![]()

1 Manna or monstrous regiment?

Technology, control, and democracy in the workplace

Martin Beirne and Harvie Ramsay

The question of technological change, as with most questions in the analysis of work and workplace relations, takes on a different cast depending on whether it is asked from the standpoint of capital and management, or from the view of labour and the employee. For management the primary issue is whether the productive benefits of technology outweigh its costs, and therefore how to realize and maximize those benefits. For labour, the chief concerns relate to the consequences of technological change for work experience and control – and even for the very existence of many jobs.

This book is predominantly concerned with the latter vantage point, with the consequences for labour of a particular set of technological changes created by information technology. However, the persistent and vexatious need for management to gain cooperation from the work-force, and related issues resurrected under the currently popular label of ‘human resource management’, leads to common areas of concern around questions of work content, experience and decision-making. Despite this overlap, though, the terms of this shared contemplation are rarely compatible, as evidenced by the contrasting claims for ‘involvement’ from management and ‘democracy’ or ‘participation’ from labour.

In the text, we use the term ‘information technology’, or IT for short, because the alternative, ‘new technology’, is inexact and potentially embraces all technical changes, not just those arising from the development and integration of microprocessor and communications devices. That said, the range of applications of silicon chip technology is now so great that a very wide range of contexts and effects must be considered, a fact reflected in the variety of contributions to this collection. While the information-handling capacities of the technology make it particularly direct in its impact on work which performs this function – namely office work – the ability to instruct mechanical actions has important implications expressed in the more popular, dramatic image of ‘automation’ and the ‘robot’, while the ability to read and process codes is transforming checkouts and stock control in the retail industry, for instance.

We should be clear that this book is not yet another attempt to map these general changes. Rather, it focuses on the question of workplace democracy (WD), and examines the relationship between IT and the various dimensions of WD identified below. In this, it brings together two related themes high on the current agenda of concern, since the political and socio-economic conditions of the late 1980s and early 1990s have seen a revival of attention to the condition and interests of the employee.

Another point to make at the outset is that the book is avowedly empirical in its approach, the emphasis being on the explanation of observed reality rather than the theorization of abstract possibilities. In this introduction, however, the wider concerns will be considered, and the contributions set in the context of that overview. To set the scene, we begin with an analysis of existing perspectives on the technology-democracy relationship.

DETERMINISM OR CHOICE?

Early studies of technological change tended to treat technology as something fixed, exerting a neutral ‘impact’ on work organization and experience – the machine as a deus ex machina. In its crudest and most expansive forms, this vision presents whole eras of social change as inevitable reflexes of technological development. This genre is represented on the left by restrictive readings of Marx and Engels, with communism as the ultimate and unstoppable end-game: The hand mill will give you a society with a feudal lord, the steam mill a society with the industrial capitalist’ (Marx 1847). From a different angle, the liberal right have recast the future to be read off from technology as pluralistic post-industrialism (cf. Bell 1973), while pessimists present more of a ‘1984’ image, especially given the potential use of IT for surveillance and monitoring.

Of course, these images of IT or other technologies as exogenous but potent moulds for social relations have been partly modified by analyses of the social production of technology itself. Thus when Carchedi (1984) argues that computers are unsuited for socialism, his argument is based on an analysis of computer technology as created under capitalist social relations, and so being designed as a tool of class domination. In a less sweeping fashion, Noble’s classic 1979 analysis of the management decisions behind the design of numerically controlled machine tools in the US after the Second World War combines the sense of structural constraint (through management control and the purposes management are required to serve) with the sense of process and agency, and the way these squeeze out what are in abstracto technical options.

Braverman, whose discussion of the ‘labour process’ inspired the work of Noble and has provoked the most active debates on work organization in the last decade and a half, presented his arguments concerning the deskilling effects of technical innovation as a critique of the evolutionary determinism of Blauner, Woodward and others (see pp. 9–11). ‘In reality,’ he insists, ‘machinery embraces a host of possibilities, many of which are systematically thwarted, rather than developed, by capital’ (Braverman 1974: 230). In order to distinguish between outright technological determinism and accounts like Braverman’s of systemic constraints on the application and design of technology, we will refer to the latter approach as social determinism.

Once the possibility of variation in the development and use of a given technical object is allowed, however, further exploration of this uncovers ever more complex sources of that variation in practice, and so casts in ever higher relief the apparent indeterminacy or, put in more active terms, the potential for social choice in technical design and its consequences. This has led Wilkinson (1983), like many others, to reject what he terms the ‘impact of innovation’ approach to analysing technological change, styling it as a depoliticization of the real processes involved. Differences of interest and deliberate choices by management in their own interests are obscured by the impersonalized view of IT, argues Wilkinson, especially when the new technology is presented as inevitable, as an ‘advance’, as something which it is in everybody’s interests to accept for the sake of keeping up with or getting ahead of the competition.

In this context it is interesting to consider the siting of sociotechnical analysis, as developed by the Tavistock Institute of Human Relations, among these approaches. This is worthwhile partly for illustrative purposes, but chiefly because socio-technical analysis has exerted a great deal of influence in the field, including recent approaches to computerized information systems (Beirne and Ramsay 1988).

On the one hand, socio-technical analysis advocates the ‘joint optimization’ of any work system, implying that machine and human variability are both adjustable to each other. In practice, however, it may be suggested that Tavistock consultants have always treated the technology as fixed, and sought to adapt recalcitrant human employees to it by varying working arrangements around the equipment (Hyman 1972; Kelly 1978, 1982).

This reflects two problematical aspects: the pollution of theorized possibilities by the consultancy role (which renders the replacement of equipment impractical as a suggestion to those who paid for it, and for the consultancy); and the conception of the social and technical systems as externally rather than internally related to one another. The eventual solution is also remarkably consistent, whatever the context. As Kelly (1978, 1982) has recognized, it comes down to the practice of mounting a critique of the set views of Taylorism only to substitute a different ‘one best way’ of group working. The socio-technical tradition is after all one of adapting to the ‘impact’ of technology: ‘a change is required in the work culture from a man-centred [sic] to a machine-centred attitude – a machine culture’ (Trist et al 1963: 259). Of course social choice accounts themselves recognize more than one source of variation in the development of given technologies. First, there are those beyond the control of actors within the organization – namely, the environmental conditions under which IT is adopted which dictate the degree of room for manoeuvre, such as the intensity of cost and/or quality competition, for instance.

Second, there are the strategic choices open to management (Sorge and Streeck 1988, Child 1985, Friedman 1977), who may emphasize a variety of deskilling or enskilling potentials of IT in their recruitment and labour utilization policies. While certain options may be more likely under particular conditions (such as the pressures created by the different product cycle phases of manufactured goods, for instance), these authors none the less emphasize that alternative potentially viable choices are always open to some degree.

Third, there are variations introduced by labour resistance to management policy, and the subsequent negotiation or battle for control of how IT is operated. This contestation of outcomes is often elided from managerial writings, and sometimes from labour process accounts.

Unfortunately, social choice on these combined dimensions is often taken to extremes, becoming so dominant in causality that technology appears almost infinitely elastic in its nature, barely sustaining an existence in itself. For instance, in one widely used textbook on organizations it is suggested that ‘we should not be studying technology at all … we should instead be analysing managers’ beliefs, assumptions and decision-making processes’ (Buchanan and Huczynski 1985: 221). This reductionism is also threatened by recent attempts, stimulating and insightful though they often are, to analyse technology as a ‘social construction’ (for example, Bijker et al. 1989).

In a useful corrective to this, it is riposted that the ‘technology baby should not be ejected with the determinist bathwater’ (to slightly rephrase Clark et al. 1988 and McLoughlin and Clark 1988). They observe that many of those who have set out to modify the simple causal model running from technology to social relations have none the less noted elements of ‘constraint’ or ‘rigidity’ in a given technology. Moreover, studies of technology show that just as it is not produced in a social vacuum before entering society, so it also develops from past technological and scientific understanding, preventing there being scope for infinite variation and recasting at any given moment in time. Technologies can also prove faulty, especially in the early years, and this imposes significant unintentional and unpredictable effects on work practices beyond the control of anyone in the innovating organization.

In any case, much new technology (whether microprocessor based or not) is itself produced by a few firms and sold as a package to others, seriously limiting the scope for local management or employee manoeuvre – a phenomenon particularly evident over many years in the computing field with the dominance of IBM, for instance. In a number of ways, then, technology does arrive from outside and has an ‘impact’ from the point of view of management or employees in a given organization. Ironically, an emphasis on the social production of technology may highlight, in important respects, the limitations for choice at the local levels by those applying it or experiencing the consequences thereof.

While social choice approaches remain more flexible and persuasive than determinist ones in our assessment then, the limits and constraints of choice remain in need of being charted. Many writers present cautious assessments of ‘potentials’ created by microprocessor technologies, for networked and more open access to data in an information system (Mumford 1979, 1983), or for diagnosis and reprogramming by operators of robots or CNC tools, for example (Jones 1982). But the slippage from this to insistence on the inevitability of such change is often swift and near-total. The sense of social structure as contradiction and constraint for such policies is abandoned too readily, as (to anticipate) our review of real-world outcomes demonstrates.

OPTIMISM OR PESSIMISM?

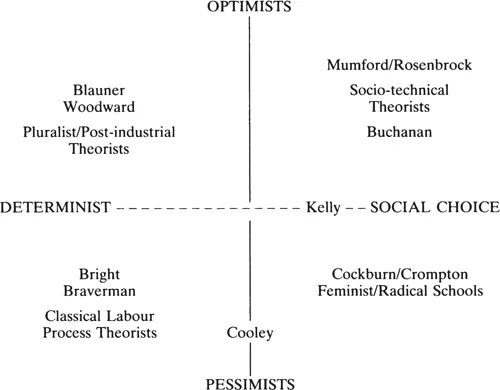

So far our discussion has provided glimpses of positive and negative implications for workplace democracy, but the determinist and social choice perspectives both contain contrasting assessments on this score. To get to grips with the issues of particular concern to us, then, we must introduce a cross-cutting distinction between optimistic and pessimistic predictions for IT users. If we persist for a moment in treating this (and the determinism/choice dimension likewise) as a straightforward continuum, it becomes possible to produce a simple diagram (see Figure 1.1) onto which it is quite instructive to map different commentators. The result shows how alliances may emerge on one dimension between writers of markedly different persuasion (a picture which should be enhanced if we could superimpose the third dimension of political standpoint).

Optimism or pessimism may be seen as shaped by either technological determinism, or (in a manner perhaps a little less narrowly determinist) by what we have called social determinism. Thus the mapping of approaches on Figure 1.1 reflects predictions of the enhancement or debilitation of workplace democracy derived from both arguments about the inherent properties of IT itself, and of the degree of structural constraint in the settings within which it is produced and introduced.

Figure 1.1 Images of IT

This distinguishes a writer like Cooley (1980) from someone like Rosenbrock (1982), for instance. In many respects these authors offer a similar debunking of the ‘expert’ ideologies of systems design that justify non-participation and minimal job discretion for the user. However, the former locates this campaign for alternatives within an awareness of the wider structures of capital imperatives and management objectives which he sees as promoting the low-skill options, whereas the latt...