- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Basic Biophysics for Biology

About this book

Basic Biophysics for Biology presents the fundamental physical and chemical principles required to understand much of modern biology. The author has made extensive use of illustrations rather than a mathematical approach to establish connections between macroscopic-world models and submicroscopic phenomena. Topics covered include the nucleus, atomic and molecular structure, the principles of thermodynamics, free energy, catalysis, diffusion, and heat flow. Students and professionals in general biology, physiology, genetics, and radiation biology will appreciate this carefully prepared, non-mathematical volume.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

The Use Of Models in Science

Biophysics Is The Scientific Application Of Physics To Biology

The intent of this book is to describe some physical phenomena that are relevant to the study of biology. This kind of application of physics to other scientific fields is so widespread that whether people call themselves, say, physical chemists or molecular biophysicists sometimes boils down only to which academic department awarded them their degree.

Models Simplify Scientific Life

A biologist might be interested in a particular molecule, a beaker of solution, a cell, or a deciduous forest. Each of these is so complicated that it would be necessary to represent it by a simplified scheme or structure called a model, having fewer parts and interactions. A model is a representation, or “mental picture”, of the actual physical system and is obtained by stripping the actual system of all behavior except that which bears directly on the problem. The model can then be tested to see if it predicts any of the properties of the “real” system that it represents.

Of course, one always runs the risk of discarding important factors under the guise of simplication. This especially leads to serious problems if initial results seem to vindicate that simplification; the agreement between a model and an actual structure frequently proves to be fortuitous.

Something else we should be careful about is that by definition a model must be described in terms from our everyday, macroscopic, “real” world, and we therefore have a natural tendency to assign a “reality” to our models also. This isn’t necessarily bad — in fact it may be the only sensible approach. After all, we have only the model to work with, having decided that the original system was too complicated for direct understanding. However, we must always bear in mind that the model is a representation and the “reality” we associate with the model is going to change whenever we change the model — which we inevitably will do.

What If A Model Is Wrong?

If the philosophy of the previous three paragraphs bothers you a little, you are in the company of veterans. Any practical approach to science necessitates simplifying assumptions, but it is clear that there is often a fine line between making a problem intellectually tractable on the one hand and losing its essential nature on the other hand.

It may help to allay your uncertainties by bearing in mind that the history of scientific inquiry shows that it is useless to ask about what something “really is”. Rather, scientific inquiry generally involves the construction of better and better model representations. Each model is progressively revised, sometimes dramatically, to remain consistent with the outcomes of new experiments suggested by the model itself. Thus, in the long haul, virtually all models prove to be incorrect, but even an incorrect model can suggest the way to a better one. For instance, the biological model called “Lamarckianism” — the inheritance of acquired characteristics — is incorrect in terms of present knowledge, but that does not mean that it resulted from bad science. In fact, it seemed to answer many questions posed at the time of its inception, e.g., why musicianship sometimes runs in families. It further suggested that an experiment of the sort, say, of cutting the tails off each of a line of mice would eventually result in a line of naturally short-tailed mice. The fact that things did not work out the way the Lamarckian model predicted led biologists to seek other models for inheritance and evolution. The fact that a model eventually proves to be inadequate should not lead us to be scornful about it; indeed, a mark of a good model is that it leads to its own rejection by suggesting experiments whose outcomes are so totally unexpected that a new model becomes necessary.

Applications, Further Discussion, And Additional Reading

- As an example of modeling, represent a human being as a light bulb. What size bulb (in watts, W) produces heat at the same rate as the human? Assume the bulb loses 90% of its input energy as heat and that the human consumes 2000 cal/day, all of which end up as heat. You should note that a dietitian’s calorie is 1 kcal on a physical chemist’s scale. (Answer: 106.6 W.)

- A survivorship curve is a plot of the number of surviving individuals vs. time, assuming zero birth rate. As a model, suppose that 1000 test tubes were purchased for a lab and that 10% of those remaining were broken each month. Thus, the survivors are 1000, 900, 810, etc. Plot a survivorship curve for these data. An elaboration of this model and some analogous biological data for a cohort of wild birds can be found on page 1039 of Life, 3rd ed., by Purves, W. K., Orians, G. H., and Heller, H. C., Sinauer Publishers, Sunderland, MA, 1992.

- The model of evolution called “Inheritance of Acquired Characteristics” was replaced by the Darwinian model, a basic conclusion of which is that properties favored by selection can be transmitted to offspring. Darwin proposed an utterly incorrect model, the “Provisional Theory of Pangenesis”, for the mode of this transmission, but that in no way detracts from the usefulness of the model of Darwinian evolution itself, the evidence for which is overwhelming and which is discussed in any introductory biology text. A discussion of Darwin’s ideas about pangenes, the basic concept of which actually dates back to Aristotle, can be found in History of Genetics by Stubbe, H., 2nd ed., 1965, translated by Waters, T. R. W., The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1972, pp. 172-175.

- There is a discussion of modeling in science in “Is science logical?”, by Pease, C. M. and Bull, J. J., BioScience, 42(4), 293-298,1992. (The authors answer “no” to their title question.)

Chapter 2

The Observation Process

Can Analysis Ever Be Truly Objective?

A scientist (or artist) is really an observer/interpreter, taking note of his or her surroundings and then trying to interpret those observations in some greater context. A scientist might see the mating behavior of a nematode in terms of chemical attractants, e.g., pheromones, found in all animals, including humans. On the other hand, an artist might paint a picture of a scene or write a poem about it, depicting his/her own reactions to the scene, and thus capture some universal feature of that scene. There are some interesting relationships between the processes of observation and interpretation. This chapter will examine some consequences of this interdependency.

We often convince ourselves that we are neutral observers and that our observations and interpretations are “objective”. Several things suggest that this conviction is overly optimistic. First, we are all victims of prejudice, having an emotional investment in the outcome of all our activities, scientific or not. In fact, experimenters usually try to build elaborate safeguards into their experiments to minimize the effects of personal bias. As an example, when a new vaccine is first tested, some patients must randomly be given the real vaccine and others must be given an inert placebo. As heartless as the latter act may seem, it is necessary to eliminate the possibility that the immunizing effect is due to the act of vaccine administration or to something in the carrier fluid for the vaccine. If the participating physicians can guess which solution is the real vaccine, they might administer it — rather than the placebo — to all their patients. Thus, the developers of vaccines go to great lengths to make the actual vaccine and the placebo look alike.

A second problem with our image of ourselves as neutral observers is in the notion that the actual act of watching, touching, or listening to something doesn’t influence the nature of that thing. We can take the simple process of observing a hen’s egg and show that detached objectivity — perception untainted by the observer — is not really possible, although its importance may be small (as explained below). Under the white light of an ordinary desk lamp, an egg appears white. However, under a red light the egg appears red, and so on. In the dark an egg has no color at all, but we might feel it and say that it is smooth and ovate. Evidently what we perceive the egg to be depends to some degree on the means we use to perceive it.

The egg example demonstrates a very fundamental principle: what something “is” is in large measure dependent on the observation process itself. This has the far-reaching consequence of making “reality” relative, i.e., relative to the observation process. The observer can never be totally detached from the observation process because he or she chooses the means of making the observation, and that in turn determines the nature of the object observed. Someone else might choose a different, but valid, method of observation and thus arrive at a different, but valid, conclusion. The notion of an “absolute reality” shared by everyone, thus becomes much less credible.

A third difficulty with our roles as supposedly objective observers was mentioned in Chapter 1; it is our need to form a “mental picture”, drawn from everyday life, of a phenomenon or thing which is not a part of our everyday life. In molecular biophysics this means that the things being interpreted are at the sub-microscopic scale, while our observations and interpretations are at the macroscopic scale. That disparity of scale has unexpected consequences. As an example, we could run an experiment to locate an electron by letting it hit a screen, such as the one on a television. The macroscopic model of such a collision is that of a projectile hitting a target and leaving a mark at the site of the collision: a pulse of light on the screen tells us where the electron hit and therefore where it was at the time of the collision. The phrase, “where it was” — past tense — is crucial because after hitting the screen the electron cannot subsequently be located. It is (perhaps) somewhere in the glass or the scintillator, but we will never know because it cannot be made to hit a second screen. Merely locating that electron a single time has forever cost us the ability to investigate that electron again.

The same problem doesn’t occur if we use the same macroscopic model for a collision involving an actual macroscopic object: let a car hit a large paper screen. The hole in the paper tells us where the car was, but doesn’t affect the car. We are confident that the car’s trajectory is unchanged by the observation; at this level, observation does not appreciably disturb the object observed.

The problem for us of course is that we aren’t interested in locating cars — we want to locate electrons, the observation of which requires comparatively large-energy-scale methods which seriously disturb electrons. This disturbance has no analog in our macroscopic world, a world which unfortunately forms the basis for all our models! We thus find ourselves in the peculiar position of constructing models out of a world that does not act like the one from which the biophysical systems originate.

We should note that the disparity-of-scale problem also occurs for extremely large objects. We might fancy that looking at a distant star through a telescope is just like looking through the telescope at a bird 50 ft away — a virtually instantaneous, straight line-of-sight view. Yet, light from stars may have started out billions of years ago and its path can be bent by passage near massive stars.

Applications, Further Discussion, And Additional Reading

- Alexander Kohn’s book, False Prophets, is a discussion of fraud in science. Kohn points out the role played by self-interest in causing scientists to make conscious or unconscious errors in taking, analyzing, and reporting data. Even Isaac Newton seems to have done it! (Kohn, A., False Prophets, Basil Blackwell, Cambridge, MA, rev. ed., 1988.)

- The thought that certain features of our physical world may not be accessible bothers many people. If the topic of “impossibility” interests you, you may want to read No Way: The Nature of the Impossible, Davis, P. J. and Park, D., Eds., W. H. Freeman, San Francisco, 1987. This book contains an article written by Park, entitled “When Nature Says No”.

Chapter 3

Electoomagnetic Radiatoon — A General Discussion

Electric Charges And Their Interactions

The words “positive” and “negative”, applied to electric charges, arise out of the need to combine aggregates of charge arithmetically and thus to obtain their net charge: ten electrons (negative charge) and nine protons (positive charge) have a net charge of −1. This nomenclature has the unfortunate side effect of suggesting that electrons electrically lack something that is present in protons. It will not do to suggest that the quality lacked is “positiveness” because we would then have to say that protons lack “negativeness”. In fact, there is no reason why the original assignment of charge sign could not have made electrons “positive”. The point of this discussion of semantics is to emphasize that the charges on electrons and protons have a perfect mirror symmetry, differing in sign only, their absolute magnitudes being identical. Differences in other aspects, such as mass, are irrelevant to their electrical properties.

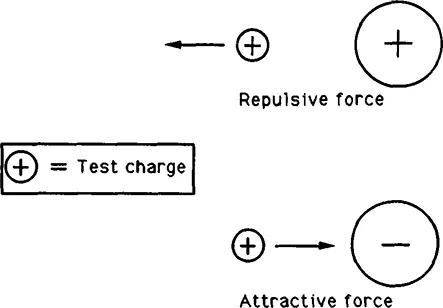

The fact that most material is electrically neutral masks the fact that it is composed of large quantities of positively and negatively charged particles. If there is an imbalance of those charges in an object, the object is said to be electrically charged. It is an empirical fact that two electrically charged objects exert a force on one another. The interaction of charged objects can be distilled to the statement, “unlike charges attract; like charges repel.”

Figure 3.1 Electrical force exerted by a massive charge on a small positive test charge.

We can study the interaction of two electrically charged objects in the following way: suppose that, as in Figure 3.1, there ex...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- The Author

- Contents

- Chapter 1: The Use Of Models in Science

- Chapter 2: The Observation Process

- Chapter 3: Electoomagnetic Radiatoon — A General Discussion

- Chapter 4: Electromagnetic Radiation — A Wave

- Chapter 5: Electromagnetic Radiation — A Particle

- Chapter 6: The Electron — A Particle

- Chapter 7: The Electron — A Wave

- Chapter 8: The Nucleus

- Chapter 9: The Atom — The Plum Pudding Model

- Chapter 10: The Atom — The Bohr Planetary Model

- Chapter 11: The Atom — The Quantum Mechanical Model

- Chapter 12: The Hydrogen Atom

- Chapter 13: Polyelectronic Atoms

- Chapter 14: The Covalent Bond

- Chapter 15: The Ionic Bond

- Chapter 16: The Hydrogen Bond

- Chapter 17: Van Der Waals’ Interaction

- Chapter 18: The Absorption Spectrophotometer

- Chapter 19: Solubility

- Chapter 20: Thermodynamics In Biology

- Chapter 21: The Flow Of Energy Through A Living System

- Chapter 22: Free Energy

- Chapter 23: The Coupled-Reactions Model

- Chapter 24: Actdvation Energy And Catalysas

- Chapter 25: Enzymes And The Determination Of Cell Chemistry

- Chapter 26: Material Transport

- Chapter 27: Metabolic Heat Generation And Loss

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Basic Biophysics for Biology by Edward K. Ph.D Yeargers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.