- 148 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book, originally published in 1984 by a group of leading international commentators on the oil market and major corporate figures int eh market, investigates the underlying forces determining the oil market in the 1970s and 80s. It also discusses the important indicators which point to how the energy market was likely to develop with separate chapters on oil, coal and nuclear power.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Energy Crisis by David Hawdon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

OECD COAL DEMAND IN THE 1980s

Herman T Franssen

1. INTRODUCTION

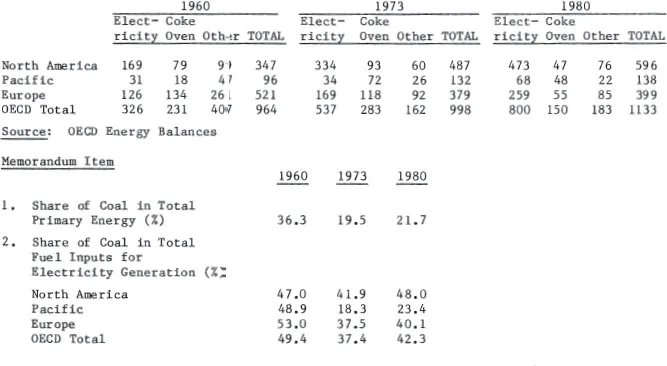

Coal played a dominant role in world energy use in the early part of this century. As late as the early Fifties when the transition to oil and gas began in earnest, coal still contributed 57% to OECD primary energy consumption. Not only was coal the principal fuel in electricity generation, as it still is in the U.S. today, but it was widely used in other sectors as well, as shown in Table 8.

Table 8

Distribution of OECD Coal Use by Major End-Users in 1950 and 1980

Distribution of OECD Coal Use by Major End-Users in 1950 and 1980

(in %)

| 1950 | 1980 | |

| Electricity | 19 | 66 |

| Coke Ovens | 20 | 22 |

| Industry | 22 | 0.5 |

| Railroads | 12 | negl. |

| Residential/Commercial | 22 | 3 |

| Conversion | 5 | 0.5 |

The rapid shift to clean oil and gas in the 1950s and 1960s quickly reduced coal’s role in all sectors but electricity and the iron and steel industry. In volumetric terms coal consumption remained stagnant in the 1960s and in fact through the late 1970s. Coal’s share of OECD energy markets however, declined from 36% of Total Primary Energy (TPE) use in 1960 to 20% in 1973. Availability of cheap and cleaner alternative to oil, handling problems, etc., all contributed to the shift away from coal. As shown in Table 1 the big decline in coal use was largely caused by declining demand for thermal use by non-electricity industries, heating use in the residential sector, and the shift of the railways to oil and electricity. This was partly offset by growth in the electricity sector, mainly in the United States.

Continuing decline in the share of coal in TPE in the 1960s caused energy analysts to state unequivocally that coal had no future in OECD energy matters. It was a dirty fuel, difficult to handle, non-competitive with fuel oil and sometimes natural gas, and required cumbersome processing and transportation to markets.

The oil shock of 1973 and more so the supply disruptions in 1979 followed by another round of price increases, changed the perceptions of the future of coal use. In the late 1970s when the perception of structural changes in energy demand had not yet become apparent, it was assumed that as quickly as possible all sources of energy in the OECD needed to be mobilised in order to reduce over-reliance on imported oil. The OECD Steam Coal report of 1978 and the famous M.I.T. Wocal study reflected the renewed optimism for future coal use. This optimism was again expressed by IEA ministers at the Venice Summit Conference of 1979, when Governments showed their determination to see to it that coal use in the IEA Countries would be doubled in the 1980s. The lengthy post-1979 recessions and possible major structural changes in heavy industries of the industrial countries have recently tempered the atmosphere of buoyant optimism on coal use of the late 1970s. Current assessments of the use of coal in the next two decades still show great promise for the “black gold” in the OECD’s future energy mix, but some of the optimism of the late 1970s has vanished. This is the result of lower economic growth expectations, expected changes in the mix of industrial output, and structural changes in energy markets.

2. COAL IN THE 1960s

Between 1960 and 1973, demand for coal remained virtually constant in the OECD area, increasing from 964 Mtce in 1960 to only 998 Mtce by 1973 (see Table 9) despite the rapid rise in TPE demand. The relative importance of coal accordingly declined from more than 36% of TPE in 1960 to less than 20% by 1973. This overall performance is explained largely by greatly reduced coal demand for thermal use by non-electricity industries and heating use in the residential sector, primarily in Europe, which OECD COAL USE BY SECTOR (Mtce) which was partly offset by growth in the electricity sector, mainly in the United States. Reflecting the steady growth of the iron and steel industry in the OECD in the 1960s, metallurgical coal use for coke ovens showed a modest increase of 1.6% a year from 231 Mtce to 283 Mtce.

TABLE 9

OECD COAL USE BY SECTOR

(Mtce)

(Mtce)

Within this overall picture, there are considerable regional differences. Coal use in the electricity sector in North America virtually doubled, while growing only slightly in other regions. As a result, North America accounted for almost 50% of total OECD coal use by 1973, compared with only 36% in 1960. Coal use in the iron and steel industry declined slightly in Europe, but quadrupled in the Pacific area. Virtually all of this was due to the fast growth of the Japanese iron and steel industry. In other uses, coal declined in all OECD areas, but most dramatically in Europe.

Even in the years following the sharp oil price increases of 1973, total OECD coal demand did not grow significantly. Between 1973 and 1978, coal demand grew only at a low rate of 0.9% annually and the share of coal in TPE decreased slightly from 19.5% in 1973 to 19.2% in 1978. During this period, the demand growth of coal for electricity generation in each OECD region was partly offset by the decline in coal use for coke ovens in North America and Europe, and for the residential sector in Europe. However, the oil price increases following the Iranian revolution caused a mini-boom for coal in 1980 and the share of coal in TPE increased to 22% in 1980. Despite the slow overall growth in total demand, coal consumption for electricity generation increased at a fairly high rate of 5.1% per year since 1973, thus firmly establishing electricity generation as the dominant market for coal. It accounted for 66% of total coal use in 1980 compared with 55% in 1973. The considerable volumetric growth in coal use for electricity generation did not, however, prevent a substantial decline in the share of coal in total OECD fuel inputs for electricity generation, from almost 50% in 1960 to about 37% by 1973. In particular in Western Europe and Japan the relative importance of coal in this sector declined dramatically because of the availability of the cheaper and cleaner fuels, oil and natural gas. Even after the 1973/74 oil shock there was no significant growth in coal demand. Substantial growth in coal demand in the electricity sector (about 5%/year) was largely offset by declines in the industrial and residential/commercial sectors.

The continuous, and probably irreversible, decline in coal use in the residential sector is mainly due to the inconvenience of handling coal and the environmental problems associated with it. As for metallurgical coal, the general decline in steel output in the OECD caused demand for metallurgical coal to fall in the years after 1973. In the industrial sector, many boilers using thermal coal had been replaced by oil or gas boilers by 1973 due to the cost advantage, convenience and environmental attraction of oil and gas. Between 1973 and 1979 no big change in thermal coal use in this sector took place, but following the 1979-1980 oil price rise the cement industry switched its fuel from oil to thermal coal. There were also signs in some other energy-consuming industries of switching from oil to coal.

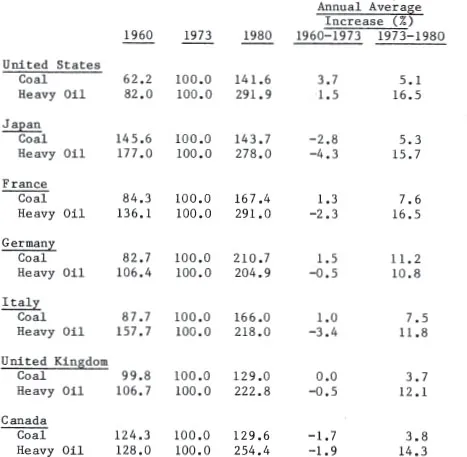

3. COAL PRICES

The distinct difference in price trends between coal and oil has been the main factor responsible for explaining the relative use of these fuels in the industrial sector and particularly for electricity generation. During 1960 and 1973, coal prices moved more slowly than oil in most of the coal consuming and producing countries, except in the United States (see Table 10). Among consuming countries, coal prices in Japan declined by about one-third between 1960 and 1973, due largely to replacement of high cost domestic coal by imported metallurgical coal. At the same time, the price of heavy fuel oil progressively declined in real terms, particularly in Japan, Italy and France. These countries had no significant domestic coal resources and consequently experienced a rapid transition from coal to oil in their industrial and residential sectors. In addition to the incentive provided by relative price movements, environmental considerations and ease of handling also promoted the shift away from coal, particularly given the less sophisticated technology available to control emissions from coal burning in the 1960s.

Following the considerable increase in oil prices after 1973, coal prices also tended to rise in all OECD countries. However the rate of increase of coal prices was markedly lower than that of oil. Coal price rise was most prominent in Germany, where coal production was increasingly made at more costly deeper seams. In other countries, however, between 1973 and 1980, real coal prices rose by only 4%-8% per year compared with an 11%-17% annual increase in real heavy fuel oil prices for industrial use. In the United States, coal prices rose by about 40% from 1973-80, while heavy fuel oil prices almost tripled over the same period. In most other OECD countries, coal prices increased much more modestly compared with industrial heavy fuel oil prices. As a result, coal’s competitive advantage increased dramatically after 1973, and this has been even further accentuated by the most recent increases in oil prices in 1979 and 1980.

TABLE 10

HISTORICAL DELIVERED COAL OIL PRICES FOR INDUSTRY

(Real Price Indices, 1973 = 100)

(Real Price Indices, 1973 = 100)

Note: Coal prices for industrial use include both thermal and metallurgical coal.

Source: Government statistics and other sources.

The price of coal increased rapidly during 1980 and 1981 due to the tight market caused by the sudden decrease of Polish exports to OECD Europe and the rapid conversion of the cement industry to coal.

4. 1979-82 DEVELOPMENTS

In the first two years following the second oil shock of 1979 coal demand grew rapidly in spite of generally declining energy consumption. Total primary energy consumption fell 2.5% per year and oil demand was reduced by 7.5% per year through l...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- The Contributors

- Introduction and Summary

- Energy Economics and Policy - Lessons from the Past. Nigel Lawson

- The Changing Energy Market: What Can We Learn from the Last Ten Years? Colin Robinson

- OPEC and the World Energy Market. Edith Penrose

- Oil Companies and the Changing Energy Market. Peter Baxendell

- The Future of Oil Supply and Demand. Morris T. Adelman

- The Future of Nuclear Power. Wolf Häfele

- Coal Production and Trade in the Future. Dr Herman T. Franssen

- The Crisis of 1983 - Panel Discussion. Ray Dafter, Walid Khadduri, Robert Mabro, Michael Parker