eBook - ePub

Sustainable Resource Management

Global Trends, Visions and Policies

- 338 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Sustainable Resource Management

Global Trends, Visions and Policies

About this book

Looking at material flows, industrial and societal metabolism and their implications for the economy, this book provides radical perspectives on how the global economy should use natural resources in intelligent ways that maximise well-being without destroying life-supporting ecosystems.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sustainable Resource Management by Stefan Bringezu, Raimund Bleischwitz, Stefan Bringezu,Raimund Bleischwitz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Stefan Bringezu and Raimund Bleischwitz

The best resource is the one we don’t need.

In late 2008 and early 2009 an economic crisis surfaced. Many people have focused on the financial crisis and its implications for industries and economies worldwide. Others refer to the ongoing environmental crisis, most notably to climate change. This book spreads a simple message: the bailout of the economic and environmental crisis requires the build-up of sustainable capital.

Understanding the multifaceted roots of the current crisis is a key to turning it into opportunities. This book is about sustainable resource management. We argue that all economies depend on using natural resources in intelligent ways that maximise well-being without hampering the capacities of life-supporting ecosystems.

Europe’s economy is based on global resource use. Material commodities are sourced from various regions in the world. At the same time, European resources—raw materials and know-how—are used to supply other countries with products and services. In a globalising world, process chains from resource extraction and refining to manufacturing, use, recycling and final disposal are becoming increasingly complex. At the same time, all these material flows constitute the physical basis of our societies—called the ‘socio-industrial metabolism’. A main premise of this book is to explain its characteristics and dynamics in order to reveal robust findings about basic constraints, as well as key options, for future development.

The impacts of ever-increasing global resource use are becoming more and more obvious. An increasing number of local and regional conflicts have arisen from the competition over natural resources and the limitations following their use. The opening of new mines, which require more and more land due to declining ore grades, often causes conflict with agriculture over water issues. Urban sprawl covers the most fertile soils and reduces production capacity for biomass. The expansion of agriculture for the production of non-food biomass, for instance for biofuels, transforms natural forests and savannahs into cropland with various impacts on biodiversity and the quality and function of the living environment. The energetic use of fossil resources is only part of the problem because the dominant share of material flows are induced for non-energetic purposes: it is the demand for semi-manufactures in industry and final products and services in private households that drives the turnover of the socio-industrial metabolism and the resulting magnitude of environmental impacts.

Yet unknown interconnections on a worldwide level lead to a number of issues. With growing distances between the origins of resource extraction and final consumers it becomes increasingly difficult to determine accountability and search for effective ways of improving the management of natural resources. Financing is but another example: is it pure speculation to believe that real estate markets did not properly take into account the necessary balance between new dwellings, refurbishing of existing buildings, deconstruction and physical infrastructures? Furthermore, with prices for natural resources starting to surge in the year 2000, did the financial markets overlook the implications for demand and abilities to repay interest rates?

Better knowledge about the long-term dynamics and basic conditions of our material basis may enable decision-makers to adjust economic activities in a timely manner, reduce the risk of sunk investments and spur technological and institutional development with a higher chance for returns. Strategic planning would benefit from such know-how, which might also stimulate discovery of new and promising business fields.

Any crisis also provides opportunities. Analysis of natural ecosystems has shown that phases of climax are often superseded by a phase of reorientation and restructuring. History also reveals many lessons on relaunching development—the setting up of the European Union after the Second World War being perhaps the most prominent example. There is no reason to believe that the end of history, as Francis Fukuyama once coined it, is near. Under

Key message 1 Not only do the dynamics of the volume and structure of the socio-industrial metabolism and its spatial rooting and land-use pattern determine the quality of the environment. The socio-industrial metabolism’s growth and composition also determine the quantitative and qualitative relationship between natural and human systems.

standing long-term change in both dimensions—the physical and the socio-economic—provides us with key ingredients on critical dynamics and basic options for diversion that aid the search for future pathways.

In general, the long-term development of ecosystems and its components— and probably also the biogeosphere–human system—follows an adaptive cycle (see Box 1.1). The analogy to the human system seems straightforward, insofar as effective institutions would be needed to adjust production and consumption processes towards a pathway in which environmental impacts (e.g. through climate change and unsustainable resource use) are mitigated and adaptation capacity to changing conditions is increased. Research findings by, for example, Douglass C. North (1994) exactly point in that direction. In addition, the concept of evolutionary competition as developed by Wolfgang Kerber (Kerber and Saam 2001) underlines the openness of change and the permanent striving for new knowledge to solve problems.

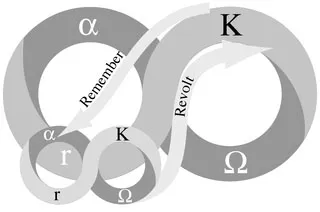

Box 1.1 The adaptive cycle of systems change1

In an early phase of system development, species with high growth rates (r-phase of exploitation)2 are pioneering the landscape. They compete in a scramble competition (the first to get the prize wins) to exploit the available resources such as nutrients, light and space. In the subsequent K-phase of conservation, species with low growth rates, which use resources more efficiently, are competing in a contest competition (through specialisation and the build-up of different material cycles). As a result the production and consumption (as well as the accumulated material stock) of the ecosystem gradually reaches its maximum capacity (K). Shock events such as forest fires, floods, droughts, insect pests or intense pulses of grazing, may then induce ecosystems to break apart in an omega (Ω) phase and release their accumulated nutrients in a kind of a ‘creative destruction’ (a term popularised by J. Schumpeter). This may give rise to the alpha (α) phase where a ‘reorganisation occurs’; nutrients are converted by soils into compounds which can again be used by pioneer plants and thus form the basis for the next cycle.

FIGURE 1.1 Scheme of the adaptive cycle of (eco)systems Source: www.resalliance.org/593.php, accessed 25 May 2009; adapted by P. Bunnell from Panarchy by L.H. Gunderson & C.S Holling. Copyright © 2002 Island Press. Reproduced by permission of Island Press, Washington, D.C.

The development from r to K phases is characterised by increasing capacities for innovation and change, similar to the growth of knowledge in developing and advanced countries. And it is usually coupled with better institutions, that is, the ‘strength of internal connections that mediate and regulate the influences between inside processes and the outside world—essentially the degree of internal control that a system can exert against external variability’ (Holling and Gunderson 2002: 50). Development at different scales is also interconnected. For instance, a ‘revolt’ occurs when fast, small events overwhelm large, slow ones (e.g. a small fire in a forest spreads or a disruptive technology is deployed); and a ‘remember’ effect occurs when the potential accumulated at larger, slow levels influences reorganisation (e.g. after a forest fire processes at a larger level slow the loss of nutrients or stabilising institutions resist fast changes).

Nowadays, human societies seem to perform at different stages within such a cycle. Developing countries and in particular emerging economies, which are going to build up their infrastructures and after a time-lag experience enormous growth rates in production and consumption, seem to pursue the r-strategy—with the notable exception of ‘failing states’ that are loaded with historic constraints and are stuck between the omega and alpha part of the cycle. Richer societies, where economic growth rates have been slowing down, are more advanced with regard to the K-strategy—competition works towards product specialisation and higher resource efficiency. Nevertheless, within each country structural change takes place. Old industries may face an omega situation, like the breakdown of outdated facilities in Eastern Europe after the fall of the Iron Curtain, and find ways to reorganise in a modernised way. One may also note that this model does not necessarily imply progress, but also entails elements of downswing and destruction. In addition, the ability to absorb shocks and to overcome persistent failures is a key factor of long-term performance.

With regard to ‘development as freedom’—as Amartya Sen (1999) puts it—it is important to stress the seemingly unlimited ability of humans to create new opportunities, be it as adaptation to new circumstances, novelty or new technological devices or as a new means to organise collective action. Process-oriented innovation now leads to huge savings for material purchasing costs and contributes to the decoupling of resource use and economic growth. The ensuing resource efficiency, however, is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it allows provision of the same function with less material, energy, water and land. On the other hand, it allows the production and consumption of much more of those functions at a cheaper price. As a consequence, many efficiency improvements of the past have led to increased levels of production, and at least partially compensating resource savings. This so-called ‘rebound effect’ remains a challenge for the future and makes it necessary to account not only for enhanced ‘efficiency’ in a technological sense at the micro level of companies, but also for increased ‘productivity’ with regard to the overall performance of countries, economies and societies. In addition, it will be necessary to monitor the absolute amount of resource use and the specific environmental impacts thereof. The latter is inherently a public responsibility.

Today, the interconnectedness between countries and regions is growing, and the perception of mutual interdependence should serve as motivation for collective action. Self-interest of leading actors, new forms of strategic behaviour and unilateralism will certainly also be pursued. Nevertheless, there are strong incentives to foster models of cooperation, which in the long run may turn to symbiosis of complementary systems. Industrial systems have often been analysed to evolve into local and regional networks that optimise cascading use of material and energy flows (‘industrial symbiosis’). This research formed a nucleus for the wider field of ‘industrial ecology’ with analyses of all components of the economy and their relations with the environment from a systems perspective, often focusing on the options of increased recycling and the minimisation of pollution and waste (Ayres and Ayres 2002; Lifset and Graedel 2002), but also considering business and development opportunities (Erkman and Ramaswamy 2003), and a broader sustainability context (Ehrenfeld 2007).

Models of a recycling economy have been established and are going to be enlarged at the national, European and international level. For instance, China is actively promoting the notion of a circular economy (Yuan et al. 2008). Those new systems will perform better on a cooperative basis. Parallel to that, international organisations and treaties (e.g. the international Convention on Biological Diversity) will be essential to provide shelter for life-supporting ecosystems and other collective goods.

Key message 2 Restricting the use of natural resources to a sustainable level can be shaped into an opportunity if tools inherent to human beings are activated: the development of visions and institutions to govern change.

This book presents a vision that the current dynamics of physical expansion of the world economy is a rather early stage of development, which will be superseded by a phase of metabolic maturity where material flows will—to a much higher degree than today—be managed as internal recycling flows. Inherently, there will be vivid activities of physical growth and decline in various places in the world, which altogether would be in equilibrium. Like an adult organism that stops growing physically but (at least it is hoped) continues to grow mentally, future societies would not only increase their stock of knowledge and social capital, but also utilise it to use less natural resources. Stable stocks of buildings and infrastructures would not hinder further growth of monetary flows, especially as material efficiency, knowledge and social capital would continue to increase.

In the not too distant future, we envision a process whereby interregional and international cooperation manages to limit and reduce the absolute amount of resource extraction for internationally traded commodities and the extent of intensive land use according to world regions’ ecosystem capacities. Such a global governance system will be supported through resource management schemes and production and consumption policies, which allow regions to pursue their development pathways without depriving others, and future generations, of being able to meet their demands.

Consequently, the prevailing phenomenon of problem shifting plays a central role in this book. We can demonstrate in both conceptual and empirical terms that material and energy efficiency of the European economy—as in other economies—is increasing. At the same time, resources are imported to a growing extent from other regions, with an over-proportional growth of so-called ‘hidden’ flows: that is, resource extraction that burdens the environment but does not enter the traded product. In other words, Europe currently cleans up its environment—and related reporting—at the expense of others.

Problem shifting not only occurs between regions, but also between different environmental pressures. This book gives evidence as to how platinum group metals (PGMs) in car catalysts reduce air pollution on a large scale within Europe while their production causes significant pollution and mining waste at certain locations outside Europe. We also analyse the trade-off between the use of biofuels for greenhouse gas mitigation and the expansion of cropland at the expense of natural ecosystems. Box 1.2 contains seven principles of sustainable resource management that summarise our point of view.

In order to detect phenomena such as problem shifting, it is of paramount importance to apply a comprehensive systems perspective when analysing the socio-industrial metabolism. To understand these dynamics, we will analyse the driving factors behind resource use and explore the options to reduce resource consumption and enhance resource productivity, with the positive side-effects already mentioned.

Chapter 2 provides an overview of the methodological tools that allow analysis of the physical basis of our economies, from the product and firm level to sectors and whole countries, considering the flow of substances and bulk materials and the life-cycle-wide impacts on the environment. A set of economy-wide indicators is described that reflects the volume, structure and physical growth of the socio-industrial metabolism, resource productivity and the share of domestic and foreign resource use. Special attention is drawn to the interlinkage of material flows and land use. Accounting for the

Box 1.2 Seven principles of sustainable resource management

- Secure adequate supply and efficient use of materials, energy and land resources as a reliable biophysical basis for creation of wealth and well-being in societies and for future generations

- Maintain life-supporting functions and services of ecosystems

- Provide for the basic institutions of societies and their co-existence with nature

- Minimise risks for security and economic turmoil due to dependence on resources

- Contribute to a globally fair distribution of resource use and an adequate burden sharing

- Minimise problem shifting between environmental media, types of resources, economic sectors, regions and generations

- Drive resource ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Analysing global resource use of national and regional economies across various levels

- 3 Europe's resource use: basic trends, global and sectoral patterns, environmental and socioeconomic impacts

- 4 Visions of a sustainable resource use

- 5 Outline of a resource policy and its economic dimension

- References

- Acronyms and abbreviations

- About the contributors

- Index