![]()

Chapter One

INTRODUCTION

Success has attended the global activities of the electronics industry since World War II. In consequence, it is regarded as a key sector by all and sundry. A US National Research Council report began by proclaiming that America’s ‘security and prosperity’ for the foreseeable future depended ‘increasingly on the strength of its electronics industry’ and maintained, in a valedictory address, that ‘the challenge to the United States is to formulate an industrial policy that will foster the ability of its electronics firms to compete vigorously in world markets’.1 The challenge, of course, has arisen because of the role arrogated by electronics as the locomotive of growth in modern economies, a development of such enormity that it portends massive structural changes not just in the American economy but worldwide. No less than a revamping of the global industrial system is at stake. As one observer wryly comments on the prospect of an Asian industrial powerhouse in the next century: ‘it will very likely be the result in no small measure of the momentum of electronics technology and the peculiar capacity of East Asian production systems to manage that technology most efficiently’.2 Spurred by the dynamism exhibited by the US and Japanese electronics industries, much of the rest of the world is scrambling to catch up, survive, or just enter into the alluring rewards that mere possession of electronics technology and its companion manufacturing supposedly brings. Many have embarked on crash programmes aimed at bolstering electronics R&D and industrial capability. European governments, scarcely without exception, have ploughed money into supporting their electronics industries, either singly, or in conjunction, under the EEC umbrella. The Soviet Union signals its belief in the importance of electronics by perpetrating industrial espionage in more technologica1ly-proficient nations. Reputedly, the Russians place great store on the acquisition--through commercial channels or otherwise--of Western process and product technologies in such areas as computers, superconductors, software, satellite communications, lasers and fibre optics; all prominent constituents of a sound electronics industry.3 Even East Asian newly-industrialising countries (NICs), hardly industrial laggards, insist on the fusion of government and corporate energies in formulating top-priority strategies expressly aimed at ‘staying the course’ in electronics. Taiwan, for example, is imperative that it ‘must nurture the technology and the industrial resources necessary for the production of more sophisticated products, such as computers, telecommunications equipment, and semiconductors, which are essential for strengthening the industrial foundation of our nation’.4

Paralleling the universally-held conviction of the decisive importance of electronics in national economic fortunes is to be found an equally compelling view that electronics is crucial to national defence and, consequently, must be encouraged to flourish as a key constituent of defence industry. The same sentient report on the US industry with which we commenced our discussion goes on to underscore the indispensable function of electronics in national defence. Asserting that military strength resides, in large measure, in electronic warfare (EW) capability, its authors further proclaim that ‘capability in command, control and countermeasure, surveillance, guidance, missile seekers, and communications is determined by the design, manufacture, and application of state of the art electronics technology’.5 Thus, the authors are of the opinion that attainment of expertise in any of the segments of EW is quite out of the question without the preliminary establishment of a galvanised electronics industry. In point of fact, recognition of the symbiotic nature of electronics technology and defence-industrial eminence is extremely longstanding, going back to the inception of electronics as a fully-fledged manufacturing industry distinct from the electrical-equipment sector which spawned it. The products issuing from the collaboration of electronics with the defence sector are both profuse and striking: radar, the computer, numerically-controlled machine tools (NCMTs), miniaturised components and graphics software all essentially owe their genesis to military needs or sponsorship. Nor is the defence interest less significant today even though the civilian side of the electronics industry has generally outpaced it in terms of the volume of output, the amount of employment generated and the level of public awareness. Far from subsiding, international rivalry in defence economics is serving, on the contrary, to impose a global division of labour on the electronics industry. In short, the advanced-industrial countries (AICs) have captured the high ground in EW capability--along with its attendant sophisticated R&D and production assets--leaving the NICs and less-developed countries (LDCs) to settle for very limited capabilities. Paradoxically, the latter’s impressive gains in the civilian electronics field are of little help in the recondite arena of defence electronics.6 Not surprisingly, NICs with military pretensions attach much weight to defence industry and brook no delay in adopting policies designed to promote defence-electronics capabilities as soon as returns from development enable them to do so. Concurrently, then, a large number of countries have concluded that promotion of electronics manufacturing is in the national interest either for critical developmental reasons or for pressing national defence ones: indeed, in quite a few cases, the two reasons in tandem are espoused. Given the salience of electronics, the aim of this book is to enlarge on the relationship between civilian and defence branches of the electronics industry and, within that rubric, to trace the global dispersion of the industry’s activities. Of crucial importance is the emergence of two ‘divisions’ of labour within the world electronics industry; that is to say, one pertaining to the civilian branch of it and the other, not necessarily conducive tc overlap, which is more appropriate for defence electronics. Before that grand object can be addressed, however, the question of terminology and industrial definition merits careful attention.

DEFINITIONS

At one level the definition of what constitutes the electronics industry is both straightforward and unequivocal: in sum, it is the assemblage of enterprises engaged in the manufacture of electronics devices. Yet at another, and deeper level, the definition is far more involved and convoluted. Electronics devices, when all is said and done, are simply implements that make use of electrons moving in a vacuum, gas or semiconductor.7 But maintaining that the electronics industry is the manufacture of electronics devices is something analogous to claiming that the manufacture of aerofoils suffices to explain the function of the aerospace industry. The exiguous nature of such definitions obviously calls for clarification and, here, the electronics industry is invested with several difficulties. For one, electronics is usually bracketed with electrical engineering to form a monolithic entity for official statistical purposes. Distinguishing the magnitude of one industry from that of the other in formal records is no mean feat. However, even when detached from its electrical parent in an official category of its own, there is some vagary as to the critical distinguishing feature of electronics. All are in agreement that electronics can be branded by its preoccupation with manufacturing electronic circuitry but there the consensus breaks down. The distinction, then, seems to lie in the specific technology that arises out of the need of circuitry to accommodate smaller currents than those required by electrical-engineering plants. Units of the electronics industry not only possess this technology, but are capable of producing ‘active’ components, or those equipped to modify the electricity flow.8 These discerning characteristics still leave a myriad of seemingly-diverse activities under the electronics industry banner. One cornerstone is provided by microelectronics, or that branch of the industry devoted to the manufacture of devices constituted from extremely small electronics parts. Scant reflection, though, is enough to expose the pitfall of such a definition; namely, it neither defines the degree of miniaturisation necessary to embrace microelectronics nor does it exclude any of the welter of electronics products, commercial or military, from its domain. As one convention would have it, the microelectronics industry is merely the business of designing and producing monolithic integrated circuits blessed by another, more pert name. For the pedants, membership of this collective group rests on a number of fairly arcane technical features, not least of which are the triple requirements that the circuitry be manufactured in a single process cycle, that it is of integrated rather than discrete form, and that it resides on a semiconductor substance such as silicon (Si), germanium (Ge) or gallium arsenide (GaAs).9 This definition appears to be overly restrictive, however, since the term ‘microelectronics manufacturing’ is often used to refer to producers of such devices. Similar qualifications mar the other popular divisions of the industry. Defence electronics, for example, obviously encompasses all electronics devices destined for military end-users, but functionally such a broad-sweeping definition could embrace the entire range of devices produced by the electronics industry, especially if the components inserted into the devices are taken into account. In view of these evident shortcomings in demarcating the functional branches of electronics, we shall settle for an outline of their essential ingredients and, henceforth, repudiate any tendency to assume that the various categories of electronics manufacturing denote exclusive functional classes.

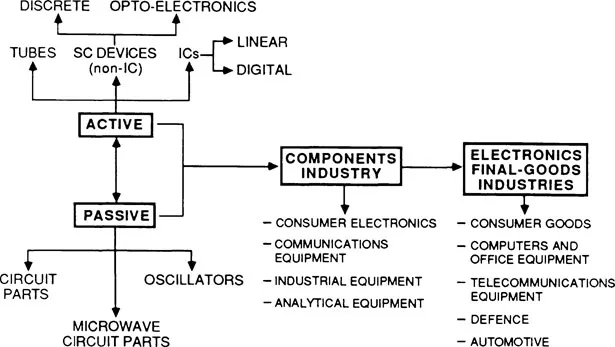

Figure 1.1 offers a guide to the family of electronics activities. Therein, a fundamental distinction is made between the units of the electronics-components industry and those which compose electronics final-goods industries. The first group encompasses that most commonplace variant, consumer electronics, as a principal constituent; and is joined by communications equipment, industrial equipment and analytical equipment. The second group also embraces consumer electronics, although now transformed into final-demand form. Accompanying it in the congress of final-goods industries are computers and office equipment, telecommunications equipment (the final-demand development of communications equipment), defence industry and the automotive industry. The membership of both groups is partly arbitrary. For example, test and measurement equipment may be deemed sufficiently different from analytical equipment to warrant separate classification within the components group whereas, for its part, the final-goods group could delete the automotive industry in favour of the aerospace industry (which is largely subsumed in the defence category in any case). Quibbling aside, the broad dichotomy is important for underlining the fact that the electronics industry contains within its own bounds large input-producing (component supplying) activities as well as significant input-absorbing (component using) activities. Conventionally, and by way of contrast, most industries conform to a more limited range of interdependent activities: shipbuilding, for instance, fabricates and assembles inputs (steel, diesel engines, navigation equipment and so on) produced by very different supplier industries from itself while the linked refining and processing aspects of the iron and steel industry rely on inputs from outside the manufacturing sector altogether (i.e. the products of ore, coal, flux materials, oil and other extractive activities). The scale of the electronics industry is far greater, and the enormity of its dimensions has an evident disabling side; namely, its very size precludes a ready grasp of the magnitude and direction of intra-industry material and financial flows linking together the various constituent parts. Yet, the sheer complexity and comprehensiveness of electronics activities throughout the world’s industrial fabric commands attention and, perforce, requires that attempts be made to explore their intra-industry ramifications.

Figure 1.1 : The electronics schema

To begin with the component-industry group, and regardless of whether the particular industry is consumer electronics, communications, industrial or analytical-equipment manufacturing, a definite benchmark presaging all other differences is apparent, and that is the partition of activities into production of active or passive components. As aforementioned, the former is central to the definition of electronics and in its manufacturing mode entails the production of all components except for those associated with properties of pure resistance, capacitance and inductance. These exceptions, in combination, comprise passive components. Undoubtedly, active components are the more pronounced of the two, underscoring three key industries; to wit, the production of integrated circuits (ICs), the manufacturing of other semiconductor (SC) devices, and the making of electron tubes (valves). Conventionally, and despite the perceptible distinctions, the first two activities are collapsed into one category denoted by the ‘SC industry’ banner. Semantics apart, components can take the form of standard, semicustom and custom devices, depending on the intended market. Standard components are geared to volume production and multiple uses; they are cost-efficiently produced, enjoy low prices and high reliability but suffer from sub-optimal space usage.10 Semicustom devices attempt to share as far as possible the generic and economic characteristics of standard devices while being produced with specific customers in mind. Custom devices, meanwhile, come into their own in niche markets and, as their name implies, are tailored to meet very explicit customer requirements. As such, they are more costly to produce, both in the fiscal and time sense, than any other kind of component. Sensible of the space-usage advantages to be gained from the incorporation of specific functional properties, the components makers must balance the higher prices of such devices against the smaller production runs, more demanding tooling, an...