![]()

Can verbal working memory training improve reading?

Erin Banales, Saskia Kohnen and Genevieve McArthur

Department of Cognitive Science, ARC Centre of Excellence in Cognition and its Disorders, Macquarie University, North Ryde, Sydney, NSW, Australia

The aim of the current study was to determine whether poor verbal working memory is associated with poor word reading accuracy because the former causes the latter, or the latter causes the former. To this end, we tested whether (a) verbal working memory training improves poor verbal working memory or poor word reading accuracy, and whether (b) reading training improves poor reading accuracy or verbal working memory in a case series of four children with poor word reading accuracy and verbal working memory. Each child completed 8 weeks of verbal working memory training and 8 weeks of reading training. Verbal working memory training improved verbal working memory in two of the four children, but did not improve their reading accuracy. Similarly, reading training improved word reading accuracy in all children, but did not improve their verbal working memory. These results suggest that the causal links between verbal working memory and reading accuracy may not be as direct as has been assumed.

Reading is a skill that is often taken for granted, and thus the cause of poor word reading is not always clear. Two processing deficits that have been posited as potential causes of poor word reading are poor short-term memory and poor working memory (e.g. Alloway & Alloway, 2010; Jorm, 1983). Short-term memory refers to the ability to store information for a short period of time (around 2 seconds), which can be extended via rehearsal (Baddeley, 2012). For example, it is the ability to remember a friend’s request for “a large, extra hot, double-shot, soy latte with three sugars” until you reach the counter to order. Working memory refers to the ability to both store and manipulate information, or to continue to store information in spite of interference from other stimuli (Baddeley, 2012). Thus, working memory would allow you to hold the same coffee order in mind while someone in the queue asks you for directions to the nearest train station.

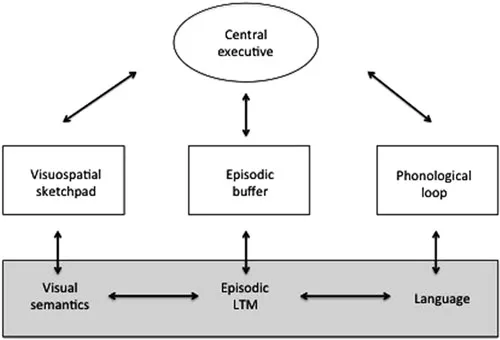

Baddeley’s working memory model (see Figure 1) has been highly influential in studying short-term and working memory (Baddeley, 2000; Baddeley & Hitch, 1974). The model consists of four components: the phonological loop, visuospatial sketchpad, episodic buffer, and central executive. The phonological loop can be thought of as short-term memory for verbal or auditory information, while the visuospatial sketchpad can be thought of as short-term memory for visual or spatial stimuli. The central executive is the component that provides the capacity to manipulate information, or to continue to store information in spite of interference from other stimuli. Finally, the episodic buffer is thought to provide a buffer store for the subcomponents, as well as a link between the central executive and long-term memory.

Figure 1. Baddeley’s working memory model (Baddeley, 2000). © Elsevier. Reproduced from Baddeley (2000) by permission of Elsevier. Permission to reuse must be obtained from the rightsholder.

The central executive combined with the phonological loop represents verbal working memory, while the central executive combined with the visuospatial sketchpad represents visuospatial working memory. Both types of working memory have the capacity to maintain and store a limited amount of information (Baddeley, 2003). Working memory has been described as the mind’s “workspace” (Morrison & Chein, 2011) or “post-it note” (Alloway & Copello, 2013) and has been linked to other cognitive processes that may depend upon such a “workspace”, such as reading (Jorm, 1983), arithmetic (De Smedt et al., 2009), and fluid intelligence (Engle, Tuholski, Laughlin, & Conway, 1999). Verbal working memory is thought to be particularly important for children in the classroom, as it is used for activities such as remembering lengthy instructions or place keeping in text (Gathercole & Alloway, 2007).

While both verbal and visuospatial working and short-term memory deficits have been found in poor readers, verbal memory deficits appear to be more common (see Swanson, Zheng, & Jerman, 2009, for review). Verbal short-term memory is often tested by asking a participant to repeat a list of numbers (known as “forward digit span” or simply “digit span”). Alternatively, verbal working memory is often tested by asking a participant to repeat a list of numbers in backward order (i.e. storing and manipulating information; known as “backward digit span”). The other component of working memory—the ability to store information in the face of interference—is often tested by complex span tasks. An example of this is the Listening Recall task, in which participants are required to validate a series of statements (i.e. declare whether the statements are true or false) before recalling every final word of every statement. Verbal short-term memory is often seen as a subset of verbal working memory; however, it has been demonstrated that these skills are related, but separable, constructs that develop independently of each other (Swanson et al., 2009).

Initially, verbal short-term memory was linked to reading accuracy (e.g. Jorm, 1983), while verbal working memory was linked primarily to reading comprehension (e.g. Swanson & Berninger, 1995). However, more recent research has demonstrated that verbal working memory is a better predictor of reading accuracy than verbal short-term memory (Gathercole, Alloway, Willis, & Adams, 2006; Gathercole, Tiffany, Briscoe, & Thorn, 2005). There is still much to be understood about this relationship, and thus the focus of this study is the relationship between poor verbal working memory and poor word reading accuracy.

A number of studies have found an association between poor verbal working memory and poor word reading accuracy (e.g. Roodenrys & Stokes, 2001; Siegel, 1994; Siegel & Ryan, 1989; Wang & Gathercole, 2013). This evidence has led to theories suggesting that poor verbal working memory causes poor word reading accuracy (e.g. Brady, 1991; Gathercole & Baddeley, 1993; Howes, Bigler, Lawson, & Burlingame, 1999; Schuchardt, Bockmann, Bornemann, & Maehler, 2013). Of these theories, it is those that might be loosely categorized as “phonological decoding” theories that currently provide the most clearly specified chain of causal events leading from poor verbal working memory to poor word reading accuracy. It has been suggested that:

During reading, written letters have to be decoded into corresponding sounds. These sounds need to be stored temporarily in the phonological working memory, which allows them to be merged into a sound sequence.… So, a necessary precondition of correct word identification is the child’s ability to maintain sounds and sound sequences in working memory (Preßler, Könen, Hasselhorn, & Krajewksi, 2014, p. 386).

Support for phonological decoding theories comes from longitudinal studies that have found that verbal working memory in young children is correlated with their later word reading accuracy (Pham & Hasson, 2014; Preßler et al., 2014). Unfortunately, this support is limited by the fact that these studies tested participants who had either already begun to read (Pham & Hasson, 2014) or whose reading experience was unknown (Preßler et al., 2014). Since there is evidence that learning to read improves a person’s verbal working memory (Ardila, Ostrosky-Solís, & Mendoza, 2000), it is possible that these studies found that early verbal working memory is associated with later word reading accuracy simply because early reading ability defined verbal working memory in the first place (Brunswick, Martin, & Rippon, 2012).

A stronger test of the causal effect of poor verbal working memory on poor reading accuracy could be provided by intervention studies (Nickels, Kohnen, & Biedermann, 2010). Such studies allow for the direct manipulation of variable A (e.g. poor verbal working memory) to determine whether it has a causal effect (in this case, a negative effect) on variable B (e.g. reading). Unfortunately, there are very few studies that have examined the effect of working memory training on word reading (see Melby-Lervåg & Hulme, 2013, for review), and to the best of our knowledge, no study has yet tested the effect of training poor verbal working memory on poor word reading accuracy. More specifically, no study has recruited a group of children with demonstrated impairments in both verbal working memory and word reading and measured the effect of training their poor verbal working memory on their poor reading. Instead, studies that have examined reading improvement (i.e. comprehension, fluency, or accuracy) following working memory training have (a) trained visuospatial working memory alone in typically developing children (Loosli, Buschkuehl, Perrig, & Jaeggi, 2012); or (b) trained a combination of auditory (i.e. nonverbal) and visuospatial working memory in adults with dyslexia (Horowitz-Kraus & Breznitz, 2009; Shiran & Breznitz, 2011); or (c) have trained verbal working memory in conjunction with visuospatial working memory in children with dyslexia (Luo, Wang, Wu, Zhu, & Zhang, 2013), children with low working memory (Dunning, Holmes, & Gathercole, 2013; Holmes, Gathercole, & Dunning, 2009), children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and special education needs (Dahlin, 2011), adolescents with intellectual disabilities (Van der Molen, Van Luit, Van der Molen, Klugkist, & Jongmans, 2010), or adults with typical reading (Chein & Morrison, 2010). To the best of our knowledge, the only study to train pure verbal working memory in children with poor word reading did so with the intent to examine the effect of the training on verbal working memory and thus did not report the effect on reading (Brady & Richman, 1994). The absence of any studies that have trained verbal working memory in people with known deficits in both verbal working memory and word reading means that we currently do not know whether training poor verbal working memory has an effect on poor word reading accuracy.

The same is true for the “reverse” causal effect of poor word reading accuracy on poor verbal working memory. It has been suggested,

… reading—even slow reading—might stimulate the development of phonological abilities and boost the performance of other phonology oriented tasks, such as simple and complex span tasks. Working memory capacity might, therefore, improve to age-appropriate levels under the influence of the act of reading itself (van der Sluis, van der Leij, & de Jong, 2005, p. 219).

Evidence for a causal effect of poor reading in general on verbal working memory comes from a variety of sources. It has been found that illiterate adults demonstrate a deficit in verbal working memory compared to literate controls (Silva, Faísca, Ingvar, Petersson, & Reis, 2012). Further, training studies have discovered that reading instruction leads to gains in verbal working memory in illiterate adults (Ardila et al., 2000), poor comprehenders (Johnson-Glenberg, 2000), and Italian children with fluent yet inaccurate reading, or with dysfluent yet accurate reading (Lorusso, Facoetti, & Bakker, 2011). The latter is particularly relevant to the current study since it suggests that training poor reading has a causal effect on verbal working memory. However, this study does not report whether these children had poor verbal working memory to start with, and they reported the effect of reading training on a “global memory score” (i.e. the average of scores for short-term memory, working memory, long-term memory, and verbal learning). Thus, it is not clear whether training poor word reading accuracy has a causal effect on poor verbal working memory or not.

In sum, a number of correlational studies have produced evidence for an association between poor verbal working memory and poor word reading accuracy. These studies have prompted theories positing a causal effect of poor verbal working memory on poor word reading accuracy. However, this association may exist because limited reading experience impairs the development of verbal working memory, rather than limited verbal memory impairing the development of reading. To our knowledge, no study has yet tested the effect of training poor verbal working memory on poor word reading accuracy in English-speaking poor readers with poor verbal working memory, and no study has tested the effect of training poor word reading accuracy on poor verbal working memory. Given our incomplete theoretical understanding of why poor reading is associated with verbal memory deficits, the aim of this paper is to utilize verbal working memory intervention to investigate the causal link between verbal working memory and word reading accuracy. We aimed to do this by determining whether (a) training poor verbal working memo...