- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Revival: The Mind In Daily Life (1933)

About this book

This book is an elementary exposition. It contains no more technically than seemed readily understandable by the intelligent layman and the medical student desiring a merely general introduction to modern views on the motives of human conduct and the mental processes of which that conduct is the expression.

Part I gives some account of processes and motives that are universal and therefore normal. Part II is written from the angle of the physician who sees the results, always common but nowadays more frequently discussed, of the miscarriage of the normal development of human beings as such.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Revival: The Mind In Daily Life (1933) by R. D. Gillespie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

THE MIND IN DAILY LIFE

PART I

PSYCHOLOGY OF THE NORMAL

CHAPTER I

Development of the Emotions and the Self

IF there is one fact on which the various schools of psychological thought are agreed, it is of the great importance of the period of infancy and childhood in determining the subsequent character and behaviour of the individual. It is partly on account of the unanimity in this respect that any discussion of first principles must begin with a description of the development of the individual mind from the days of infancy. Bertrand Russell, for example, who is in the distinguished line of philosophers whose writings have concerned themselves with the education of the young, believes that if care is taken in character-building during the first six years, the rest of the time of pupillage can safely be devoted to other things.

The new-born child is little more than an automatic machine in his performance, though so vastly different in his potentialities. On his first entrance into the world the cold air stimulates the skin and causes the child to utter a cry with its first breath. Some philosophers have ironically interpreted this as a howl of protest: others as one of the manifestations of the feeling of distress supposed to be experienced during the ordeal of birth.

It is probably neither, being but the automatic kind of act we have alluded to. If because of a difficult birth there is so much asphyxia that the reflex nervous mechanism is dulled, and the child fails to cry, some mild slaps applied to its buttocks make him do so. A day or so later he is put to the breast, contact with which after a time causes the lips to make sucking movements. The bowel and bladder empty directly they are sufficiently distended, without deliberation or respect of persons. Many of the actions of the new-born child, in brief, appear to be immediate responses to rather simple stimuli impinging on its internal or external bodily surfaces. But there are other activities which appear quite early, which in later life are usually classified as “mental” activities, i.e. occurrences appertaining more to the individual as a whole, considered as a person among other persons, than to parts of the body and its functions. Such activities are those which are held to indicate fear, rage and love—three examples, in other words, of what we call the emotions. Emotional reactions are usually considered to be inborn. Of all the emotions known to us, signs of only the three mentioned could be detected in a very young infant by J. B. Watson, who was, curiously, the first to make a point of investigating the matter by direct observation of very young children. Previous writers had simply assumed that all the emotions known to adults had existed in some form from the beginning, and tabulated a list of as many as they felt they could distinguish by introspection (i.e. by examining their own minds). These arm-chair writers did not trouble to confirm their speculations by watching young children to detect the epochs when the various emotions first appeared in them. The question is whether what Watson observed in the newly born are emotions in the usual adult sense at all—whether there is more than a mere nebula of conscious feeling attached to them, and whether they have any ‘meaning’ in the sense of having any experiences associated with them in the child’s mind. Watson’s methods were to observe the reactions of very young infants, of a few days to a few weeks old, to certain conditions of a simple kind. When the infant is suddenly bereft of its support, or when a loud sound is made near it, it shows the outward signs of fear, and presumably something comes to pass in its rudimentary consciousness. When its movements are confined and restricted it shows the signs of rage, but they consist of diffuse movements without any co-ordinated aim. But in addition to the fact that the baby’s experience is so limited at this stage that few associations can have been formed to give meaning to the reactions, we know also that his brain, and especially those regions of it in which associations between new experiences and memories of old ones principally have their seat, are imperfectly developed (Chapter II). Furthermore it has been shown that all the manifestations of rage can be elicited from a dog in which all the front part of the brain, down to what is called the ‘between’ brain, has been destroyed. This indicates one of the possible pitfalls of psychology, that one must be cautious in attributing to other persons or animals the same conscious mental experiences as ourselves, merely because they appear to behave as we would do if certain experiences were happening in us. The dog in the condition mentioned, although it exhibited all the signs of rage, could have little or no consciousness of anger, as consciousness in the higher animals appears to be associated mainly with the action of the superficial layers of the brain, which in this animal had been destroyed. It is similar with infants, although in them there is some consciousness:

(a) APPRECIATION OF THE EXTERNAL WORLD

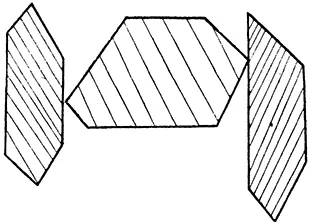

The child’s mental life in general and not only in connexion with these emotional reactions is necessarily very limited at this time. Nearly all of its experience is new, although of course the old steadily increases in quantity and furnishes material for associating with each new experience, so that meanings are always being acquired and enriched. It used to be held that the infant’s or young animal’s experience at first consisted only of simple sensations from within and without—of smell, taste, touch and hearing at first and later of sight, and that these sensations were amplified later by association with similar experiences or with memory traces of previous ones into ‘perceptions’. But the views of psychologists have lately changed, and it is now believed that what the infant first obtains in his consciousness is a general impression, blurred at first no doubt, but gradually discriminated into its separate components as time proceeds, i.e. that a complex perception and not a fairly simple sensation is the primary experience. This conclusion has been arrived at partly by experiment with animals. It was found that if the food of hens was so arranged that palatable morsels were placed on a piece of grey paper and less palatable morsels on a piece of darker grey, the hens soon learned to make immediately for those on the light piece; but if two new shades were substituted with the same degree of difference between them as the first pair the hens still made for the lighter piece, i.e., it was not the particular shade that had led them to the correct place, but the contrast between the shades; it was as if the hens perceived the pieces as a whole and not singly. Similarly with the perception of certain forms by adult human beings. Köhler gives the following example. Here is a series of straight lines, regularly arranged.

FIG. 1

Printed thus they are not seen as a mere series of straight lines but as sets of pairs, as if each pair represented a discrete object, related, however, to the others, as e.g. each stake in a fence to the others. It might be replied that the adult had been educated by experience to see them as stakes, but if we take the following figure the result is the same. We do not see the K as such until our attention is drawn to it.

FIG. 2 (after Murchison’s Psychology of 1925).

A simple diffuse experience of the sort just described is called a perception. This is now supposed to be the process by which the child perceives the outer world as presented to its senses—by a perception of the whole settings of things, followed by a progressive differentiation of their component parts. An entire system of psychology has been built up on such observations, and has been called the ‘psychology of wholes’ (‘Gestalt psychology’). The very simplest experience, e.g. a flash of light, which anyone can have, is called a sensation; but it is doubtful if there ever is a pure sensation. There is nearly always an admixture of memories of previous experiences, giving a percept (i.e. sensation plus associated simultaneous previous experiences). When an experience resembling a sensation or a perception arises in consciousness without external provocation one speaks of an ‘image’. When the elements of several images (internally revived perceptions, as one believes them to be) coalesce to give a new image of something never previously experienced by stimulation from without, we have an ‘idea’. The term ‘concept’ is technically reserved for a group of associated ideas giving us a systematic notion of something. The growth and development of perceptions, images, ideas and concepts constitutes the intellectual aspect of the development of the mind. The individual mind must be considered always as a whole; and the separation of intellectual from emotional development in describing its growth is only made for the sake of convenience; there is in a sense an emotional as well as an intellectual aspect to every occurrence. But it is necessary for descriptive purposes to deal with the emotional and intellectual aspects separately. It is the emotional side which is more important in the young, and in fact at all ages, from the point of view of health and disease. Consequently it will be necessary for our purpose to discuss the emotional aspects of mind in more detail than the intellectual.

The Nature of Emotions. It will be remembered that Watson could decipher the signs of only three principal emotions in the infant—love, fear and rage. But in children and adults there are many more emotions than these, such as happiness, sometimes called ‘elation’, sadness, technically called ‘depression’, pity, hate and the like. The list of such emotions compiled by McDougall is probably the best known. He classified emotions into primary, secondary and derived groups. The primary emotions, McDougall considers, are those which accompany the operation of an instinct. An instinct is defined as an inborn mode of response, being purposive although the organism has had no previous experience in the given direction to guide it. According to McDougall there are six primary emotions associated with the operation of six primary instincts. An analogy from a topic discussed in the chapter on the physiology of the central nervous system suggested to McDougall that an instinctive action may be represented as taking place through the medium of some structures in the central nervous system whose pattern is that of a reflex arc (see Chapter V). It is in association with the workings of the central portion of this reflex arc of instinct that emotion is supposed to arise. Such is McDougall’s schematic image of the physiological basis of emotion and instinct. The value of a ‘reflex arc’ theory of any kind of mental activity instinctive or acquired is extremely doubtful, since the relation of mental process to physical process in the brain is pure guess-work: but this theory of McDougall’s has been widely adopted. It is held by some in addition that the more resistance or ‘friction’ that is encountered by the passage of an impulse along McDougall’s reflex arc, the more definitely the emotion is felt.

In this theory the emotion is the reflection in consciousness of partially obstructed physiological process in the central nervous system.

There is an alternative theory, that the emotions consist essentially in the conscious reverberation of physiological processes occurring outside the nervous system, in the heart, lungs and viscera. This view was propounded almost simultaneously by Professor William James in America and by Professor Lange in Germany, and is consequently known as the James-Lange hypothesis. As James put it, ‘When we see a bear we are frightened and run, but in fact we are frightened because we run….’ If we cry and feel sad, in James’s opinion then we feel sad because we cry. This peripheral theory of the basis of emotion has aroused much discussion, but at present as the result of experiment and reflection does not find much favour. The experimental evidence, and such evidence as it is possible to procure from the study of disease, is on the whole against it. If it were correct, the people who complain, as some do, in mental disease that they no longer have any capacity to feel emotion should have no visceral sensation, but in practice it is found that such people do have visceral sensation. Even in the case of one woman who complained not only of complete lack of emotion but of visceral anaesthesia as well (she felt neither hunger nor thirst, for example), I found that the viscera reacted in the usual way to the appropriate stimulation, namely distension, conscious discomfort or actual pain being produced by a small balloon placed in the oesophagus and inflated.

The modern view is that whatever the exact physiological basis of an emotion may be, its physiological focus is in the central nervous system, but that from this focus there spreads a nervous disturbance which results in a temporary change in the other parts of the body, especially in the viscera. The accompanying conscious experience is the emotion as we know it. It has not been found that there are specific changes in the body for each emotion. Very different emotions such as fear and joy are apt to produce very similar or identical body changes. Some of the bodily effects are well known to every one, for example the trembling limbs of fear, and viscerally the more rapid action of the heart. There are of course changes in facial expression also; but here again there is not the specificity which we might expect. This can be best shown by exhibiting a series of photographs of the faces of persons in attitudes of fear, rage, joy and the like to any one and asking him to name the various emotions depicted. As a rule the answers are correct for little more than 50 per cent of the photographs.

To sum up; an emotion includes a conscious component, e.g. a feeling of fear, plus a physical disturbance of the body, especially of the viscera (heart, lungs, intestines, etc.). The physiological processes involved will be discussed in Chapter V.

Such is the barest outline of the psycho-physical equipment with which every child is endowed for the manifestation of its emotions : but the emotion as such is of comparatively slight importance. What matters is the specific situations in which emotions are displayed; and this implies the continued existence of a definite individual, i.e. a being with a conscious and unconscious more or less organized set of standards, aims and habits. It is necessary to consider, therefore, the development of the individual personality which gradually learns to feel and behave in certain ways as the result of constantly accumulating experience.

(b) DEVELOPMENT OF THE SELF; AND OF THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN SELF AND THE OUTER WORLD

One of the essential preliminaries for the child’s development of a separate personality is its gradual recognition of a distinction between itself and the outer world, between a ‘me’ and ‘not-me’. In the earliest days there is no possibility of such a distinction; the infant is not conscious of itself as a separate entity. But gradually the child becomes aware of a number of things which do not so immediately respond to its wishes, in contradiction to the things that do. For instance, he encounters resistance in some directions and not in others—his arm moves at will, but the wall which his arm touches does not move at his command. There comes also a differentiation from other people. At first the child and its mother are virtually one. It is as if she were a part of the child and the child still part of her. This is the so-called ‘magic stage’ or stage of omnipotence in development, in which the child, although itself utterly helpless, yet finds everything done for it. He is, as it were, a king and the environment (the mother or nurse) is enslaved. It has been suggested that the Golden Age after which so many of us hanker, is a reminiscence of this happy state. But there begins to be a less absolute dominion; every wish is not gratified; there are more and more denials. The ‘not-me’ makes itself felt more and more. There is an addition^some-thing intermediate between the child’s more immediate self and the external world. This is the child’s own body and limbs; they respond to his wishes, he feels a peculiar intimacy with them; but they are visible and external; they are not the most intimate ‘me’. He gets a certain pleasure out of these sensations from his body, especially from certain parts of his body, for example the mouth in sucking. Hence he feels the withdrawal of the breast as a serious deprivation, rebels and may be consoled with a comforter. Rebellions of this type, if not well managed, often leave their mark upon a child, to an extent that is realized only when the morbid attitudes of older children and adults come to be studied in detail.

Prolongation of what has already been designated the ‘omnipotence’ phase, fostered by a too fond parent’s natural inclination to indulge the reluctance of the child to leave this easy-going state, is what is commonly called ‘spoiling’ the child. Paternal behaviour that would be normal in the ordinary early phase of helplessness becomes grotesque when prolonged in this way. The number of mothers who continue to bath their children, especially their boys, of 10 and 12 years of age is surprising. I have even known one mother who supervised the daily bath of her seventeen-year-old son. Minor but equally pernicious examples of this unwise stretching-out of the phase of complete dependence are well known to every one; but it is not generally realized that prolongation of any detail of any stage of the development of independence and of the abandonment of childish comforts may leave a mark which can have effects in after life on that part of the personality that is usually called character. A comforter— to take a very simple example—is to be avoided not merely on physical hygienic grounds, but because if retained after weaning it represents babyhood and a point at which development has not kept pace with the rest of the process of ‘growing up’.

An undue prolongation of breast-feeding itself can, at least in our community where prolonged lactation is not the rule, help to keep alive too much dependence of child on mother; and may also in extreme cases nourish feelings of shame in the child, who is apt to realize that although he cherishes it, breast feeding is a mark of babyhood. I remember one man who was more than usually attached to his mother, but who among other feelings of his own insufficiency remembered with shame that he was still occasionally put to the breast when he was as much as four years old, and how this fact was discovered and ridiculed by his playmates.

On the other hand, if a normal phase of dependence is too abruptly or too soon cut short, then there is some evidence that the avoidably deep feelings of loss so occasioned may persist as a general psychological disposition, either as an under-current of sadness and pessimism, or as resentment, which will often manifest itself as undue stubbornness. The ‘not me’ is felt to be peculiarly unkind and the child feels friendless ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Part I Psychology of the Normal

- Part II Errors in Mental Development

- APPENDIX I : The Autobiography of one who ultimately developed a Mental Disorder

- APPENDIX II : The Art of Study : Its Principles and their Application

- Index