![]()

1

Sixteenth-Century Bestsellers

Once only on the edges of early modern European scholarship and on the margins of maps, the Ottoman Turks have begun to be recognized as an important part of the mental world of sixteenth-century Europeans. As is the case with many kinds of otherness, when one becomes aware of them, the Turks seem to be everywhere in the period. In the first half of the sixteenth century alone, for example, over 600 books, pamphlets, ballads, and broadsheets with the Turks and/or Islam as the main subject were published in Western Europe. Throughout Europe, pamphlets reported one Ottoman victory after another. As far away as England, the ‘Turk’ was a catchword for unexpected attack and invasion. The confluence of this perceived danger with the Renaissance interest in the exotic produced a knowledge hunger that was fueled by the development of new print technology. Although it is tenuous to argue that the quantity of publication on a topic alone demonstrates the level of contemporary importance, it seems clear that sixteenth-century Europeans were fascinated with the Ottomans.1

One particularly important subgenre of this Turcica was captivity narratives. For much of Western Europe in the Late Middle Ages and Renaissance, these narratives were among the few available sources concerning life in the Ottoman Empire behind what might be termed the ‘crescent curtain.’ Apart from Venetian news reports, until the mid-sixteenth century reports from former captives provided the most extensive information.2 The wide distribution and multiple editions of these writings reflect a perennial human interest in stories about adventure, danger, and the exotic. There seems to have been something particularly intriguing about those that had been subjected to slavery and lived to tell the tale. The insider information they brought back both intrigued and scandalized their readers.3

Captivity narratives played a much greater role than simply entertainment, however. They had an enormous impact on the shaping of Western views of Islam. These ex-slaves wrote with authority. They could speak the languages of the Ottoman Empire. They had spent long years inside Turkey, seeing society in a way that, for example, a reporting itinerant traveler could not.4 Of course, the former captives did not and could not perfectly translate Turkish culture into written Latin. (Although there is much that is of interest in these writings even to historians of the Ottoman Empire.) The primary value of these writings is what they say about developing attitudes within Europe, and in particular, Western understandings of the Turks and Islam (See Figure 1.1).

In Reformation Germany two publications by former slaves of the Turks were particularly important. The Tractatus de moribus Turcarum, (c.1480) [Pamphlet on the Customs of the Turks] attributed to George of Hungary, and Bartholomew Georgijevic’ two-part publication De Turcarum ritu et caeremoniis [On the Rituals and Ceremonies of the Turks] and De afflictione tam captivorum quam etiam sub Turcae tributo viventium Christianorum [On the Afflictions of the Captive Christians Living under the Tribute of the Turks] (both 1544).5 Both of these publications were reprinted numerous times and in whole or in part were translated into several vernaculars. These two authors are especially important for three reasons. Taken together, they give significant insight into the type of information about Islam that was widely circulated in Europe during the period. In comparison with material on Islam from earlier in the medieval period, considerably more information, and more accurate information, is known. In addition, because both authors claim to have written out of the experience of Ottoman slavery and escape, these documents can add to our understanding of religious boundaries between Islam and Christianity as imagined and constructed by early modern Europeans. These texts draw boundaries in a myriad of ways, from religious practices to bathroom etiquette and food culture. Finally, although the supposed regional origins and life stories of both former captives are remarkably similar, because they were penned almost seventy years apart, a comparative reading demonstrates considerable diversity in European responses to Islam and points to important developments in Western responses to the Muslim Ottomans from the Late Middle Ages to the early modern period that highlight the important transitional nature of the period. One central focus of this study is the analysis and comparison of these two publications (See Figure 1.2).

Of course, escaped slave reports make up only a fraction of the body of Western literature about Islam and the Turks in early modern Europe. The historical confluence of Ottoman expansion and the development of widespread moveable type printing created an explosion of small booklets and broadsheets about the ‘exotic’ Turks. This production was directly tied to the military conflict with the Ottoman Empire. Some pamphlets on the Turks were published each year, but production soared during periods of more intense military confrontation, especially the 1529 siege of Vienna, the 1532 Ottoman campaign, and the 1542 annexation of Hungary. When the threat increased, general interest in the Turks increased as well.

Although nearly every land with a printing industry published “little booklets on the Turks” (in German: Türkenbüchlein) the majority were published in Italy, France, the Low Countries, and especially in Germany. During the first half of the sixteenth century alone, more than 350 pieces

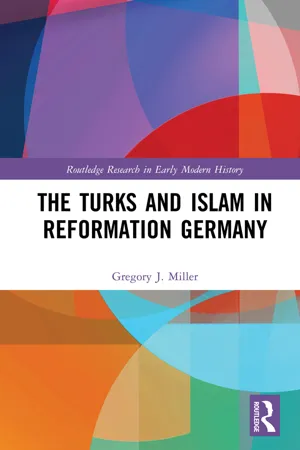

Figure 1.1 Martin Luther’s edition of George of Hungary, 1530

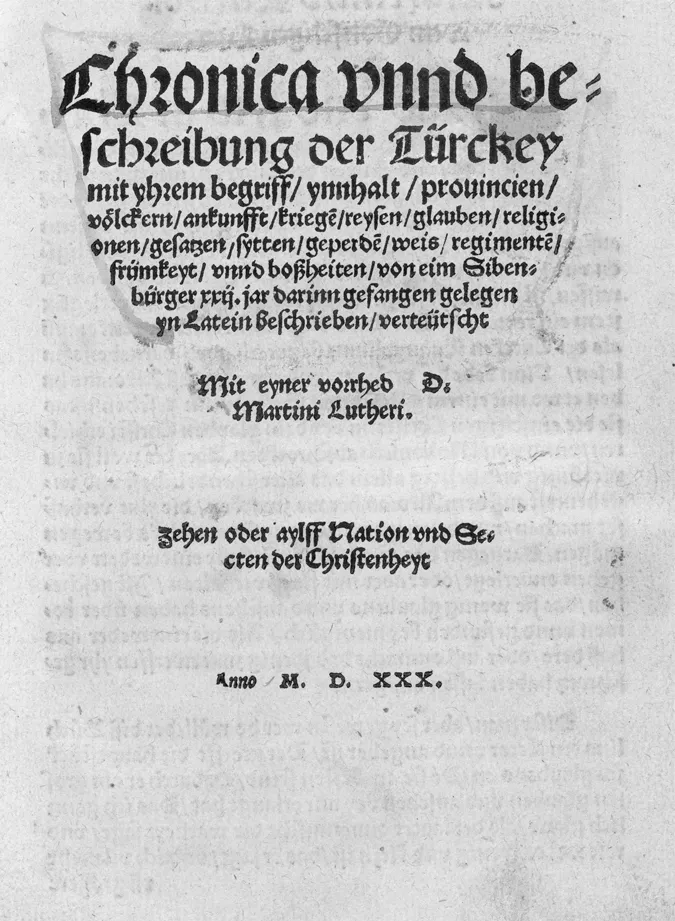

Figure 1.2 Georgijevic, De turcarum moribus, 1558

of literature specifically on the Turks were published in German-speaking lands. Very little of the significant body of sixteenth-century Turcica has been translated into English,6 despite the importance of this genre of literature in early modern Europe. This specific period is not only interesting because of the large number of publications on the Turks. It represents a high point of the Ottoman Empire’s push into Central Europe and, at the same time, a significant event in the intellectual history of Western Europe due to the development of the Protestant Reformation. From the beginning of Protestantism, understandings of the Turks and evaluations of appropriate responses to them became embroiled in confessional debates.

Interest in the Turks was not limited to any genre. All printed genre contain works on the Turks. As has been expertly analyzed by Charlotte Colding Smith, visual images, some proclaiming their basis in eyewitness accounts, were broadcast by means of single-leaf woodcuts and illustrated publications small and large.7 Secular ballads and spiritual hymns concerning the Turks were printed. Sermons and prayers against the Ottomans were published along with political speeches and Reichstag decisions. Early newspapers (in German: Neue Zeitungen) kept interested people up to date on the latest events.8 In fact, according to Andrew Pettegree, “by far the greatest stimulus to the growth of the European news industry was the relentless encroachment of the Ottoman Empire.”9

Organization of the Study

This study summarizes the views of Islam and the Turks presented in the great outpouring of literature on the Ottomans produced in German-speaking lands during the first half of the sixteenth century, that is, during the first generation of Protestant Reformers. While some of this literature originated outside of German-speaking lands, vernacular translations brought them into the German milieu and blended with the already significant number of native publications. Germans seemed to have been particularly interested in the Turks, in part due to the Hapsburg-Ottoman rivalry but also because the first generation of German Reformers (especially Martin Luther) were themselves interested in the Turks and Islam.10 In order to understand these publications, two layers of context need to be established. I begin with a short summary of the intellectual context through a survey of the development of Western attitudes toward Islam and the Turks prior to 1520. The political context is established through a summary of the engagement between the Ottomans and Europe in Reformation-era Germany.

A central contribution of this study is the content analysis of more than 300 publications from German-speaking lands that discuss the Turks and/or Islam and were printed between 1520 and 1550, that is, between the accession of Sulaiman the Magnificent and publication of the final edition of Theodor Bibliander’s Qur’an. Most of the authors of these publications make no distinction between the ‘Turks’ and Islam and often use the terms as synonyms. However, for reasons of topical analysis, I devote one chapter to descriptions of social, cultural, and military aspects of the Turks in particular. A second chapter surveys understandings of religious aspects of Islam that sometimes were applied to the Muslim world more generally.

There are two questions at the heart of most of these publications: why are the infidel Turks seemingly invincible against Christendom? What is the appropriate Christian response? The chapter ‘Holy Terror’ surveys the answers to the first question found in these pamphlets and the chapter ‘Holy War’ discusses answers to the second. Here, too, the Protestant Reformation, as seen for example both in Martin Luther’s absolute denunciation of the Crusade as a blasphemous confusion of spiritual and temporal, and in various Anabaptist disavowals of all warfare, was a catalyst for new developments that influenced the history of Christian-Islamic relations. I conclude with a more detailed comparison and contrast of the two main escaped slave narratives in the broader context of the Reformation in Germany. In appendices are found lengthy selections both of George of Hungary and Bartholomew Georgijevic. No modern English translation of either of these influential publications has previously been available. The translations have been made from their printings accompanying the first published Latin Qur’an, Theodor Bibliander’s Machumetis saracenorum principis (1543, second edition 1550). This three-volume equivalent of an ‘encyclopedia of Islam’ is the form in which these pamphlets would have been read by scholars throughout Europe during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.11 Because of their attempt to provide Europeans not only with theological and political guidance concerning the Turks but also because they attempted to portray all aspects of life and culture concerning the Ottoman, George of Hungary and Bartholomew Georgijevic provide the best short summary of the general understandings of Islam and the Turks available to Western Europeans (See Figure 1.3).

Paradigm Shifts

Over the last twenty-five years, several studies of the perceptions of the Muslim world in Western Europe have challenged th...