- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The British Empire at its Zenith

About this book

This title, originally published in 1988, examines the network of states and the political and economic systems which bound the British Empire together. This book examines each country and how the empire made its mark in the shape of urban form, public buildings and rural land patterns. An overall assessment of the Imperial heritage is attempted as a pointer to the unity which existed between the many diverse lands for a brief period in their history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The British Empire at its Zenith by A. J. Christopher in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Overview

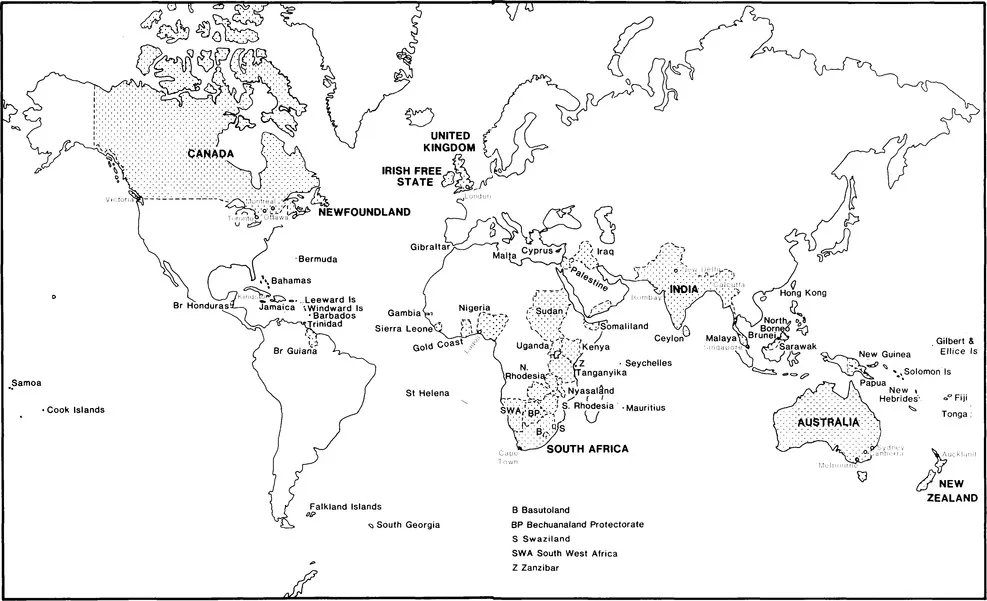

The British Empire, which attained its maximum territorial extent after the First World War, was one of the largest political entities ever constituted in world history (Figure 1.1). The Empire had been extended by a variety of means, including direct conquest from indigenous powers as in the case of parts of India or Hong Kong, through the legal process of annexation of apparently uninhabited regions as in Australia or Barbados, and acquisition by the conclusion of protection treaties with indigenous rulers in New Zealand and Fiji. Lands had been traded between the European powers in the course of expansion and even acquired as dowries, most significantly Catherine of Braganza’s inheritance of Bombay; or by purchase in the case of the Dutch and Danish West African possessions; or seized in the course of European wars in the case of Canada and Jamaica. The history of Empire had not been a story of steady territorial expansion. The revolt and independence of the 13 North American colonies was the greatest and most disastrous loss prior to 1947, but territories had been abandoned as uneconomic and indefensible (Tangier, 1661–81), or granted independence but subject to indirect military control (Egypt, 1922). Possessions had also been exchanged with other powers for diplomatic gain (Heligoland to Germany, 1890) or ceded to friendly countries, when considered of limited value or political liability (Ionian Islands to Greece, 1864; Bay Islands to Honduras, 1860).

The picture which emerges in one of flux and change in territorial extent as well as change in terms of internal structure. In the 1930s Iraq became an independent kingdom while the Dominions gained formal recognition of their constitutional independence under the Statute of Westminster. The process of fragmentation thus took a major step forward, although it was only in the 1940s that the dissolution became more apparent after the strains of the Pyrrhic victory in the Second World War. The granting of independence to India, the key to the post-1784 British Empire, hastened decolonisation elsewhere. Thus to embrace the British Imperial imprint and the organisation behind it, no date later than the early 1930s can be entertained as the ensuing era of economic depression, war and independence blurs the semblance of a picture of an Imperial entity.

Figure 1.1: The British Empire, 1931

Political Structures

Political structures within the British Empire in the 1930s exhibited a remarkable diversity and lack of an overall philosophy of Imperial administration. Hyam (1976: 15) considered that ‘there was no such thing as Greater Britain, still less a British empire, India perhaps apart. There was only a ragbag of territorial bits and pieces.’ The concept of a single unit Empire or Imperial federation had died and the unique character of each of the component parts of the Empire was steadily enhanced in the twentieth century. If the special status of Northern Ireland and the Irish Free State are ignored, constitutional development in 1930 ranged from the virtually independent dominions of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Newfoundland, which maintained only tenuous links with Great Britain through a common sovereign, to directly administered colonies ruled by appointed governers and nominated councils subject to control from the Colonial Office in London.

In addition there were three ambiguous political statuses which further diversified the structure. In the first case the British government had entered into protection agreements with indigenous rulers who retained a measure of control over their own affairs. These ranged from the nebulous suzerainty agreement linking the Nizam of Hyderabad to the British Indian Empire, on the one hand, to the numerous small groups in Africa, on the other, whose chiefs retained no more than ceremonial functions under colonial control. Even the White Rajah, Charles Vyner Brooke, of Sarawak and the Chartered Company of British North Borneo were linked tenuously to the overall structure through protectorate agreements. The second anomaly was the various mandated territories acquired from Germany and Turkey after the First World War. Several of these territories were administered by the Dominion governments, not the Imperial government. These were subject to the supervisory power of the League of Nations and restrictions were placed upon the rights of the administrative power, with regard to guarantees of the rights of the indigenous peoples. The special international status of Palestine in this regard was particularly important and restrictive for the British administration. The third anomaly was the joint government maintained with other powers through condominium agreements. Thus the administration of the New Hebrides was shared with France and that of the Sudan with Egypt. In each of these anomalous cases British control was partial. Hence the impact of British ideas and organisation was far from uniform within the Empire. Extra-territorial extensions of Empire including the concessions of the Chinese treaty ports exhibited similar mixed traits (Western, 1985).

One of the major features of the structure of the British Empire was decentralisation with a strong element of self-government and indirect rule, both within colonies of European settlement and in protectorates with indigenous rulers. Self-government had been one of the distinguishing elements of the English colonial system from its inception, based on the precepts of English common law. In Virginia, when confronted with practical problems, the governor called a General Assembly in 1619 thereby establishing an institution which was to be emulated in numerous other colonies of English settlement (Robinson, 1957). Although subject to the control of a governor, usually appointed from London and at least nominally subject to the Crown, the colonial Councils and Assemblies were able to establish a high degree of local autonomy in matters of direct concern, such as land rights, dealings with indigenous peoples, regulation of internal trade and the raising and spending of local revenues. The solutions adopted to problems encountered in colonising a new land reflected the local environment, but also the cultural background of the immigrants themselves and the professional civil servants and soldiers of the Crown. The result was a wide variety upon a single theme, giving a degree of unity to the British Empi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1. Overview

- 2. The Metropole

- 3. Linkages

- 4. The Colonial Bases of Power

- 5. Settler Cities

- 6. Colonial Cities

- 7. The Rural Division of Land

- 8. European Farmlands

- 9. Imperial Landscapes

- Bibliography

- Index