- 228 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Kuwait: Prospect and Reality

About this book

For many the story of this small Arabian state begins and ends with the wealth that has accrued from its vast oil deposits. But the real fascination of Kuwait lies in its geological and archaeological history; in its long struggle for survival among powerful neighbours; in its ambitious plans for industrial and economic development. This book, first published in 1972, shows the effects of the new material wealth opened up by oil in relation to the country's remote past and its Islamic background.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1. The Sands of Time

By geological standards, those events which had the profoundest influence on the territory of Kuwait took place in comparatively recent times - between 130 million and 70 million years ago. The mesozoic era, during which most of the world’s great oil deposits were formed, stretches back 225 million years to the time when the earliest known reptiles appeared. It came to an end about 70 million years ago with the extinction of unimaginable hordes of the most monstrous creatures ever to inhabit the earth. That era embraced the triassic, Jurassic and cretaceous periods, and it was during the last of these, in a time span of about 60 million years, that the foundation of Kuwait’s vast oil deposit was laid. Then, according to the fossil evidence preserved in rocks, large areas were covered by vegetation and dominated by giant reptiles such as the ichthyosaurus, immense lizards and serpent-like creatures. Forests, swamps and seas teemed with animal and vegetable life. The seas flowed over the land, across the plains of Arabia, lapping up to the hills of the north, the west and the south. Then, after further long intervals, the seas ebbed. In this alternating advance and withdrawal of the sea vast quantities of plant life were both generated and destroyed. It is known that an ice age occurred in the cretaceous interval of time. A vast blanket of ice advanced across much of the world, from Europe to farthest Asia, and then gradually retreated. It may have been such a layer of ice which finally engulfed the last of the giant reptiles, for by the end of the cretaceous period they were extinct. Embedded in chalk and rock, they decomposed along with a squelching mass of plants and smaller creatures, the organic basis of the oil hydrocarbons to which intense heat and immense pressures reduced them over ensuing millions of years.

A sketchy explanation. But necessarily so, for the processes of natural change occurring over hundreds of millions of years do not resolve themselves simply or lend themselves to easy scrutiny. Much remains conjectural. The most that the geologist or the palaeontologist will commit himself to is the proposition that a transformation of the complex organic chemistry of life into simpler hydrocarbon forms, over immense periods of time and at great temperatures and pressures, is as plausible an explanation as can be advanced for the existence of oil. At any rate, it is an academic question. The liquid bounty is there, and for the Arab that is a matter more for gratitude than for argument as to why and wherefrom.

The evidence of depth and of rock formation suggests that much of Arabia’s oil was, in fact, formed at different periods of the earth’s formative upheaval. The plains of the great peninsula - framed by the land masses of Lebanon and Syria in the north, and by the highlands of the south and west - form an immense structural basin in which changing patterns of climate and life were able to interact and ultimately to produce some of the richest of all the world’s oil deposits. Before the cretaceous period, even before the mesozoic era, in the so-called paleozoic segment of time which ranged over something like 350 million years, the same coming and going of seas and ice blankets, the alternating intervals of life generation and life extinction, took place. And, thus, by the transformation of unimaginable quantities of plant and animal life, oil was produced at other levels. These processes also went on after the main Kuwait deposits had been formed, into the eocene and miocene periods of the more recent tertiary or cenozoic era. From Iran and Iraq, down to the Gulf regions of Kuwait, Bahrain, and Qatar, beyond to Oman and Dhufar, landwards to eastern Saudi Arabia, oil-bearing sands and rocks testify to a passage of time which all but defies human comprehension, and to events whose major significance has been concealed from mankind, as though by an ingenious conspiracy of nature, until its moment of need.

By comparison with the geologist’s time scale, the history of man is short measure. Nevertheless, the earliest inhabitants of Arabia probably occupied a land far removed in structure and climate from its present form - green and deciduous, well-watered and teeming with animal and plant life. Again, supposition must take the place of evidence. Curiously, less is known of man’s earliest years on earth, than of the millions of years which preceded him. He left nothing so useful by way of evidence as the fossils, the encrusted plants, bones and molluscs, which enable the palaeontologist to make at least an inspired guess at time and circumstance. Arabia was probably on the edge of that last great ice sheet which covered much of Europe, Asia and America for nearly three million years, and which finally petered out some 11,000 years ago. As the ice advanced and retreated, perhaps four times during that expanse of time, grassland changed gradually to desert, running streams to dry wadis. The transition was slow, but in the end it gave rise to conditions of climate and terrain which are at the root of the Arab character, at once catalyst and inhibiting force in a remarkable historical development. To say that the Kuwaiti is an Arab and that his country’s history is an integral part of Arabia’s, coloured perhaps by a long association with the sea and maritime tradition, is to state the essential facts of the matter. But it begs a great many questions. We know, or at any rate can deduce, much that occurred in the vast desert expanse of the Najd and Hejaz over the 1,300 years or so since the dawn of Islam. But what of the millennia of human occupation before? What of the thousands of years between the first communities of the peninsula and the enlightenment; between the common ancestor of these peoples, Shem, son of Noah, and the Prophet Muhammad? And what of the even more dimly lit regions of the stone and iron ages? Frankly, we know little, though chinks of light have penetrated the darkness in recent times. For the rest we must fill the gaps in our knowledge as best we can by reference to the earliest communities and civilisations along the edge of the desert. Though the nomadic Arabs of the interior gave much to the places in which they settled and to the people they mixed with, they have left no tangible evidence of their own distant past.

The tens of thousands of years which separated the primitive tribes of the Arabian peninsula from the men who first learned the rudiments of the languages we came to call Semitic, are recorded by nothing more substantial than a question mark. It can reasonably be assumed that after the formation of the last great mountain ranges in Europe and Asia Minor, and after the glaciers had melted away, the earliest inhabitants of central Arabia roamed a wet and marshy territory, armed with the crudest implements of wood or stone. As the area became drier and almost bereft of plant life, these people must have gradually turned their thoughts and implements to husbandry of the soil and the herding of animals, learned to seek out the land most able to support crops and to cultivate it; to breed and shepherd flocks; to fashion more efficient instruments for work, and doubtless for war. Like other formative races of mankind, they began to produce basic linguistic forms. Some settled where there was water and sustenance. Others kept up a nomadic existence, taking their herds and their flocks with them. While most if not all other inhabited parts of the world remained in a state of savagery, settled communities formed in the basins of the Tigris and the Euphrates and it was there, especially towards the convergence of those rivers in the southern lowlands of Mesopotamia, that civilisation first began to take shape. Abraham was born 2,000 years before Christ, yet his birthplace Ur had seen near miracles of construction and civilised achievement during a thousand years before that. It was the Sumerians beyond the northern extremity of the Gulf who invented writing and gave the first real impetus to the advancement of mankind. Inland at Ur, Erech, Lagash and Nippur, and at Eridu near the coast, they developed the arts of pottery and sculpture, of architecture and vehicle design; they plotted the heavens and devised the first principles of astrology; they developed the sexagesimal method of numbering which survives today in the division of the hour into 60 minutes and the minute into 60 seconds, and in the geometric division of the circle into 360 degrees; they learned to irrigate the land; and while all this was going on the cities of Sumer fought pitched battles with each other. They exemplified at the very moment of man’s emergence from primitive into civilised social organisation, the perversity that has dogged his progress ever since, the almost interdependent abilities to create and destroy, the limitless contradiction of a capacity to love and to hate in about equal measure. The Sumerians recorded their findings, their conflicts, their dead - and the names of the royal servants they buried alive so that they could continue to serve their kings in the life after - in cuneiform script on tablets of clay. Thus, archaeologists have been able to piece together a well documented account of this fertile strip of land from which some of the most majestic achievements of civilisation derive. To the north of Sumer, Semitic groups who long before had come as nomadic tribesmen from the Arabian desert, formed the kingdoms of Kish and Mari. Under the leadership of Sargon, they spread their dominion over an area from Elam, east of Sumer, to the Mediterranean Sea.

The Empire of Akkad embraced the whole of the region that was to become Babylonia, and much of Assyria. It was, in fact, the first empire of history and it almost certainly stretched as far as the area of the Gulf to the south of the valley of the Tigris and Euphrates. It was a relatively benevolent imperial power, for when the authority of the Akkadians declined it gave way to the combined rule of Sumer and Akkad, to a Sumerian culture regenerated by Semitic influence. By 1900 bc, another Semitic people-the Amorites-had taken over Babylonia and ousted from power the Akkadians and Sumerians, who nonetheless remained a powerful force in the area. Under the Amorite king Hammurabi, the regions of Assyria, Akkad, Babylonia and Chaldea, from beyond Nineveh in the north to the coastal tip of the Gulf in the south, became thriving centres of learning. They systema-tised the legal codes built up over several centuries by the Semites and Sumerians, and developed the arts and sciences through a virtually uninterrupted period of two centuries.

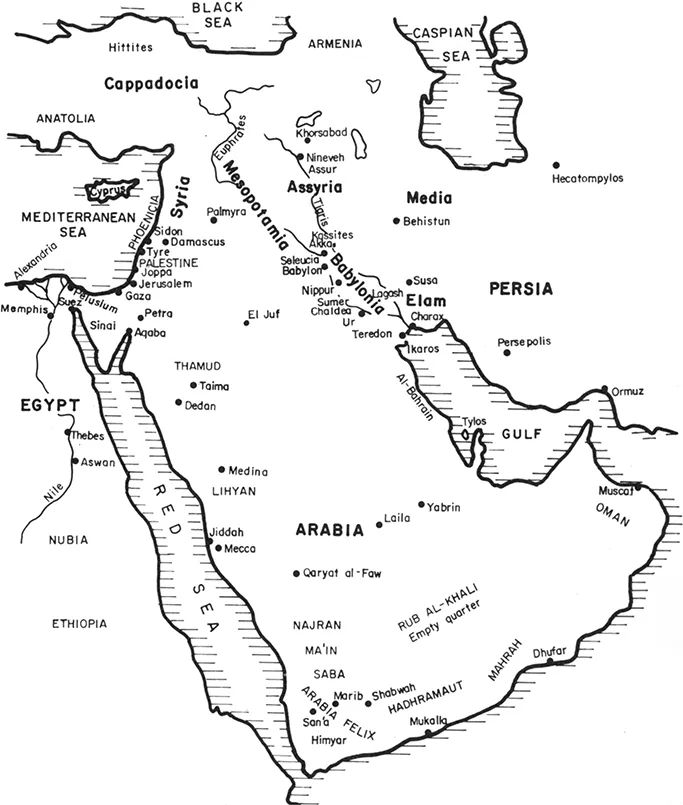

ii Ancient civilisations and places

Then came the Hittites. Descending the Euphrates from Asia Minor, they occupied Assyria and Babylonia, thus resolving a conflict which raged almost without pause between the kings of those nations. Eventually the Hittites’ influence spread across northern Arabia to the Mediterranean. They captured northern Syria and concluded a series of non-aggression treaties with the Egyptians, though neither party was thereby inhibited from attacking the other when opportunity offered. There was a constant flux of invasion and counter-invasion across the fertile plains of Assyria and Babylonia. By 1750 bc the Kassites from the region of Elam had established the third dynasty of Babylon, their kings ruling for 576 years. In 1175bc Nebuchadnezzar came to power to face continuing conflict with Assyria and a new onslaught from the Arameans. For another 500 years, with only brief periods of respite, Babylon was weakened by invasion and internal dissension, prey to the Assyrians, Arameans and Elamites. Meanwhile, Assyria became revitalised and, combining a culture derived from Babylon with a natural instinct for commerce and combat, spread learning, trade and disarray throughout the Middle East. They deported entire conquered tribes by way of upholding their rule. Yet they also created some of the finest buildings of the ancient world and, at their capital of Nineveh, built up the most famous library of antiquity. When Assurbanipal, the last great king of Assyria, had completed his campaigns agains Egypt, Elam and Babylon between 668 and 626 bc, the energies of his empire were exhausted. It was eventually brought to ruin and divided by the re-emergent Babylonians and Medes.

The Chaldeans, people of Arabic and Aramean stock, had begun to appear in Southern Babylon in about 1000 bc. They were a constant thorn in the side of Assyrian conquerers and it was under their influence, and under the leadership of Nebuchadnezzar II, that the neo-Babylonian Empire was established, bringing a new if brief splendour to the region marked by the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates. The sacred date tree flourished in fertile, well-irrigated plains, the hanging gardens and the great walls were built, astronomy and the mathematical sciences were given a new lease of life. But Chaldean Babylon learned no more of the art of conserving its energies by peaceful deployment than did its predecessors or successors. It destroyed Jerusalem and its army even crossed over to Egypt.

When Nebuchadnezzar died, Babylonia began its final decline. Under Nabonidus, it fell to the Persian army under Cyrus without protest, its intellectual and material splendours gradually fading under the successive rule of Persian, Greek, Parthian and Sassanid, until the Arab caliphate established in ad 636. Such were the fortunes and achievements of the people of the arc which sweeps upward and across from Gulf to Egypt. While they held sway, creativity and scholarship thrived.

The cross-currents of dominion and language and custom in these fertile lands gave rise to immense intellectual and material progress. We know little of what went before. When archaeologists began to uncover the evidence of habitations of 4,000 years or more ago, there were few links with the prehistoric past. Unlike Egypt, where flint implements and metallic objects traced an evolutionary path from primitive bush life, through a neolithic period to the first dynasties, the ancient sites of Sumerian and Semitic occupation revealed few such traces. It must be assumed that most examples of palaeolithic or neolithic workmanship were removed by flood from the delta region of the Tigris and Euphrates, before the first cities were built and the land reclaimed. Recent archaeological discoveries of the greatest importance in the region of the Gulf make up for much of that deficiency in our knowledge, but more of them later.

If the progression from prehistoric to historic man has for long been obscure, more recent developments along the periphery of Arabia are well and truly recorded, or at any rate implied, in the documents of the three great religions which have their origins in the Semitic lands. Community life and trade prospered for three thousand years before Christ in the crescent area which began just below the place that is now Basra at the tip of the Gulf, traced an arc through Babylonia, Assyria, Phoenicia, Syria and Palestine, and terminated at Aqaba in the west. Settled communities also formed along the highlands that skirt the Red Sea, from Jiddah to South Arabia, and along the Arabian Sea coastline to Dhufar. Trade routes brought the inhabitants of these distant places into contact with each other and with people of the desert.

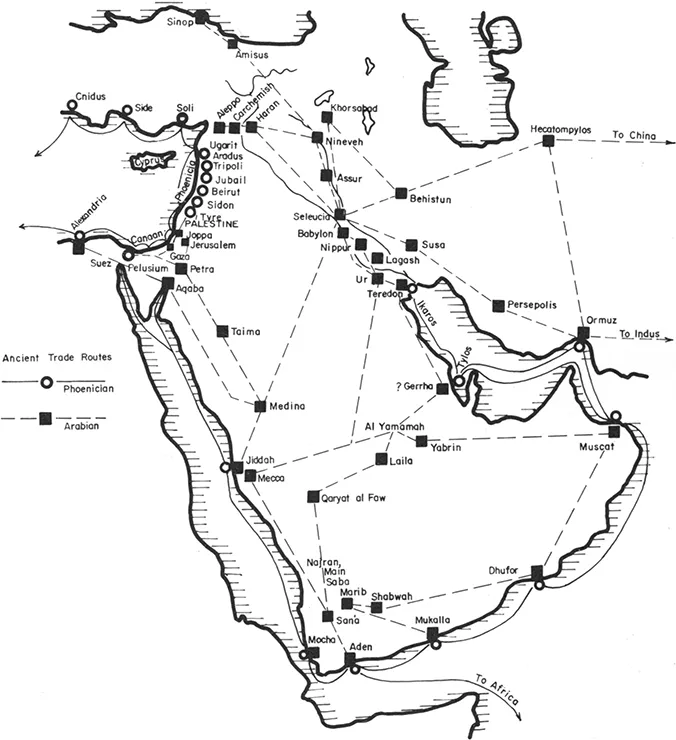

iii Ancient Trade Routes

The overspill from the deserts regularly invaded the settled areas whose less warlike people fell easy victims to the nomads. The influx of such tribesmen into the settled areas infused them with new blood and new virility. Sometimes they simply bartered their wares of livestock or fur, skins, silk, wool, spices, ivory, frankincense, myrrh or fuel, and returned from whence they came. From Marib, Mukalla, Dhufar and other southern places, from Muscat, Mecca, Hufuf and Al Yamamah, the caravans of trade made their way along the coast or across the desert. Baghdad, Hail, Basra and Medina were the staging posts on the roads to Samarkand, Carchemish, Damascus, Joppa, Jerusalem, Alexandria and Petra. Their goods found markets in Cappadocia and the Hittite cities of Sinop and Amisus on the Black Sea; in Persia and along the Caspian seaboard, even in China. The people of Arabia went to Suez and into Egypt, across land and sea to Ethiopia, India and Byzantium. Their influence on the people around them was widespread and lasting. When they embraced the faith of Islam, that influence took on a new dimension. Impelled by a zealous trading instinct and given impetus by the words of the Prophet, they conquered a large part of the world, in spirit and in deed. But though the Arab has always been extrovert in his trading habits and in his determination to spread the teaching of the Prophet, he is in the very basic sense of national character, inward-looking. The people of the Arabian peninsula have retained a remarkable identity of speech and literature, and nowhere has the purity of their language been so well preserved as in the desert. In the thousands of years during which coastal Arabs have been in communication with the world at large, corrupting their speech and the written word as all languages are corrupted by trade and the domination of foreign powers, the Arab of the hinterland has kept his customs and his tongue remarkably intact; and when it has become necessary he has revitalised the habits of the townspeople on the periphery. If the term Semite is but the approximation of a German scholar in defining a race, it serves well enough. The descendants of the biblical Shem are, with all their differences, more alike in essential qualities than any other people of comparable dissemination, save perhaps the Chinese.

2. In Search of a Lost Past

We arrive at a point of diversion; a point at which much that has gone before must be qualified, or even contradicted.

The emergence of the first civilised communities in the region of Mesopotamia is no matter for conjecture. The cuneiform tablets of Babylon and Assyria, buried for 3,000 years and more, have been excavated and examined (though several thousand have yet to be translated), and made to divulge legends and historical facts from which a vast body of knowledge has been derived. In the absence of material evidence of older or even contemporary habitations, the great cities of antiquity which arose along the rivers Tigris and Euphrates, along with those of the Nile Valley, have become the accepted birthplaces of civilisation. But were they?

In 1953, a Danish archaeological expedition began an investigation in the area of the Gulf which, after fifteen years of patient digging and sifting, began to throw a startling new light on the discoveries and conclusions of the previous century, and to involve its founders in major questions of scholarship. Much of the evidence produced by the digs of this Danish team has been published by Geoffrey Bibby, an Englishman who joined the Danes as field director of the expedition, in his book Looking for Dilmun.

Looking for Dilmun meant, in fact, looking for a lost community—perhaps a mythical one. And like all such ventures it appealed more to those who wished to embark on it than to the institutions asked to provide the money. Lost civilisations represent a popular cause among enthusiasts and adventurers, but they seldom appeal to universities, oil companies or governments. Thus, the expedition led by Professor Peter Vilhelm Glob, head of the Danish National Museum, concealed its real, if somewhat nebulous, ambitions beneath a plausible cloak. They were, they said, going to look around the famous burial mounds of Bahrain, to search for clues that might lead to something in the graves that cover much of the island like overgrown anthills and which, over the centuries, have invited much curiosity.

They were armed with some intriguing facts and even more intriguing theories.

In 1925, at about the time that Sir Leonard Woolley and Sir Flinders Petrie were digging at Ur and Babylon and Nineveh, Ernest ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half title

- title

- copy

- Apologia

- Introduction

- Contents

- 1 The Sands of Time

- 2 In Search of a Lost Past

- 3 The Islamic Heritage

- 4 Mubarak the Great

- 5 Time of Trouble

- 6 Talking of Oil

- 7 Harvest of the Desert

- 8 Politics and Economics

- 9 Looking to the Future

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Kuwait: Prospect and Reality by H.V.F. Winstone,Zahra Freeth in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Regional Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.