![]()

1

The social and behavioural aspects of climate change

Linking vulnerability, adaptation and mitigation

Chiung Ting Chang and Pim Martens

ICIS, Maastricht University, The Netherlands

Bas Amelung

Amelung Advies, The Netherlands

The VAM programme targets four main themes: vulnerability, adaptation, mitigation, and adaptation-plus-mitigation. In the brochure that accompanied the call in 2004, the programme committee hinted at the political connections between these themes: ‘Until recently, social scientific climate research was dominated by the strategy of mitigation, in the wide sense, and in particular the analysis of reduction measures. Yet at COP8—the eighth session of the “Conference of the Parties” in the “United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change” (UNFCCC) [in 2002]—the developing countries were strongly in favour of adaptation. The two subjects are most likely to be pitted against each other in future negotiations.’ This was indeed the case at the following COP sessions, including the one in Copenhagen in December 2009. The emphasis of the developing countries on adaptation is likely to be related to their perceived vulnerability: the extent to which health, economy, and nature and biodiversity will be affected as a result of a certain climatic change. The developing countries are generally considered to be more vulnerable than the industrialised nations.

This chapter’s objective is to move beyond an intuitive and political understanding of how the VAM themes are connected. It aims to provide a conceptual framework of the VAM themes and their linkages. Such a framework brings the underlying connections between the (perhaps seemingly disparate) VAM projects to the fore. The chapter also touches on some of the latest trends in climate research in the social sciences, so that the individual projects can also be positioned against that background.

1.1 Vulnerability, adaptation and mitigation: the climate change agenda

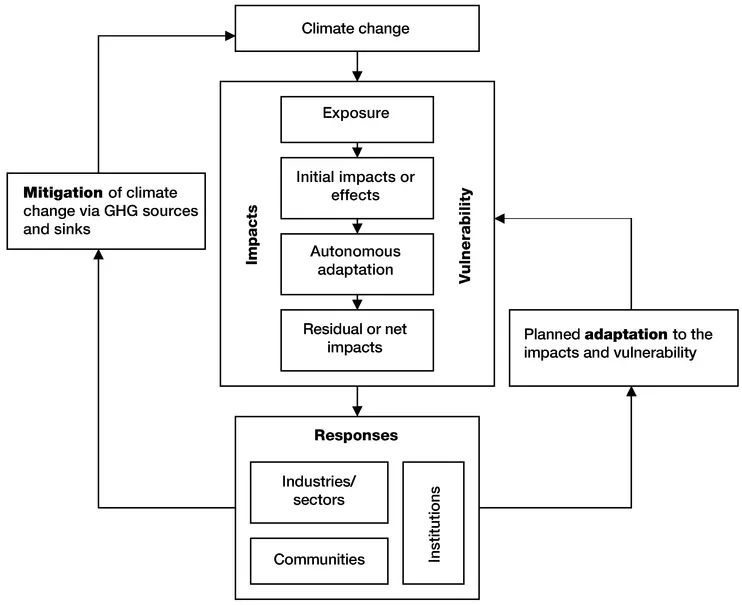

Smit et al. (1999) propose a schematic representation of the links between vulnerability, adaptation and mitigation. The scheme was later adapted by Martens et al. (2009), and further revised here (see Fig. 1.1). The scheme can be read as follows. Human interference with the global carbon cycle and other natural processes leads to changes in the climate system. These changes can manifest themselves in many different ways, such as temperature increases, sea level rise, reduced precipitation, and more intense rainfall. Such manifestations vary widely in both space and time, and their relevance differs strongly between economic sectors and regions. Exposure to climate change therefore not only depends on the physical realities of climate change, but also on the characteristics of the system (e.g. region, country, company or economic sector) exposed. How exposure translates into initial impacts depends on the sensitivity of the system: for example, a slight change in precipitation patterns may be sufficient to make the cultivation of a certain crop unprofitable, whereas large increases in summer temperatures may hardly affect the popularity of certain beach resorts.

Typically, systems resist change; they respond to the initial impacts of climate change by means of ‘autonomous adaptation’. For example, a farmer may decide to replace a crop that cannot cope with the changes in climate conditions by a crop thriving on these same changes. It is a matter of dispute what exactly differentiates ‘autonomous adaptation’ from ‘planned adaptation’, which also features in the scheme. According to Smit and Pilifosova (2001), ‘planned adaptation’ involves some form of public coordination through government intervention, whereas ‘autonomous adaptation’ occurs through private actors. Another key distinction is that autonomous adaptation is always reactive, whereas planned adaptation may be proactive as well. The residual or net impacts that result after autonomous adaptation are usually smaller than the initial impacts. In some cases, however, positive feedback effects may be at work that reinforce rather than dampen the initial effects.

Governments and other actors can respond to (projected) impacts by taking policy measures. One type of response is to mitigate, i.e. to reduce greenhouse gas emissions or to capture and store emissions. The other type of response is to adapt to the (projected) impacts in order to reduce any negative effects and foster any positive effects, or to reduce vulnerabilities. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2001) defines vulnerability as ‘the degree to which a system is susceptible to, or unable to cope with, adverse effects of climate change, including climate variability and extremes’. The IPCC conceptualises vulnerability as being composed of three elements: exposure, sensitivity and adaptive capacity. Policy responses aimed at reducing vulnerability can operate on any of these three components. Exposure can be reduced (e.g. by changing the sectoral composition of the economy), sensitivity can be reduced (e.g. by making operational adjustments), and the adaptive capacity can be increased (e.g. by making contingency plans).

Figure 1.1 The analytical framework for vulnerability–adaptation–mitigation research in the context of climate change

Source: adapted from Martens et al. 2009

Since 1999, when Figure 1.1 was devised, climate change research has changed. Martens et al. (2009) summarise four key developments. The first is an increase in scientific consensus concerning climate change. Through the IPCC, the collaborative efforts of scientists have concluded that climate change is happening and, importantly, that human activity is making a discernible contribution to this change. The second development is a shift of focus from impacts to risk management. This means going beyond mere consideration of climate-related hazards, to more explicit considerations of issues surrounding the vulnerability and exposure of different elements at risk, as well as addressing conditions of uncertainty. The third development is the consideration of non-climate stressors, acknowledging that the climate is not the only driver of change in our societies. Finally, policy and research agendas have become less dominated by mitigation. There is an increasing awareness that actors also need to be preparing for changes that are unavoidable. This has resulted in a greater consideration of vulnerability and adaptation, and recognition of the need for better interdisciplinary cooperation. Improved linkages between natural and social scientists will be crucial in order to effectively address the complexities of climate change.

Klein et al. (2007) deduced four possible connections between mitigation and adaptation: adaptation actions that have consequences for mitigation; mitigation actions that have consequences for adaptation; decisions that include trade-offs or synergies between adaptation and mitigation; and processes that have consequences for both adaptation and mitigation. Obvious as this list may look, connecting the policy and research efforts regarding mitigation and vulnerability/adaptation is a formidable challenge. Martens et al. (2009) explored the potential and pitfalls, which are introduced below. Before doing so, however, it is perhaps good to note that few, if any, of these challenges are restricted to the endeavour of connecting the domains of mitigation and adaptation. Perhaps they reach their maximum acuteness in connecting these domains, but for the most part the challenges are common features of climate research at large.

First, a common link between mitigation and adaptation is the capacity of a system to respond. For example, adaptive capacity can be simply defined as the ability of a system to adjust to climate change; this is thought to be determined by a range of factors including technological options, economic resources, human and social capital, and governance. Mitigation has similar determinants—in particular, the availability and penetration of new technology. Although technological solutions have a role to play in both mitigation and adaptation, it should be recognised that ‘soft engineering’ has a particularly important role in adapting to climate change. The willingness and capacity of society to change is also critical. Information and awareness-raising can be useful tools to stimulate individual and collective climate action (McEvoy et al. 2006).

Second, an integrated response is challenging as there is a mismatch between mitigation and adaptation in terms of scale, both spatially and temporally. Mitigation efforts are typically driven by national initiatives operating within the context of international obligations, whereas adaptation to climate change and variability tends to be much more local in nature, often in the realm of regional economies, communities, land managers and individuals. Besides the spatial element, there are also differences in the timing of effects. As greenhouse gases have long residence times in the atmosphere, the results of mitigation action will be seen only in the long term. Adaptation, on the other hand, has a stronger element of immediacy. Regional differences and the dynamic features of vulnerability and averting behaviour should therefore be taken into account in both theoretical and practical analyses.

Third, disconnection in space and time can make it difficult for people to link the consequences of their activity with long-term environmental consequences. It also raises the question of environmental equity: that is, who are the likely beneficiaries of the different types of response? Mitigation, being an action targeting the long term, means attaching value to the interests of future generations and to some extent can be considered an altruistic response by society. Conversely, the impacts of climate change are felt more immediately by individuals in society and adaptation is typically viewed as obeying the everyday ‘self-interests’ of individuals. As such, studies on risk perception by individuals, industries and organisations will be critical to understand its influence on the acceptability and ultimate effectiveness of different responses.

Fourth, mitigation and adaptation have different distributional effects: in particular, who pays and who gains, and whether there is a willingness to invest if the benefits of adaptation are perceived to be private. It is also important to note discrepancies in that those responsible for the majority of emissions (i.e. developed countries) also have the highest adaptive capacity, while the poorest countries, producing the lowest emissions, are most vulnerable to the impacts of a changing climate. Consequently, the urgency that different countries attach to any mitigation response varies widely. The same phenomenon holds true within national territories where uninsured, unaware and relatively immobile populations living in poorer-quality accommodation are often the hardest hit. This means that, in reality, those most vulnerable to climate change are often those already socioeconomically disadvantaged in society. Thus, not merely geo-physical vulnerability but also socioeconomic vulnerability should be taken into account. Studies on distributional effects and cost–benefit analysis of mitigation, adaptation and mitigation-plus-adaptation measures will contribute to the analyses of trade-offs and avoidance of unwanted side effects,

Finally, another important difference between mitigation and adaptation relates to those who are directly involved. Mitigation policy is primarily focused on decarbonisation and involves interaction among the large emitting sectors such as energy and transport, or else targets efficiency improvements according to specific end-users—commercial and residential. The limited number of key personnel, and their experience in dealing with long-term investment decisions, means that the mitigation agenda can be considered more sharply defined. In contrast, the many actors involved in the adaptation agenda, in contrast to mitigation policy, come from a wide variety of sectors that are sensitive to the impacts of climate change and operate across a wide range of spatial scales. As a result, the implementation of adaptation measures is likely to encounter greater institutional complexity than the implementation of mitigation policies. A relevant research question is therefore how formal and informal institutional conditions affect socioeconomic vulnerability, adaptive capacity and mitigation choices.

1.2 Outline of the book

The above-mentioned developments and challenges underscore the relevance and timeliness of the VAM programme. Below is an outline of the structure of the book and a brief introduction to the various chapters. The diversity of projects made it difficult to cluster the projects around a small number of themes, although one option available to us was to organise the book according to the four VAM themes. The portfolio of VAM projects is reasonably balanced in terms of representation of these themes. Vulnerability and adaptation (which are often highly interlinked within projects) are the focus of six out of 12 projects, as well as the collection of essays. Four chapters have an emphasis on mitigation, while the two remaining chapters address the interaction between adaptation and mitigation. While consistent with the VAM scheme, a structure based on the main themes provided little coherence within the resulting sections.

Other dimensions for classification included geographical scale, temporal scale, and scientific discipline, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. A workable structure for the book resulted from a hybrid framework for classification, made up of three sections: industry/sector, community, and institution. This classification has an element of ‘nesting’: an industry may be part of a community, and a community in its turn belongs to a society with institutions. It also contains an element of increasing institutional complexity, with trade-offs being clearer or more easy to resolve for industries than for communities, and the level of society being even more complex. These ideas were used only as ordering principles; it is fully acknowledged that they do not always do justice to the levels of complexity found in sectors and communities.

Chapters on inland navigation, tourism, partnerships, and energy conservation in housing make up the section on industries. The communities section contains chapters on the impact of Hurricane Mitch on Nicaragua, local adaptation in Mozambique and the Netherlands, and 3D simulation of flood events. Finally, the section on institutions is made up of chapters on white certificates, EU climate change law, the legal challenges of applying the precautionary principle, and the explicit incorporation of adaptation into Integrated Assessment models. Each of the chapters is introduced in somewhat more detail below.

1.3 Industries

Industries contribute substantially to the emission of CO2 and other greenhouse gases. At the same time, they face significant economic losses as a result of climate change. Some industries are particularly vulnerable to climatic changes. Inland navigation for instance, discussed in Chapter 2 (‘Climate change and inland navigation between the Netherlands and Germany: an economic analysis’), is subject to changing water levels and is susceptible to hydrological extremes. The sector is expected to suffer both in winter and in summer. In winter, more navigation delays on the River Rhine are likely to occur due to higher water levels, whereas in summer transport capacity will be reduced owing to lower water levels. Both transport volumes and speed are negatively affected. Chapter 2 estimates economic losses and analyses how these are distributed between the upstream and downstream countries of Germany and the Netherlands. In addition, the chapter explores the possible adaptive measures by examining the relationships between transport carriers and their clients.

Tourism is another industry in Europe that is particularly vulnerable to changing climatic conditions, as well as climate policy. Many tourism activities require favourable conditions for their success, and tourism is increasingly reliant on energy-intensive forms of transport that are likely to be affected by mitigation measures. The economic stakes are high. In 2008, Europe earned US$435 billion from international tourism alone (UN World Tourism Organization 2009), a significant share of which is climate-driven. Chapter 3 (‘Climate change impacts: the vulnerability of tourism in coastal Europe’) adds to the scarcely available knowledge on the climate preferences of tourists. Furthermore, it analyses the likely consequences of climate change for the spatial and tempor...