![]()

1 ‘A far greater Genius than Sir Joshua’: some issues and complexities around the portraiture1

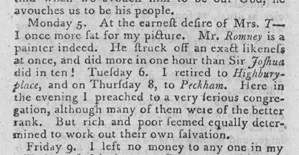

A disparaging comment in John Wesley’s Journal about Joshua Reynolds (1723–92) the leading portrait artist of the eighteenth century and the influential founding President of the Royal Academy, has fuelled recurrent speculation about whether, and when, Reynolds painted Wesley and, if so, what has become of the portrait – and why no prints are known. In his published Journal for 5 January 1789, sitting to George Romney, Wesley wrote:

At the earnest desire of Mrs. T[ighe], I once more sat for my picture. Mr. Romney is a painter indeed. He struck off an exact likeness at once, and did more in one hour than Sir Joshua did in ten.2

Nearly two decades earlier, in 1771, Wesley had written to Henry Brooke (1738–1806), a Methodist and artist in Dublin:

Mr. Williams (a man unknown) is a far greater Genius than Sr. Joshua. He took a better Likeness of me in Ten Minutes than the other did in Twenty Hours.3

In both of these two ill-disposed references, Wesley inferred that he was painted by Joshua Reynolds; that Reynolds’s work was slow and thus he failed to capture a reasonable likeness.

This chapter seeks to suggest a plausible solution to the whole matter and set it within the context of the eighteenth-century portrait business. Since the route to doing so leads into considerations of the nature of artistic practice at the time as well as of the processes behind some of the written sources, it also serves as a useful introduction to some of the issues and complexities around a serious iconographical evaluation of John Wesley.

Wesley’s Journal, on which much immediate evidence hinges, was published in his lifetime, although as we shall see, it is far from being a straightforward account of his day-to-day life. The question of a Reynolds portrait seems first to have arisen in 1840 in a letter to Jabez Bunting about the possible purchase of some Wesley family portraits, including ‘Rev. J. Wesley, by Sir Joshua Reynolds, half-length, life size, age about 40’.4 However, after some time it was recognised that the ‘Reynolds’ was in fact a copy of the Williams, by Harley.

Figure 1.1 John Wesley, Journal, January 1789

Down the years, time and energy continued to be expended at various points and by a number of people on this question. At the 1899 Wesleyan Conference (the annual national gathering of the largest British Methodist denomination) a portrait was publicly exhibited in some triumph as the long-lost Reynolds picture, only for that to be fairly rapidly challenged and re-identified as in fact a painting of John Cennick (1718–55), one of Wesley’s young preachers and later a Moravian minister.5

Joseph Wright, characteristically, dealt with the matter sympathetically but objectively, concluding that, had such a picture ever existed (for which there was little evidence), it was probably destroyed in a fire at Dangan Castle, Ireland, the former home of a branch of the Wellesley family.6 The Wesleys were related to the Wellesley family: the Duke of Wellington was Arthur Wesley but altered his surname while serving in India.7 Ellis Waterhouse, following Graves and Cronin,8 noted a picture thought to be of Wesley by Reynolds, but also identified as Garret Wesley (1735–84), 1st Earl of Mornington.9

Another suggestion was that Reynolds had produced a secret picture of Wesley in 1789, around the same time as Romney’s portrait, which had been used after his death as the ‘official likeness’ and from which John Barry had taken a miniature. The portrait, it posited, had been kept hidden for nearly a century and a half. The convoluted reasoning behind this intriguing theory makes for curious reading, attempting as it does to explain away the lack (or peripheral survival) of almost all evidence as indicative of its success. In 1935 Wesley’s 1771 letter to Brooke was published, which by its date disposes of this fanciful theory.10

On Reynolds’s side are seven entries in his ‘Pocket Book’ for 1755 (the earliest to survive) for a ‘Mr. Westly’:11

Sat. 8th March, 10

Tue. 11th March, 9

Thur. 13th March, 9

Sat. 15th March, 9

Wed. 19th March, 9 (cancelled)

Mon. 30 June, 9

Mon. 7 July, 9

Yet no painted canvas has ever been traced which can plausibly be attributed to Reynolds, nor a related print.

At face value the documentary sources may seem, if not conclusive, strongly indicative that Wesley did sit to Reynolds. Studio practice might usually involve the sitter having an initial appointment to determine matters such as the size of portrait, the pose, costume to be worn and dates for subsequent appointments, followed by four sittings of (usually) two hours to paint the head in the first, followed by clothing, drapery or scenery.12 In 1777, Reynolds stated that ‘three sittings of an hour and a half are usually necessary’, although by that period his studio practice may have changed. Subsequently there would be an interval for the picture to dry, be varnished and framed, before it was ready for delivery.13 Reynolds’s dates indicate that pattern.14

Reynolds offered five sizes from a ‘head’ (24½” x 18½”) to a ‘whole length’ (94” x 58”), at ‘12 guineas for a head, 24 for a half-length and 48 for a full-length’ in the mid-1750s.15 Wesley seldom seems to have had less than a half-length portrait taken so it might be surmised that several sittings would be required, possibly involving Reynolds’s assistant painters to deal with costume, drapery or scenery. Entirely conjecturally, a compositional comparison might be made with another clerical portrait by Reynolds: of his uncle John Reynolds (1757), who is shown three-quarter length, seated.16 It is less likely of Laurence Sterne (1760) which is only recorded as taking four sessions, but the intensity of the figure is emphasised by a relatively plain background so it may be that the scenery painting was minimised – Reynolds was evidently keen to get an engraving on sale while Sterne was the talk of the town.17

David Mannings has drawn attention to some of the ambiguities and complexities surrounding Reynolds’s ‘Pocket Books’. These pre-printed notebooks, The New Memorandum Book Improv’d: or, the Gentleman and Tradesman’s Daily Pocket Journal, combined the functions of a diary and account book. They were apparently used by Reynolds for a multiplicity of purposes; to list sitters, callers or other appointments or as reminders of tasks to be done. Moreover, comparison with other sources such as contemporary correspondence, including Reynolds’s own, shows that they are neither comprehensive nor always accurate.

The student of Reynolds’s pocket books must try to distinguish between timed entries, memoranda, lists and apparently random jottings, paying attention to the evidence provided by times of the day and how entries are arranged on the page, and try to relate this material to appropriate external factors such as the framing and hanging of pictures.18

Further, entries for a ‘Mr. Westly’ may not refer to John Wesley at all, and it should be noted that there are no known paintings in the Reynolds canon of identified works for either spelling of the name.19 The Wesley family was larger than the progeny of the Epworth household.20 Like Reynolds, they emanated from the West of England, and the Wesley forebears’ name was at times spelt ‘Westly’ or ‘Westley’.21 So in an age of variant spellings, Reynolds may simply have jotted down a more familiar wording.

Wesley’s published Journal, his diaries, ‘sermon register’ and letters generally form key sources not only for his life, but also, since they are considerable and wide-ranging, for a host of other contemporary matters. However, neither are these as straightforward as might be assumed. His correspondence varied from terse, mundane, personal communications to lengthy disquisitions which might appear in the press while his sermon register was simply his own record of when and where he had preached, and the texts he had taken.

His diaries and Journal are less straightforward. From being a young man at Oxford, John Wesley started to keep a regular diary (as well as his personal monetary accounts), noting in detail his daily activities. These were written in his own adaptation of John Byrom’s shorthand which defied full reading until Prof. Richard Heitzenrater was able to decrypt them in the 1970s. Although a number of scholars can now decode the shorthand, there continues to remain an element of uncertainty about the absolute accuracy of some readings.22

Then from the late 1730s Wesley co...