and Italy before the end of the thirteenth century. A reference to the winch for a stanch on the Thames at Marlow occurs in 1306. The oldest complete account of the Thames navigation between Oxford and Maidenhead, in 1585, shows twenty-three stanches; all but four were situated in the weirs of the mills on this 62-mile stretch of river [4]. Many of these stanches were still in place in the mid-eighteenth century, while as recently as the early nineteenth century twenty-two stanches were to be seen on the Marne between Châlons and Paris.

The very existence of Holland depends upon the dikes and drainage canals, and it is not surprising that some of the canals were enlarged and suitably equipped for transport at an early date. Originally the drainage canals had outlets through the dikes controlled by sluices. In some cases goods had to be transhipped over the dike, and in other places boats were hauled over a double slipway similar to those in China.2 Perhaps the first examples were at Het Gein and Otterspoor, built in 1148 on the Nieuwe Rijn canal near Utrecht. Where hydraulic conditions permitted, an obvious improvement was to make the sluice-gate large enough for the passage of boats. These navigation sluices in Holland were of the lifting-gate or portcullis type shown in figure 278, When the tide in the estuary or river was at the same level as the water in the canal, the gate was raised by a windlass and boats could pass through. At other states of the tide a difference in water-level existed across the gate. To safeguard the sluice from under-seepage the foundations and abutment-walls were extended, typically 20 or 30 ft beyond the gate and also well into the body of the dike. Figure 278 represents a sluice built in 1708; it will be seen that the danger of under-seepage is further prevented by sheet-piling. This was a characteristic feature of construction in the sixteenth century and later, but seems to have been unknown to medieval engineers. A magna slusa at Nieuport, mentioned in 1184, may have been of the portcullis type, as also the sluice at Governolo on the river Mincio, built in 1188-98 by Alberto Pitentino, and that at Gouda of c 1210,

The next step was of vital importance. It in...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- General Editor's Preface

- Introduction

- PART ONE: CANALS

- PART TWO: RAILWAYS

- Index