- 218 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Originally published in 1992, this study looks at the ways in which company and campus can co-operate to spread the risk and cost of research. It analyses joint ventures in an international context, focusing particularly on the USA, France and Japan, comparing their management strategies with the UK in a variety of industries. It discusses issues such as the brain drain and the growth of science parks, looking at the most succesful industrial policies. With its focus on technology transfer, joint ventures and strategic management this book will appeal to the practising manager as well as the academic.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Company and Campus Partnership by D. Jane Bower in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Spreading the risk of the company R&D portfolio

New product development is becoming more costly. Markets are becoming daily less predictable. The changes are driven by increasing competitive pressures, technological change and shortening product life cycles.

Technology-based companies, with their long lead times and high R&D costs are looking for strategies which minimise the escalating risks. The same pressures dictate that in order to survive they must stay at the forefront technically. New products are becoming more sophisticated; often they require inputs from several advanced technologies for their development and manufacture. This creates a dilemma. It is imperative to control costs and time horizons; at the same time there is the conflicting need to span an ever-greater technical range.

To reconcile these demands requires a significant modification of traditional strategies. In all industrialised countries and in all sectors, many companies are employing new approaches to address the problems.

HOW COMPANIES INNOVATE

Technology-based industries have traditionally fallen into two major categories in terms of the way they acquire new technology. These have been described as the ‘assemblers’ and the ‘producers’ (Barabaschi 1990).

The first are the companies which assemble the product from components made elsewhere. The car and aerospace industries fall into this category. Novel technology generated by subsystems contractors is integrated into the finished product. Rolls Royce, the British aeroengineering company, is typical of the assemblers. Its supplier strategy and R&D strategy are intimately linked. Its skill in co-ordination of in-house and supplier development activity are regarded as one of the key factors for the success of the last decade (FoE 1991).

Chemical and pharmaceutical companies, which manufacture the whole product, fall into the second class. Traditionally they have developed their products entirely in-house, together with the pro cess and manufacturing technologies.

For the first group, the dominant expertise has been in design and integration; for the latter, design and manufacture. The difference has never been absolute. The ‘assemblers’ may develop some core technology in-house, and indeed this is very important in companies like Rolls Royce. The ‘producers’ have always used some imported technology in their production processes, and have had to exert a high degree of expertise in integration of functions in product development. However, there has been a substantial, perceived difference of approach for quite a long time.

Now these distinctions are being progressively blurred. New products and processes often involve the integration of several technologies. For companies accustomed to full inhouse development, the burden of maintaining a competitive edge in several technologies is becoming unmanageable. It makes no sense to be reinventing the wheel daily, at great expense, if the required technology, already invented elsewhere, can be bought in at a lower cost. There is not enough time in a highly competitive environment to acquire an in-house capability in a new technology before making use of it. Nor does it make sense to defocus the company’s research effort over too broad a range of enabling technologies.

At first sight this seems straightforward, but in reality this is by no means the case. It requires companies to ask themselves the key strategic question ‘What business are we in?’ more searchingly than ever. It also requires them to answer it with uncompromising honesty about their strengths and weaknesses. This is easy enough when, for instance, a pharmaceutical company is installing a new information system. This requires acquisition of systems and technology developed elsewhere, even if it is customised for the company. The decision to buy in does not cause any profound conflict. The technology required and the function it fulfils have never been perceived as a special area of expertise for the company.

It is much more difficult when the same company must ask itself whether the fundamental technology for making and mass-producing a new product must be bought in, or else accessed through a joint venture with a specialist R&D company. This is the situation which the traditional large drug companies have had to address in the last 15 years. Previously they had regarded the invention, development and much of the production process technology of patented drugs as their core business, and their ability to carry out full, inhouse development was a source of pride and strength. Now they are increasingly acknowledging that while competitive pressures are requiring them to include a significant proportion of extremely novel drugs in their portfolios, it is not cost-effective to try to make all of them in-house. For a variety of reasons, discussed below, it is preferable to source a proportion of their R&D requirements from outside the firm.

R&D risk

There are several sources of risk in product and process development. The company must continually come up with good new product ideas. During the long period of development, cost overruns, time overruns and changes in the external market environment can all add to the uncertainties of revenue projections.

All projects do not necessarily share the same risk profile. Thus one desired objective is to construct a portfolio whose overall risk is minimised by offsetting the risks inherent in the individual projects (Twiss and Goodridge 1989; Bower 1992). The other objective, of course, is to have a stable of projects which will yield an acceptable and steadily increasing level of profit.

How can these aims be reconciled? The company must first identify the nature of the risks it faces, and then consider the alternative ways projects might be organised to control them.

Controlling the risks

What are the risk factors which must be balanced to optimise a company’s R&D portfolio? Let us look at them individually, and at the solutions that are commonly adopted.

1 The product doesn’t work

This was the problem which led to the abandonment of the British electronics company GEC’s military surveillance plane which was to rival the American AW ACS.

Technical failure is a risk that is highest at the early stages of development. The maximum risk to the company is when too many projects are at the same early stage. The portfolio should include projects at all stages, from the idea to the finished product – thus there will be a continual flow of new products. If one product fails, the company’s position will be relatively protected. Ideally, the company should be involved in as many projects of equivalent promise as can be accommodated within the limits of the budget.

2 Another company brings a better product to market

Speed of product development reduces this risk, as does having as broad a range of products as possible, targeted at different niches.

3 The market may change and demand fails to materialise

This again requires speed and a range of products. Acquisition or licensing of finished products is another possible response.

4 Cost and time overruns

Joint ventures, options to develop alternative products, and a wide enough range of projects to minimise reluctance to axe the less promising, are risk-reducers. Purchase of finished technology removes this risk altogether, at a price.

5 Innovative new enabling technology developed elsewhere threatens the company’s competitiveness

This has happened repeatedly in recent years. Many of the most spectacular cases have involved innovative uses of microchip technology. Banks have reduced transaction time and costs. Supermarkets have introduced computerised stock control systems. These changes have permitted quantum leaps in company performance. The possible solutions for competitors are to obtain access to the new technology by licensing etc., or to devise or acquire an even more novel technology.

6 Profitability is threatened because market access is restricted

This has often been the case with Japan, which constitutes a large part of the potential world market for most sophisticated products, but which is notoriously difficult to enter. A common solution is to have joint venture partners who are able to access the part of the market which is closed to the company.

R&D PORTFOLIO STRATEGIES

Companies are responding to these challenges by changes in the way they construct the R&D portfolio. The objective is to reduce average project development time and maximise the total number of projects the company controls, without significantly affecting costs. The company wishes ideally to minimise risks in all categories. The optimum R&D portfolio, then, will contain a number of projects at different stages of development. They will address different market niches, although within the range of the company’s other capabilities in marketing, production, etc. They will employ the most effective technologies, whether in-house or acquired by some means. Preferably, there will be a larger number with shared risks and rewards rather than a smaller number with all the risk and all the rewards remaining with the company.

CONSTRUCTING THE OPTIMUM PORTFOLIO

In constructing a portfolio of product development projects, strategic decisions must be made about the number of products that must be on sale at any one time, the range of markets addressed, and the frequency of new product introduction. Internal factors such as the company’s in-house capacities, projected growth rates, and required rates of return will influence decisions. The nature of the competition must also be addressed.

The company will have to consider its dependence on external suppliers. This may be for only the most basic raw materials, but there will have to be some assessment of potential problems of ensuring the continuity of these inputs. Where there are abundant alternative sources, there may be no impact on strategic thinking. If, on the other hand, there is a requirement to source relatively complex components, which may require some customisation by suppliers, or a requirement to access technologies developed elsewhere, then considerations of availability and continuity of supply arise which must be accommodated in the product development strategy. There may be a need to make substantial investment in relationships that are crucial to the success of the strategy (Håkansson 1987).

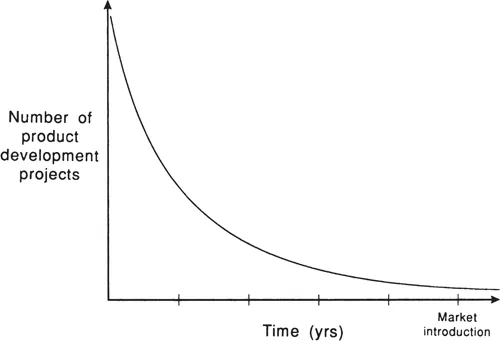

Figure 1.1 Constructing the optimum portfolio

The optimum portfolio of product development projects will have several characteristics that will ensure a steady flow of products to market. It will contain projects, or options to acquire projects, at all stages of development. There will usually be more at the very early stage than at the near-market stage. Development costs increase exponentially in the course of a normal project, thus it costs relatively little to have a large number at the earliest stage. This allows the company to choose the most promising from among several possibilities before costs start to rise steeply.

All projects need not be in-house – acquiring rights in a project under development in another company can be an acceptable way of retaining an option to part or all of an external project.

At later development stages, development costs escalate. The more promising projects are retained. Again, these may be entirely in-house, or they may involve external partners. Where external partners are carrying part of the risk of the project through investing their own resources, less resources are required from the other partner, reducing its exposure to risk from that particular project. This frees some resources for another project, allowing the company to spread its resources over a larger total number of projects. The potential returns from any one will of course be reduced, but the risks of ultimate failure are also reduced in proportion to the increased number of projects which the company can retain rights in. If one fails to pass the technical review at a later stage of development, more resources can be allocated to the remaining projects. If one fails after market introduction, it is a smaller fraction of the product portfolio and thus less disastrous.

Accessing externally developed technology through licensing or through joint R&D projects is increasingly being treated as just a special case of the client/supplier relationship (Spriano 1989; Håkansson 1987; Pisano 1991; FoE 1991). The supply in these cases is novel technology, technological capability, or even technologically novel products.

Planning to fulfil these technological needs can meet with difficulties on several levels. The first is the reluctance of the company as a whole, and of individual departments, to accept the need for any increase in dependence. It is a blow to the collective corporate ego and can create a sense of vulnerability. Companies may choose to avoid the issue by setting up an in-house capability; sometimes this may be appropriate, but it may on occasion be more costly than other alternatives.

The second level at which problems may arise is that of managing the interface with the supplier. Studies of the efficiency of, for example, Japanese supplier relationships, have underlined the considerable costs incurred in organisations where this interface is mismanaged. Where the relationship to be managed has been created to carry out a joint R&D project, the interface is so complex that organisations often choose to put it into a joint venture company.

The complexity of management problems is at its greatest when several very different organisations are jointly involved in a single product development project. This is the case with projects to develop drugs where several small and large companies in different countries may play complementary roles. Here a group of joint venture agreements are signed, with one of the companies, usually the owner of the intellectual property, acting as one of the two partners in each individual joint venture, but in combination with a different partner for each major geographical market. The other partners contribute finance and often have responsibilities for gaining regulatory approval in their home markets. In return they usually gain marketing rights for the product, restricted to their own market. National regulatory organisations must...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Figures and tables

- Acknowledgements

- List of abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Spreading the risk of the company R&D portfolio

- 2 The new approach to company/campus joint ventures

- 3 Technology transfer on the US campus

- 4 Technology transfer from UK research organisations

- 5 Science parks and technology transfer

- 6 University/industry liaison in other countries

- 7 The university and the company – different cultures

- 8 The environment for innovation in the UK and the USA

- 9 The track record to date

- Appendix

- References

- Index