- 326 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Originally published in 1989 Defence Industries presents a worldwide survey of defence industries. It argues that modern weapon systems and electronic warfare have led to the transition of the military-industrial enterprise into a multifaceted entity where electronics production is the key. It analyses the extent of defence industries, showing that large portions of the aerospace, shipbuilding, motor vehicle and electronics industries are devoted to defence and discusses where the defence industries are located. It examines the differences in government policies, contrasting the superpowers, with newly industrialised countries.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Routledge Revivals: Defence Industries (1988) by Daniel Todd in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Betriebswirtschaft & Business allgemein. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Arms Spending and Defence Industries

Before embarking at the beginning, that is, with a discussion of general patterns of international defence procurement, a few qualifications are in order concerning the value of military expenditure data. First and foremost is the lack of standardisation of national data and the problem of comparability thereby posed: a problem, incidentally, which has heretofore remained unresolved despite the best efforts of ACDA and SIPRI. Moreover, the content of 'defence expenditure' and its valuation often appear ambiguous. In terms of the former, the magnitude of the defence effort may vary by alarming proportions depending on the definition adopted.1 As for the latter, serious problems in valuation can be occasioned by inflation and exchange rate effects, not to speak of distortions caused by the difficulty of pricing non-marketable commodities. As if this was not enough, one dollar of military expenditure in one country does not necessarily deliver the same amount of capability as a dollar spent in another country owing to widely differing technological, production and manpower endowments. All told, then, any utilisation of aggregate defence expenditure data, whether from international agencies or directly from national accounts, must be treated with the utmost caution.

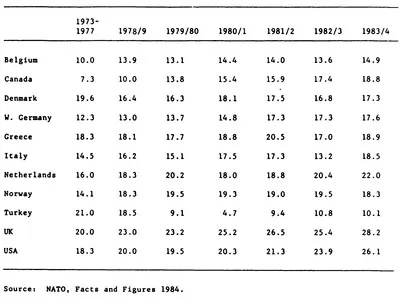

Caution notwithstanding, some aggregate trends are immensely telling. Most salutary is the sustained increase in world military spending despite sluggish and uneven growth in the global economy. In fact, military expenditure now approaches $1,000,000,000,000 and, what is more, has been subject to accelerating growth. Thus, while the average annual real growth of world military expenditure between 1975 and 1980 registered 1.5 per cent, the figure had leapt to 3.2 per cent in the succeeding quinquennium—and did so despite a rate of increase in world GDP of only 2.4 per cent.2 These aggregate figures, however, obscure considerable geographical variations. For the developing countries as a whole, GDP grew at an annual rate of 1.8 per cent whereas military expenditure expanded at 3.1 per cent. For countries with per capita incomes of less than $440, real military spending has grown at a rate of four per cent per annum since 1976. Yet most weight must be attached to the activities of NATO and the Warsaw Pact which together account for 73.5 per cent of global outlays in roughly equal proportion. The USA and USSR are dominant within each bloc, with the former, for example, arrogating more than 60 per cent of total NATO outlays. It and its alliance partners have been committed since 1978 to the Long Term Defence Programme, an augmentation strategy requiring each member to accede to annual real defence expenditure increases of approximately three per cent. In the event, this target was not consistently adhered to, although defence budgets increased everywhere. A principal outcome was the increase in the share of defence outlays earmarked for equipment (Table 1.1).

In general, global patterns of defence equipment purchases have been on the rise in conjunction with changes in the form of defence production, the emergence of new defence industries—in both geographical and technological senses of the term—and the restructuring of defence procurement policy. The processes underpinning these changes are pervasive, with the most critical being the incessant drive on the part of the advanced-industrial countries (AICs) to generate and maintain technological advantages and its corresponding response, that is to say, the desire of the newly-industrialising countries (NICs) to acquire as much defence production capability as possible. Essentially, the post-World War 2 division of labour in defence production, marked by the overwhelming dominance of the USA and USSR, is giving way to a more stratified division among a greater number of producers.3 Position in the global defence industry hierarchy is a function of the size of the national economy, that enabling agent providing the resource base necessary to initiate defence production and secure production economies, as well as the level of development of the nation's technology. The two are to a certain degree interdependent and both are necessary if across-the-board capabilities are to be established and retained. Thus, while a country like China possesses size sufficient to indigenously provide comprehensive capabilities, technological constraints necessitate the import of advanced systems to upgrade weapon performance. By way of contrast, countries such as the UK and France occupy an intermediate position, producing much but not all of the technological spectrum of weapons systems. The UK's attempt, for example, to develop domestically an AEW aircraft is an apt illustration of technical and financial constraints collectively impinging on the scope of the defence-industrial base. After nearly £1 billion of Nimrod programme development expenditure, continuing problems with the mission system avionics compelled the MoD to forsake the home product in favour of the E-3A AWACS supplied by US contractors (a course subsequently adopted by France).

Table 1.1: Equipment Share of Total Defence Outlays

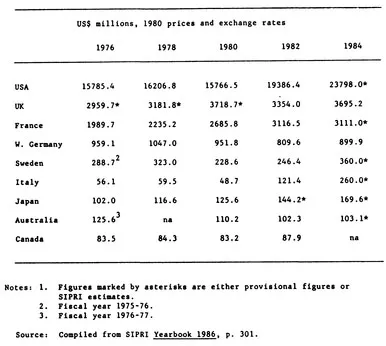

As with other products, international competitiveness in defence production rests, in part, on principles of comparative advantage and functional specialisation. In turn, these economic truisms rely on a crucial 'software' input; namely, the capacity to design and develop effective weapons systems. Of vital importance in this regard is the willingness to devote resources to military R & D. Table 1.2 offers a rough indication of the design capacity of defence industries in the AICs simply on the premise that more expenditures channelled into R&D should be forthcoming with deeper weapons system expertise. The USA and USSR together accounted for some 80 per cent of the $80 billion (current prices) devoted to global military R & D in 1985. The addition of the UK, France, China and West Germany places a select group of countries in the position of accounting for fully 90 per cent of world military R & D expenditures. With technology given pride of place in the defence industries of AICs, the importance of R & D is obvious. In both the USA and UK, for instance, the sustained increases in defence spending have especially favoured R&D allocations. For example, the Reagan build-up witnessed defence HID outlays escalate from a 1980 level of $7.7 billion (in 1972 dollars) to $11.4 billion in 1984, a real increase of 48 per cent.4 Among the more important technological ventures undertaken during this period are the Very High Speed Integrated Circuit programme and the Strategic Defence Initiative (SDI). For its part, R&D expenditures in the UK climbed from £1.6 billion in 1980-1 to £2.1 billion in 1984-5, an almost 30 per cent increase.5

The implication of the concentration of defence R&D outlays is that it clearly places the leading edge of defence technology in the hands of only a few producers. Control over technological resources is a key factor in determining which countries are likely to be in a position to occupy the early stages of the defence product cycle. This technological leadership accorded to the AICs has far reaching consequences in setting the technological agenda for future arms production and thereby perpetuating the existing hierarchy of defence industries. The most important area of emerging technology is defence electronics which, in the words of the US Defense Science Board, 'is the foundation upon which much of our defense strategy and capabilities are built', and is the basis of enhancing performance and survivability of weapons systems.6 Consistent with such thinking is the increasing share of defence spending devoted to the electronics sector. In the USA, the electronics share of the R&D budget is scheduled to grow from 49 per cent in 1987 to 54 per cent in 1996 while its share of the procurement budget is to rise from 35 to 40 per cent and amount to a staggering $51 billion. The increasing importance of electronics is attributable to

Table 1.2: Military R&D Expenditure

expanded use of lasers, infra-red devices, fibre optics and electro-optics for surveillance, target location and designation, communications and guidance as well as the wider use of millimetre wave hardware for secure communications and weapons guidance.7 Particularly critical are guidance and surveillance systems and, significantly, production capability in these areas is almost exclusively the preserve of a few AIC defence industries.8 The concentration of defence R & D is additionally meaningful in that it points to the dependence of smaller producers on the transfer of technology. For these producers, entry into defence markets is generally predicated on their ability to select niches where price competition is relatively more important than the preoccupation of the major producers; namely, performance criteria. By the same token, market access for those smaller defence industries is contingent on their obtaining quality sub-systems from the AICs for the products geared to market niches. For example, Brazil's successes in the global arms trade would have been impossible without access to fore...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Original Title

- Original Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- 1. ARMS SPENDING AND DEFENCE INDUSTRIES

- 2. EMPIRICAL DIMENSIONS OF THE ARMS ECONOMY

- 3. THE CONCEPTION OF THE MIE

- 4. THE EVOLUTION OF THE TRADITIONAL MIE

- 5. THE MODERN MIE

- 6. THE EMERGENT MIE

- 7. CONCLUSIONS

- Glossary

- References

- Index