Towards the end of a career that spanned almost 60 years, Ivan Petrovich Pavlov, eminent Russian physiologist, member of the Royal Society and Nobel prize-winner, concluded that sleep was a relatively straightforward process characterised by ‘spreading cortical inhibition’. By this Pavlov meant that as brain cells fatigue, they switch off one by one. When enough of them have switched off the brain falls asleep.1 Conversely, as each cell becomes restored, then it switches back on and, when enough are switched on, the brain awakes. For Pavlov there was no single structure in the brain which controlled these events; the states of sleep and wakefulness were democratically selected by the cells of the cortex. While many scientists in the early decades of this century may not have agreed with the detail of this view, most shared the assumption that sleep was a fairly simple process during which individuals passed into a state of unresponsive somnolence, where they steadily remained until full consciousness returned. As all good scientists ought to be at some point in their career, Pavlov was wrong. It is now widely accepted that sleep is not only a complex, but also an active process. Far from ‘switching off, activity in the cortex (that part of the human brain responsible for so-called higher activities like thinking and solving problems) sometimes becomes quite intense even though the individual is sleeping soundly. Characteristics of sleep unrecognised by experienced scientists in the early 1920s have now become common scientific knowledge.

This improved understanding owes much to two developments which ultimately revolutionised the study of sleep. The first of these concerned the way in which sleep was quantified or measured, while the second concerned the way in which these measurements were subsequently interpreted. The significance of these two developments are probably best understood in a historical context.

The Measurement of Sleep

Traditionally, interest in sleep has been related to interest in dreams. It is unsurprising, therefore, that in the late nineteenth century interest in the nature of sleep received an indirect stimulus from the psychoanalytical movement which, under Freud, held dreams to be the rational organisation of unconscious thoughts, interpretable through analysis, and deserving of much attention. Psychoanalysts not only brought their attention to the study of dreams, they also brought their method — science. By the early years of the twentieth century what might be identified as sleep research consisted of the disparate but occasionally overlapping interests of physiologists, psychologists, psychiatrists, and others. Sleep is not a single event but at least to the researcher is myriad coordinated events and processes, any one of which may be measured and analysed. Aspects of the sleeping state selected for measurement reflected more or less the background of the researcher. Thus, while physiologists measured variations in blood pressure, temperature, heart rate and blood chemistry etc., those with a psychological bent showed a preference for the behavioural nature of sleep, for example its depth, its duration, or the effects of sleep loss on the mental state.

By the early 1930s considerable information had been accumulated concerning biological events during sleep, the periodicity or time schedule of sleep, and also the physiological and psychological consequences of sleep deprivation. Despite the large amount of information produced it was clear to some researchers that something was missing. Simply put, between sleep as described by the scientists, and sleep as experienced by the individual, there existed a credibility gap. At the level of human experience, sleep is not assessed in terms of fluctuations in temperature, or changes in systolic blood pressure. Rather, we tend to consider sleep in terms of its duration, its depth, its restorative quality and so on. What was conspicuously absent from sleep research at this time was an adequate means for relating the objectively measured processes of sleeping to the personal experience of sleep. What was required was a measurement, or a cluster of measurements which reflected relevant physiological change, and also correlated with sleeping behaviour.

To this end, considerable attention had focused upon movement, and elaborate electro-mechanical devices had been developed for quantifying (with considerable accuracy) the frequency and duration of gross body movements during sleep. All night records of motility, or ‘actogrammes’,2 could be compared with an individual’s report of sleep quality, or could be used to contrast the sleep of one individual with that of another. Because movement in bed is frequently related to our experience of ‘restful’ or ‘restless’ sleep, actogrammes could also be used to assess, in a meaningful way, the effects of sedative drugs on sleep. This would provide a clear link between the physiological effects of a drug (in terms of reduced motility) and the psychological consequences of taking the drug (in terms of more ‘restful’ sleep). While useful, the actogramme had many limitations, not least of which was its inability to record the moment at which sleep began or when it ended, neither of these events being accompanied by characteristic patterns of movement. Indeed, at this time there existed no adequate means at all for detecting when sleep onset or when waking actually occurred. Consequently, not even the most popularly used characteristic of sleep, its duration, could be determined with complete accuracy in the laboratory.

Electrical brain activity and sleep

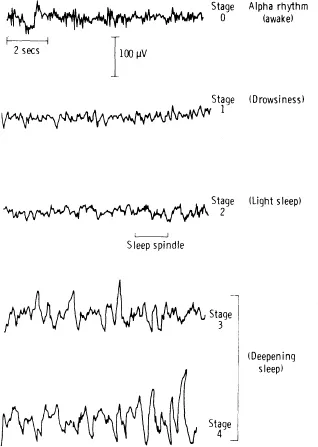

The first of the two developments which radically changed this state of affairs had, at the time, little to do with sleep research. In 1925 Hans Berger, Professor of Neurology and Psychiatry at the University of Jena in central (now East) Germany, recorded electrical brain waves from wires attached to the scalp of his young son. [Such recordings are made by a pen or stylus resting on a moving and markable surface. Amplified electrical discharges cause oscillations of the pen resulting in a trace similar in kind to those shown in Figure 1.1. In the figure the pen has moved up and down while the paper has moved from right to left.] While it had long been recognised that nerve tissue produces tiny electrical discharges when at work, these discharges had only previously been recorded from the exposed brains of animals. Professor Berger, however, was concerned to find the physiological origins of psychic phenomena in general, and telepathy in particular and, possibly for this reason, showed more interest in the activity of human brains.3 Coupled with this discovery was the further observation that the frequency and amplitude of the recorded waves could be influenced by loud noises, closing the eyes, or by concentrating, each of these events producing distinctive and recognisable wave forms. In the first report of this work published in 1929, Berger chose the term ‘Elektrenkephalogramm’ to describe his recordings. The term persists today, and the English form - electroencephalogram - is frequently reduced to the more manageable ‘EEG’.

Berger’s results were not immediately accepted by the scientific community. This (not untypical) scepticism gradually gave way as interest in the Austrian psychiatrist’s recordings grew, and further research replicated his original findings. Nevertheless, it took several years before the relevance of the EEG to the study of sleep was recognised. In 1935 Alfred L. Loomis and colleagues working in New York reported that the electroencephalogram of the sleeping human shows four quite distinct patterns which they named ‘random’, ‘saw-tooth’, ‘trains’, and ‘spindles’, depending on the appearance of the wave.4 By comparing these EEG patterns with simultaneously measured breathing rate, pulse and motility, these researchers rather cautiously concluded that ‘a change in the level of consciousness was connected with this change in type of wave.’ For example ‘trains’ were associated with settling down and falling asleep, while the slower ‘random’ activity appeared to predominate when sleep was deeper. This rather tentative conclusion, that EEG, behavioural and physiological events are synchronised during sleep provided the basis for much subsequent (and most contemporary) sleep research, and marked the beginning of the second major development which greatly influenced the study of sleep, the interpretation of the sleeping EEG.

Brain waves and the structure of sleep

The EEG appeared to provide a method capable of measuring the onset, progress, and depth of sleep. Further research by Loomis and his colleagues5 identified a total of five wave forms typical of normal human sleep which, on the whole, seemed to correlate with the sleeping individual’s level of consciousness. These wave forms, variants of the originally identified ‘random’, ‘saw-tooth’, ‘trains’, and ‘spindles’, they labelled A, B, C, D and E ‘in order of appearance [during sleep] and in order of resistance to change by disturbance [from lightest to deepest]’. It was also apparent from the EEG records that an individual did not simply descend to ‘deep’ sleep and stay there until awakened (as, for example, Pavlov had assumed), but rather, after progressing through each state of sleep from A to E, lighter sleep would return rather abruptly and the sequence would start again in cyclical fashion. In other words, levels of consciousness or awareness appeared to fall and rise again several times during the course of normal sleep.

The assumption persisted for several years that changes in the characteristics of the EEG represented qualitatively different levels of consciousness in the sleeping human with low voltage fast activity typifying light sleep, high voltage slow oscillations typifying deep sleep. Nevertheless, it was apparent to some researchers that this relationship did not always hold, and that some low voltage activity could accompany profoundly deep sleep. Prominent among the scientists who utilised the electroencephalograph for detailed studies of sleep was Dr Nathaniel Kleitman working in the Department of Physiology at the University of Chicago. In 1953 Eugene Aserinsky, a research student at the Chicago laboratory, together with Kleitman, published a brief report in the journal Science6 which not only provided a more appropriate interpretation of the all-night EEG, but also stimulated immense interest in the enterprise of sleep research.

Concerned mainly with eye-movements during sleep, Aserinsky and Kleitman had extended their EEG apparatus to include an electro-oculogram (EOG), which recorded electrical activity from plate electrodes placed above, below, and on either side of both eyes. These electrodes, very similar to those used on the scalp, are sensitive to changes in electrical potential between the cornea and the retina such as occur when the eye moves. Thus, the electro-oculogram provided a continuous record of eye movements throughout sleep. From the resulting EEG and EOG recordings, these researchers reported that, at regular intervals throughout the night, the usual slow rolling eye movements associated with sleep (and clearly visible beneath the closed lid) gave way to bursts of rapid conjugate eye movements lasting from one to several minutes. Synchronous with these bursts of rapid eye movements were low voltage, irregular brain waves — the EEG pattern characteristic of light sleep — and an increase in pulse and breathing rate. Rapid eye movement episodes occurred sometimes three, and occasionally four times each night and lasted for, on average, 20 minutes. The average interval observed between these episodes was about one and a half to two hours, this interval getting shorter as the night progressed. The feature of Aserinsky and Kleitman’s report that aroused most interest, however, was the finding that, if woken during a rapid eye movement period, individuals would more likely than not report dreaming. If woken during sleep without the rapid eye movements, individuals were unlikely to report dreaming. The observable onset and duration of rapid eye movement sleep indicated the onset and duration of the sleeper’s dream experiences.

Once again, interest in dreams stimulated interest in sleep. By the early 1960s the findings of Aserinsky and Kleitman had been replicated on numerous occasions in laboratories throughout the world. Among the conclusions drawn from these many studies was that the EEG activity associated with Rapid Eye Movement (or REM) sleep represented not just a quantitatively different level of consciousness (i.e. ‘deeper’ or lighter’ sleep), but a qualitatively different type of sleep. Following upon the work of Kleitman and his colleagues in Chicago one further characteristic of the REM state has been described which completes the now commonly used electro-physiological profile of sleep. In 1961 Ralph Berger, a sleep researcher working in the Department of Psychological Medicine at the University of Edinburgh, reported that during REM sleep the muscles of the neck show a profound degree of relaxation.7 From appropriately placed electrodes similar to those used for EEG and EOG measurements Berger had hoped to monitor any attempted speech in his sleeping subjects by recording the electrical activity in muscles (electromyograms or EMGs) over the larynx. In fact, the EMG showed a marked reduction in muscle activity consistent with relaxation immediately prior to the occurrence of rapid eye movements which was then followed on the EEG trace by the characteristic low voltage irregular brain waves. Further research showed that this relaxation associated with the REM period was also present in the trunk and limbs, and the additional measurement of muscle (usually chin muscle) activity, in combination with the electroencephalogram and the electro-oculogram, further refined the ability of researchers to distinguish between REM and non-REM sleep and has since become standard in most all-night recordings.

The Polysomnogram

In 1968 internationally agreed criteria for interpreting the ‘polysomnogram’ (i.e. the EEG, EOG, and EMG recordings made during sleep) were published.8 These criteria, incorporating the accumulated wisdom of 40 years of brain-wave recording, remain in use today, and describe five ‘stages’ of sleep. The four stages of non-REM (or NREM) sleep are identified principally on the basis of EEG appearance, and are very similar to those reported by Alfred Loomis and his colleagues in 1935, while the fifth stage, REM, is usually identified on the basis of combined EEG, EOG, and EMG activity. The EEG patterns typical of these stages are shown in Figure 1.1. Incidentally, since first being described by Aserinsky and Kleitman, REM and NREM sleep have attracted numerous epithets. REM sleep has not uncommonly been referred to as ‘paradoxical sleep’ (because the EEG suggests light sleep while the individual is, in fact, quite deeply asleep), ‘dreaming sleep’, or ‘active sleep’. NREM sleep, on the other hand, has been termed ‘orthodox sleep’ or ‘quiet sleep’. Whatever the descriptive merits of these terms, REM and NREM will be used preferentially here.

When the subject is relaxed (but with th...