![]()

p.13

Part I

Pater’s Modern Involvement

New Editorial and Biographical Approaches

![]()

p.15

1 Walter Pater and the New Media

The “Child” in the House

Laurel Brake

In that half-spiritualized house he could watch the better, over again, the gradual expansion of the soul which had come to be there – of which indeed, through the law which makes the material objects about them so large an element in children’s lives, it had actually become a part; inward and outward being woven through and through each other into one inextricable texture.

(Pater, “Child in the House,” 1878, 173)

How insignificant, at the moment, seem the influences of the sensible things which are tossed and fall and lie about us, so, or so, in the environment of early childhood. How indelibly, as we afterwards discover, they affect us; with what capricious attractions and associations they figure themselves on the white paper, the smooth wax, of our ingenuous souls. . . . The realities and passions, the rumours of the greater world without, steal in upon us, each by its own little passage-way.

(177)

Introduction

Walter Pater’s writing career and the trajectory, locations, and character of his publications relate to the media of his day. Apart from Marius the Epicurean, nearly all of Pater’s writing appears in the press, only a third of which he collected in his lifetime into books. Pater’s periodical writing coincides with the emergence of the new media of his generation in the 1860s. The date of his first submission to the press in 1864–1865 coincides with the advent of the “new media” of the 1860s – new monthly magazines in 1859–1860 and reviews in 1865, and with few exceptions, his subsequent work appears in them, until his last submission in 1894. In this sense Pater is a “child” in the “house” of publishing, an equivalent of “born digital” in our own period of print in transition.

Lisa Gitelman and Geoffrey Pingree are helpful here in “What’s New about New Media” (2003), where they argue “All media was once ‘new media’” (xi). In demonstrating their case, they focus on transitional moments of media change:

p.16

(xii)

The new media in the nineteenth century consist of the revised forms of the newspaper, magazine, and review genres that follow the repeal of the newspaper taxes 1855–1861, in which Walter Pater’s writing appeared for nearly thirty years. For that reason, his journalism cannot be explained as an “apprenticeship,” or “pre-literary,” as his adherence to the press spanned the entirety of his career, as it did for many of his generation.1 He is moreover one of many “university men” who wrote regularly for the press in this period.

I will argue that the pattern of Pater’s publications exhibits a catholicity – akin to what Gitelman and Pingree call “an identity crisis” – characteristic of the “uncertain status” of new media in relation to “established known media and their functions” (xii). Gitelman and Pingree detect a high incidence of intertextuality between the old media and the new, which we see in Pater’s career. On the one hand, Pater’s publishing record shows him alert to the possibilities of the new media, and an active agent in exploring them. As may be seen in the publishing patterns below, he publishes across the press, from daily newspapers to quarterlies; he adopts anonymity and signature; his press work is consistently marked by orientation to the specific journals in which it appears, but professional: he does bread-and-butter reviewing, sometimes anonymously; he puffs the work of friends, and in turn solicits their puffs of his own work; he also reviews books of interest to him, and publishes short fiction (a genre coming into its own in Britain at this time) and a novel in magazine instalments; he intervenes in contemporary critical debates, placing his criticism in high-culture magazines, reviews, and newspapers; he publishes his lectures; and he draws heavily on his journalism to compose books.

On the other hand, there is a fault line between this pattern of Pater’s in the new media and the old media, the “identity crisis” if you will, between the press and books, journalism and literature. It is there in the small fraction of his press work he reprints in his books – less than a third. This pattern of cautious selection is echoed by C.L. Shadwell, the primary editor of the posthumous editions of Pater’s works, who publishes less than half of the articles that remained uncollected. Two representations of Pater’s identity are etched in the publishing practices of the day, that of an author/artist of a “choice” number of finely honed books above the affray, and that of a working “man of letters,” who was a frequent contributor to the new media, a university lecturer, a novelist and author of books that reflect this richesse.

p.17

How did Pater navigate the shoals of this new form of journalism, and move between lectures, periodical articles, book publication, and celebrity? The patterns of his contributions to the press – titles and genres he favored, and when – are represented in the tables that follow. I also note serials to which he was invited to contribute but did not, to explore the limits of his participation in the new media – for example, in his lack of contributions to the avant-garde and the popular press.2 Much of Pater’s journalism also routinely circulated in the American press in its “eclectics” or reprint magazines. This presence of his writing in the American press during his lifetime provides a new perspective on the posthumous reprints of Pater’s work in the U.S. by Thomas Mosher – in the Bibelot, and in his fine editions.3 His work was already familiar to American readers of the press, as well as the American editions of his books published in the U.S. by Macmillan. In Pater’s last decade, post Marius the Epicurean, the character of his criticism and fiction, for example, “Style,” the Imaginary Portraits, and “Apollo in Picardy,” and where he publishes – in the New Review (1889), Harper’s (a “decadence” issue), and the Bookman (1891), register an acknowledgment of the fading force of the twenty-years-old new media and genres, and an anticipation of and participation in the new.

Pater’s Patterns of Publication

The new media that claimed most of Pater’s press work (Tables 1.1 and 1.2) multiplied the number and prominence of the layer of upmarket titles for educated readers; these titles gave new impetus to signature and celebrity, and weakened anonymity; they provided an enlarged sector for visible, attributable, cultural, literary, political, and scientific debate, which was less attached to political parties than earlier generations of serials. They enhanced what might be called “the dignity of literature,” allowing university men to publish and debate respectably in these new organs. More generally, they offered an enlarged market for prose of all types – critical, analytical/political, expository, and fiction in article-length instalments; and not least, they provided authors with more opportunity to earn an income from writing, strengthening authorship itself. The new media of the 1860s offered greater security to freelance authors such as Pater, by facilitating the coupling of serial and book publication. In its multiplication of serial titles and readers, it made this pattern – enjoyed principally to date by authors of very successful fiction, such as Dickens – more generally accessible, whereby an author could be paid for a lecture, periodical publication, and book sales. This may be seen in 1864–1865 in the example of Matthew’s Arnold’s publication of “The Function of Criticism at the Present Time” that appeared in three media forms in rapid succession: as a lecture on October 23, 1864, as a periodical article on November 1, 1864, and in a book of collected pieces in February 1865.4

p.18

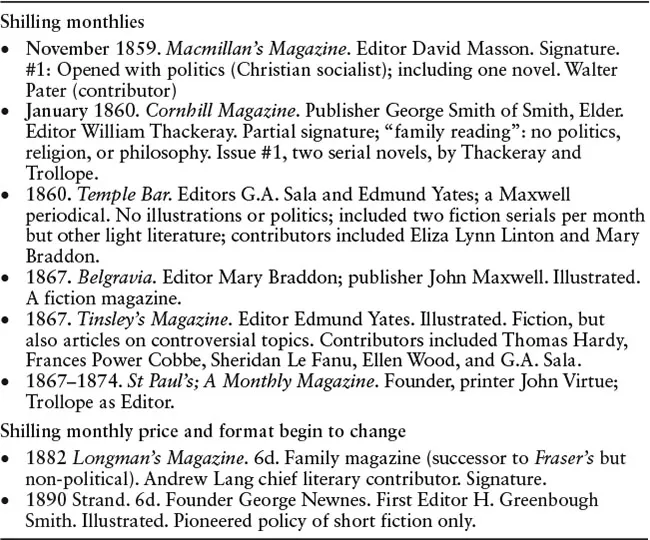

Table 1.1 Monthly magazines. New generations 1859–1890. 1 shilling; 6d

This is the “house” that Pater and his writing inhabited; its culture is discernible across his career and his diverse publications, in which anonymity, signature, critical prose, magazine fiction, the dignity of literature, celebrity, and the need for income from his writing all figure. These characteristics, especially signature, were limited to the new periodical press rather than the press as a whole, but traces are discernible in early new journalism newspapers such as the daily Pall Mall Gazette. However, anonymity did survive: three of five of Pater’s pieces in the Pall Mall Gazette were anonymous, as were his nine contributions to the weekly newspaper, the Guardian. He even published two anonymous review articles in Macmillan’s Magazine in the 1880s, one of the original flagships of signature in the 1860s.

p.19

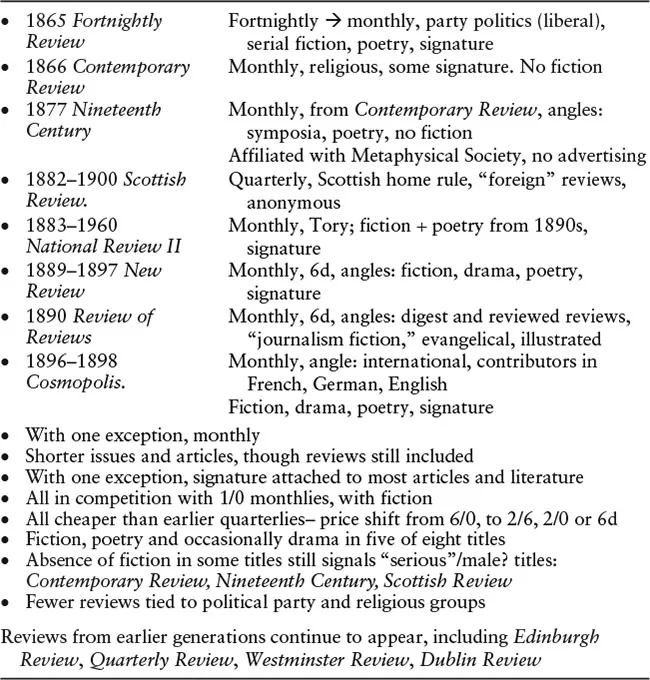

Table 1.2 New (fourth) generation of reviews 1865–1898

To summarize, the contents of the new generation of monthlies (magazines and reviews) and some weekly newspapers represented a fresh market for authors for lighter, shorter, brighter pieces distinct from those solicited for the quarterly reviews or older monthlies, and untied to political editors and parties, like the Edinburgh, the Quarterly, Blackwood’s, and Fraser’s. They multiplied significantly the periodical market for fiction, giving a fillip to magazine fiction, beyond, for example, Blackwood’s Magazine and All the Year Round, and to criticism. At the cheaper price of a shilling, or 2/0 or 2/6 for reviews, the consumer base and readership for both journals and books were widened and augmented, as well as the author base. The new generation of magazines, reviews, and weeklies tightened the bond between literature and journalism, providing a larger platform for “criticism.” It also furthered the release of the serial novel from the standalone form of part-issue, housing it in the protective and high-circulation envelope of a branded periodical, imitating and consolidating the practice of Dickens and Blackwood in their magazines. Pater’s writing for the press bears the marks of these changed conditions of writing in the new media.

Nor was Pater’s presence in the new media confined to his contributions to serial titles. Searches of the corpus of the tiny percentage of digitized British newspapers and periodicals to which we now have access indicate that Pater was all over the U.K. press, as the subject of book reviews, literary gossip, and announcements, from tiny papers in Scotland, to titles in Ireland and Yorkshire, to the metropolitan press.5 In Robert Seiler’s pioneering Critical Heritage volume in 1980, we had an indication of coverage of Pater in the press, but the power of publicity, networks, syndicates, and cutting and pasting in an age of celebrity emerges more clearly in this later digital manifestation of the general “circulation” of “Pater” and h...