![]()

1

The Changing Environment of Banks*

Marcel Jeucken

Rabobank, Netherlands

Jan Jaap Bouma

Erasmus University, Netherlands

Sustainable companies will need to consider their long-term strategies more seriously in business decisions. In fact, the very existence of many companies will depend either on the continued availability of certain natural resources or their ability to adapt and reinvent themselves.

So how is the banking sector responding to the new challenges that sustainability presents? Basically, it has responded far more slowly than other sectors. Bankers generally consider themselves to be in a relatively environmentally friendly industry (in terms of emissions and pollution). However, given their potential exposure to risk, they have been surprisingly slow to examine the environmental performance of their clients. A stated reason for this is still that such an examination would ‘require interference’ with a client’s activities. Empirical research from 1990 concluded that (European) banks were not interested in their own environmental situation nor that of their clients (Tomorrow 1993).

This situation is now changing. There is growing awareness in the financial sector that environment brings risks (such as a customer’s soil degradation) and opportunities (such as environmental investment funds). On the risk side, there has been an enormous raising of concern in the United States since the late 1980s. Banks could, under CERCLA,1 be held directly responsible for the environmental pollution of clients and obliged to pay remediation costs. Some banks even went bankrupt under this scheme. Due to these developments, American banks became the first to consider their environmental policies, particularly with regard to credit risks. European banks were not exposed to these liabilities and only began to develop policies toward environmental issues during the mid-1990s. The focus here was less on risk assessment and more on the development of new products such as environmentally friendly investment funds.

Both risk and opportunity are now becoming established elements in banking policies towards the environment. Empirical research on the environmental activities of banks by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) in 1995 stated that 80% of the respondents made some kind of assessment of environmental risks (UNEP 1995). An investigation from 1997 concluded that many banks have set up environmental departments and are developing environmentally friendly products (Ganzi and Tanner 1997). In Asia, South America and Eastern Europe, change is also under way, mostly through the influence of environmental standards from multilateral development banks, such as the World Bank, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the Andean Development Corporation (ADC) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD).2 Strong evidence that sustainability has reached the mainstream financial community was provided by the launch of the ‘Dow Jones Sustainability Group Index’ in September 1999 (DJSGI 1999). For the first time, a mainstream global index is tracking the performance of the leading sustainability-driven companies worldwide.3

The role of banks in contributing toward sustainable development is potentially enormous, because of their intermediary role in an economy. It is exactly this intermediary role that has attracted the interest of governments and institutions such as the EU and UNEP in their environmental activities (UNEP 1997; European Commission DG XI 1998). Banks transform money in terms of duration, scale, spatial location and risk and have an important impact on the economic development of nations. This influence is of a quantitative, but also of a qualitative, nature, because banks can influence the pace and direction of economic growth.

At the Earth Summit in 1992, the ‘UNEP Financial Initiative on the Environment and Sustainable Development’ was established in order to initiate a constructive dialogue between UNEP and financial institutions. The financial sector incorporates a broad set of institutions, which includes commercial banks, investment banks, venture capitalists, asset managers, multilateral development banks and rating agencies. The mission statement of this initiative declares:

This initiative, which operates under the auspices of the United Nations Environment Programme, promotes the integration of environmental considerations into all aspects of the financial sectors’ operation and services. A secondary objective of the initiative is to foster private sector investment in environmentally sound technologies and services (UNEP 1999).

The initiative ultimately resulted in a statement by banks (the ‘UNEP Statement by Financial Institutions on the Environment and Sustainable Development’ in 1992) and by insurance companies (‘Insurance Industry Initiative for the Environment, in association with UNEP’ in 1995). At the beginning of November 1999, approximately 160 banks and approximately 85 insurance companies had signed the respective statements.

This chapter explores the role of banks in the progress toward sustainable development. First, we map out the role of banks in a macroeconomic system by looking at their products in general. We then analyse the environmental impacts of banking, before describing the driving forces on banks to take environmental action. In the subsequent section we present a typology of the actions that banks are taking. We then examine the role of governments in establishing a role for banks in achieving sustainable development, with particular regard to the experience of the Netherlands. Finally, we provide some conclusions about the current dynamic and likely changing role of banks in the future.

1.1 The role of banks

Banks have an important role in an economy: they are intermediaries between people with shortages and surpluses of capital. Their products include savings, lending, investment, mediation and advice, payments, guarantees, and ownership and trust of real estate. These core activities generate two principal sources of income: interest earnings and provision earnings. In the first case, a bank is working on its own behalf and risk; and in the second case on behalf of and at the risk of its clients. It is usual to distinguish between different banking departments such as investment banking, commercial banking, corporate banking, private banking, trade finance, electronic banking, securities, financing and loans, savings and so on. Some banks specialise in one or more of these areas. Universal banks usually cover all activities.

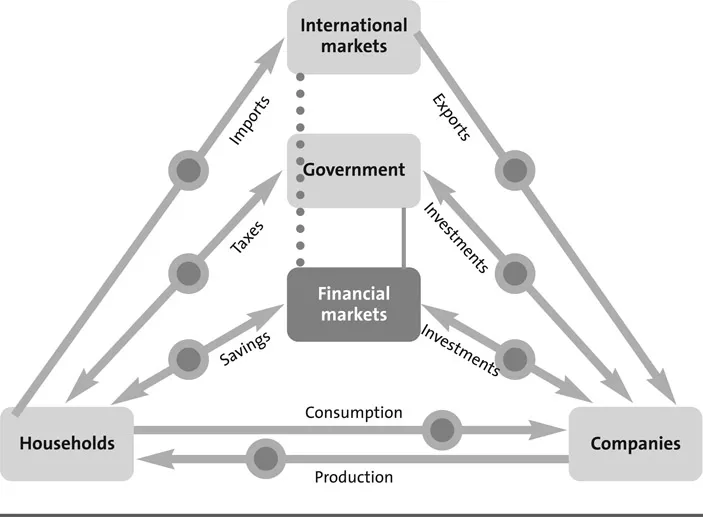

Figure 1.1 represents the typical cyclical process of a macroeconomic system. In this simplistic model one can clearly see at which points in an economy banks are present and have influence (represented by the shaded areas). The arrows represent money flows. Households pay taxes, consume and import goods and save money. Companies produce, invest and export goods and receive investments. Governments receive taxes, pay subsidies and invest. Through the international markets, goods (imports and exports) are traded. Surpluses and shortages of the government, the international markets, companies and households are dealt with by financial transactions through the financial markets. The importance of the financial markets is evident. In many countries, banks are the most important financial intermediaries in an economy.4 The traditional intermediary role has consisted mainly of bridging savings and investments. Today, it more usually consists of bringing together people with shortages and people with surpluses of capital. The traditional profits of banks have largely consisted of interest earnings. Today, and due to this shift, more than half the profits of banks are often generated through provision earnings. Securitisation and investment banking are important examples of this shift, which is of some importance with regard to sustainability because it involves the increasingly direct influence of clients on the investments that banks make.

Figure 1.1 The role of the financial markets in an economic system

As a financial intermediary between market players, a bank has four important functions:

- First, it transforms money by scale. The money surpluses of one person are mostly not the same as the shortages of another person.

- Second, banks transform money by duration. Creditors may have short-term surpluses of money, while debtors mostly have a long-term need for money.

- Third, banks transform money by spatial location (place). For example, a bank brings money from a creditor in New York to a debtor in London.

- Finally, banks act as assessors of risk. As a rule, banks are better equipped to value the risks of various investments than individual investors who have surpluses available. In addition, through their larger scale, banks are more able to spread the risks.

This last function in particular is of importance with regard to the achievement of a sustainable society. Banks have extensive and efficient credit assessment systems and because of this they have a comparative advantage in knowledge (regarding sector-specific information, legislation and market developments). Through this knowledge of environmental and financial risks, banks fulfil an important role in reducing the information asymmetry between market parties. A bank will attach a price to this reduction of uncertainty (through, for example, its interest rates). So tariff differentiation for sustainability can be justified from a risk standpoint: clients with high environmental risks will pay a higher interest rate. The possibilities for tariff differentiation will be even larger if banks can attract cheaper money—by paying less interest for their own funding because of the relatively high quality and lower risk of their credit portfolio. This tariff differentiation by banks will stimulate the internalisation of environmental costs in market prices. In this sense, banks are a natural partner of governments.

A sustainable bank may well go a qualitative step further and contribute to sustainability on ideological grounds as well as on risk assessment grounds. Through their intermediary role, banks may be able to support progress toward sustainability by society as a whole—for example, by adopting a ‘carrot-and-stick’ approach, where environmental front-runners will pay less interest than the market price for borrowing capital, while environmental laggards will pay a much higher interest rate. This may result, at least initially, in a loss of profitability, but certainly doesn’t require a loss of continuity.

The question is if, or to what degree, banks are willing to take such steps. Schmidheiny and Zorraquín’s book, Financing Change (1996), asks the fundamental question whether banks are a driving force or a hindering force for sustainability:

Do the financial markets encourage a short-termist, profits-only mentality that ignores much human and environmental reality? Or are they simply tools that reflect human concerns, and so will eventually reflect disquiet over poverty and the degradation of nature by rewarding companies that treat people and the environment in a responsible manner? (Schmidheiny and Zorraquín 1996: xxi).

Schmidheiny and Zorraquín conclude (based on interviews throughout the financial sector) that banks are not hindering the achievement of sustainability. We believe that this conclusion may be flawed. Intuitively, banks have a hindering role in the achievement of sustainable development. First, they prefer short-term payback periods, while many investments necessary for achieving sustainability must be long-term. Second, investments that take account of environmental side-effects usually have a lower rate of return, while financial markets usually look for investments with the highest rate of return. It is therefore the case that sustainable investments are unlikely to find sufficient funding within the current financial markets.

In an economic paradigm of profit and benefit maximisation, companies and households will not take account of the environmental side-effects of their economic decisions as long as the environment is not represented in the prices on which they base these decisions. There will always exist an alternative investment that will yield a higher profit or benefit than an investment that takes into account all environmental side-effects. For example, an investment in a factory that legally pollutes heavily (and passes the cost burden onto society at large) will—ceteris paribus—have a higher rate of return than a factory that has invested in expensive technologies to combat that pollution. Banks will often reward the first company with a lower cost of capital or request for collateral. In the long run, an investment in the second factory would have been a better investment for the bank (and society at large), but, by the time the first factory is confronted by tougher legislation, greatly increased costs and even threats to its licence to operate, the bank has made its profit and pulled its money out of the factory (ceteris paribus).

If Schmidheiny and Zorraquín are right after all, then the ‘highest return effect’, as outlined above, has to be overcome by far stricter environmental legislation and enforcement or dynamic environment-related market developments. An alternative reason for banks not to hinder progress toward sustainable development is stakeholder pressure—such as NGOs, shareholders and employees—to act ‘sustainably’ (see Section 1.3).

1.2 The environmental impacts of banking

To understand the environmental impacts of banks, one has to make a distinction between internal and external issues.5 Internal issues are related to the business processes within banks, while external issues are connected to the bank’s products.

1.2.1 Internal

Internally, banks are a relatively clean sector. The environme...