![]()

1 | Scope and History of Microbioiogy |

1.1 MICROBES AND MICROBIOLOGY

1.1.1 GENERAL CONCEPTS OF MICROBIOLOGY

The science of microbiology is study of microorganisms and their activities. You may ask, exactly what is a microorganism and how do microorganisms differ from other organisms?

The word microorganism originates from the Greek word micro, meaning small. Microorganisms are very small life forms—so small that individual microorganisms usually can only be seen with magnification. Microbiology is also concerned with the forms, structure, reproduction, physiology, metabolism, and identification of microbes. To study microorganisms, we must be familiar with their distribution in nature, their relationship to each other and other living organisms, their beneficial and detrimental effects on man, and the physical and chemical changes they make in their environment.

The major groups of microorganisms are bacteria, algae, fungi, viruses, and protozoa. All are widely distributed in nature.

1.1.2 SIZE OF MICROORGANISMS

Microbes range in size from small viruses 20 nm in diameter to large protozoans 5 mm or more in diameter (see Appendix B for a review of the metric system).

Resolution or resolving power refers to the ability of lenses to reveal fine details or two points distinctly separated. The resolution of the naked eye is 0.1 mm. This means that the naked eye can distinguish between two subjects that are not smaller than 0.1 mm. Most microorganisms are smaller than 0.1 mm, so we need a microscope to increase the resolving power to make the microorganisms visible.

1.1.3 UNICELLULAR AND NONCELLULAR ORGANISMS

For the most part, microbiology deals with unicellular microscopic organisms. In unicellular organisms, all the life processes are performed in a single cell. Regardless of the complexity of an organism, the cell is the true, complete unit of life. According to cell theory, the smallest unit of life is one cell, nothing smaller or simpler is alive.

All living cells are basically similar. They are composed of protoplasm, a colloidal organic complex, consisting largely of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. All are bordered by lining cell membrane or cell membrane and cell wall, and all contain a nucleus or an equivalent nuclear substance with genetic material.

In the study of microbiology, we also encounter organisms that may represent the borderline of life. These organisms are viruses and viruses do not fit the basic characteristics of any living system.

1.1.4 BASIC CHARACTERISTICS OF LIVING SYSTEMS

Any living system, unicellular or multicellular, must have the following basic characteristics:

1. The ability to reproduce new cells either for growth, repair or maintenance, or production of a new individual.

2. The ability to ingest food and metabolize it for energy and growth.

3. The ability to excrete waste products.

4. The ability to respond to changes in the environment, called irritability.

5. The ability to mutate.

1.1.5 INVESTIGATION OF MICROORGANISMS

Microorganisms have provided specific systems for the investigation of the physiologic, genetic, and biochemical reactions that are basis of life. They can be conveniently grown in test tubes or in petri dishes. They grow rapidly and reproduce at an unusually high rate.

Some bacteria go through about 100 generations in one 24 h period. In microbiology, we can study organisms in great detail and observe their life processes while they are actively metabolizing, growing, reproducing, aging, and dying. By modifying their environment, we can alter metabolic activities, regulate growth, or destroy the organism. Microbiologists have been remarkably successful in explaining the useful microorganisms and in combating the harmful ones.

1.2 BRIEF HISTORY OF MICROBIOLOGY

1.2.1 THE MICROSCOPE AND MICROBES

Considering the small size of the microorganism, it is no wonder that the existence of microorganisms was not recognized until a few centuries ago. The science of microbiology was born when men learned to grind lenses from pieces of glass and to combine the lenses to produce magnifications large enough to see microbes.

In about 1665, an English scientist named Robert Hook prepared a compound microscope and used it to observe thin slices of cork which was composed of walls of dead plant cells. Hook called the small boxes cells, because they reminded him of monks’ cells. This observation and the discovery of building blocks in plants of a cell structure marked the beginning of cell theory.

It was the Dutchman Anton van Leeuwenhoek, an amateur scientist and cloth merchant, who first made and used lenses to observe our environment and living organisms; see Figure 1.1. The lenses Leeuwenhoek made were of excellent quality; some gave magnification up to 200 to 300 times and were remarkably free from distortion. Making these lenses and looking through them were the passions of Leeuwenhoek’s life. Starting in the 1670s, he wrote numerous letters to the Royal Society of London describing the animalcules he saw through his simple, single lens microscope.

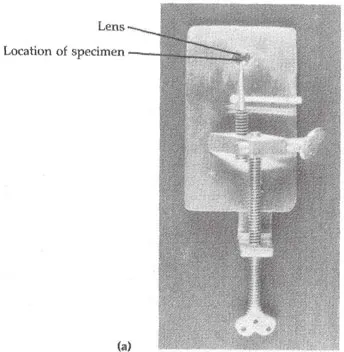

Leeuwenhoek made detailed drawings of the microbes he saw under the microscope in rain water, peppercorn infusion, and in material taken from teeth scrapings. They were identified as representations of bacteria in spherical, rod, and spiral forms, protozoa, algae, yeast, and fungi. He pursued his studies until his death in 1723 at the age of 91. His picture and his simple microscope are seen in Figures 1.1 and 1.2.

Leeuwenhoek refused to sell his microscopes to others and so he failed to foster the development of microbiology as much as he might have.

1.2.2 SPONTANEOUS GENERATION VS. BIOGENESIS THEORY

After Leeuwenhoek discovered the invisible world of microorganisms, the scientific community became interested in the origins of these tiny living things. Until the second half of the nineteenth century, it was generally believed that some forms of life could arise spontaneously from nonliving matter. This process was known as spontaneous generation.

FIGURE 1.1 Anton van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723) was the first to describe microbes (bacteria and protozoa) under a microscope. He is known as the father of microbiology and he was the first to examine our environment.

FIGURE 1.2 a. Leeuwenhoek’s simple microscope.

People thought that toads, snakes, and mice could be born of moist soil, that flies emerged from manure, and maggots could arise from decaying corpses. Common people embraced the idea, for even they could see slime breeding toads, and meat generating worm-like maggots.

In 1749, British clergyman John Needham put forth the notion that microorganisms arise by spontaneous generation in flasks of molten gravy. Needham experimented with meat exposed to hot ashes, observed the appearance of organisms not present at the start of the experiment, and concluded that the bacteria originated from the meat.

Francesco Redi disputed the theory of spontaneous generation. Redi performed a series of tests in which he covered jars of meat with fine lace preventing the entry of flies and showed that the meat would not produce maggots when protected from flies. Years and years passed with arguments and experiments against the spontaneous generation theory without this proof being accepted. Redi’s experiment is shown in Figure 1.3.

In 1858, the German scientist Rudolf Virchow challenged the spontaneous generation theory with the concept of biogenesis. He said, “Omnis cellula ex cellulae,” that living cells originated from another preexisting living cell.

Finally, in 1861, Louis Pasteur (1822–1895) performed experiments that ended the argument for all time, see Figure 1.4. “There is no condition known today in which you can affirm that microscopic beings come into the world without germs, without parents like themselves. They who alleged it have been the sport of illusions of ill-made experiments, vitiated by errors which they have not known how to avoid.” Pasteur demonstrated that microorganisms are indeed in the air and can contaminate seemingly sterile solutions, but air itself does not create microbes. He began by filling several short-necked flasks with beef broth and then boiling their contents. Some were then left open and allowed to cool. In a few days, these flasks were found to be contaminated with microbes. The other flasks, sealed after boiling, remained free of microorganisms. From these results, Pasteur reasoned that microbes in the air were the agents responsible for contaminating nonliving matter.

Pasteur next placed broth in open-ended long-necked flasks and bent the necks into S-shaped curves. The contents of these flasks were then boiled and cooled. Even after months, the broth in the flasks did not decay and showed no signs of life. Pasteur’s unique design allowed air to pass into the flask, but the curved neck trapped any airborne microorganisms that might contaminate the broth. Pasteur showed that microorganisms can be present in nonliving ...