- 245 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The goal of this book series has been to provide an overview of rhabdovirology as a whole (including an appraisal of current research findings), suitable for students, teachers, and, research workers. To realize this goal many of the research leaders in the different disciplines of rhabdovirology were asked to contribute chapters.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Rhabdoviruses by David H.L Bishop in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

ADSORPTION, PENETRATION, UNCOATING, AND THE IN VIVO mRNA TRANSCRIPTION PROCESS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. | Rhabdovirus Replication in Cell Culture |

A. Adsorption | |

1. Infectivity | |

a. Reduction of Infectivity | |

b. Neutralization of Infectivity | |

c. Enhancement of Infectivity | |

B. Entry into the Cell and Uncoating of the Virion | |

C. In Vivo mRNA Transcription | |

1. Messenger RNA Species | |

a. Polyadenylation | |

b. Nucleotide Sequences, Capping, and Methylation | |

2. Primary Transcription | |

3. Secondary Transcription | |

4. Transcription of Temperature-Sensitive Mutants In Vivo at Nonpermissive Temperatures | |

a. VSV-Indiana | |

b. VSV-New Jersey | |

D. Proposed Mechanism of VSV-Indiana Transcription | |

Acknowledgments | |

References | |

* Dr. Repik’s affiliation at the time this chapter was written was the Department of Microbiology, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois.

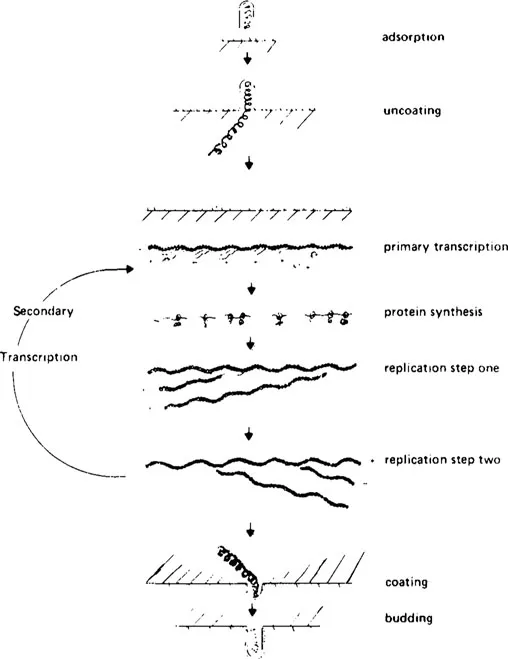

FIGURE 1. Schematic representation of a productive infection of cells by VSV-lndiana. (From Bishop, D. H. L. and Smith, M. S., The Molecular Biology of Animal Viruses, Vol. 1, Nayak, D. P., Ed., Marcel Dekker, New York, 1977, 176. With permission.)

I. RHABDOVIRUS REPLICATION IN CELL CULTURE

Although many rhabdoviruses have been isolated from different sources, only VSV-lndiana has been characterized well enough to allow us to draw conclusions concerning its replication cycle. Infection with rhabdoviruses can result either in a productive infection whereby the majority of progeny virions are infectious, or in an abortive infection which results in the majority of progeny virions being defective (noninfectious). The latter type of infection can be caused by the presence of defective interfering particles or by nonpermissive conditions during the replication cycle and will be discussed in greater detail in succeeding chapters. One should be aware that both infectious and defective progeny virions can be produced simultaneously within the same replication cycle.

A productive infection of cells by VSV-lndiana can be divided into several steps as shown schematically in Figure 1. These are

1. Adsorption or attachment of the virus to the cell membrane, followed by penetration into the cell and uncoating of the virion to expose the viral nucleocapsid

2. Transcription of the viral genome into mRNA species by the transcriptase enzymes present in infecting virions (primary transcription)

3. Synthesis of viral proteins (including more transcriptase enzymes)

4. Replication (probably occurring in two steps) of progeny genomes from the infecting parental genome

5. Further rounds of transcription from progeny viral-like RNA (secondary transcription), protein synthesis, and replication

6. Progeny virus assembly and release by budding

A. Adsorption

Attachment of rhabdoviruses to susceptible cell membranes involves an initial association between the viral glycoprotein spikes and some as yet undefined host cell receptor(s). The viral G protein is the sole constituent of viral glycoprotein surface projections (spikes) which stud the surface of the viral envelope. Studies have been conducted which show that the spikes are iodinated by oxidation with lactoperoxidase or chloramine T,1,2 confirming the fact that most of the G protein is exterior to the envelope. Electron micrographs taken of cells infected with VSV and rabies viruses clearly show that the virions attach to the cell surface via their glycoprotein spikes,3, 4, 5, 6 with attachment noted to occur on all surfaces of the virion — the rounded end, the flat end, or on either side.

The number of adsorbed rhabdoviruses increases linearly with time during the first 30 min of infection at 37°C, and is also able to occur at 4°C.4,6, 7, 8 Vesicular stomatitis virus adsorbs to cells inefficiently and, after adsorption, washed monolayers of infected cells desorb 20 to 40% of their virions within 30 min at 37°C.7, 8, 9 There is also evidence that viruses differ in their efficiencies to adsorb to or desorb from different cell types. By calculating the amount of RNase resistance acquired by 3H-labeled infecting VSV genomes, it was found that VSV adsorbs better to BHK cells than to mouse L cells; adsorption was least efficient on chicken (CEF) cells. By the same token, desorption was found to be less pronounced from BHK or L cells than from CEF cells.7, 8, 9, 10

1. Infectivity

Since the viral glycoprotein spikes play a key role in the attachment of the virion to the host cell, anything that can alter their conformation or destroy their integrity can affect the process of adsorption and, therefore, the infectivity of the virus.

a. Reduction of Infectivity

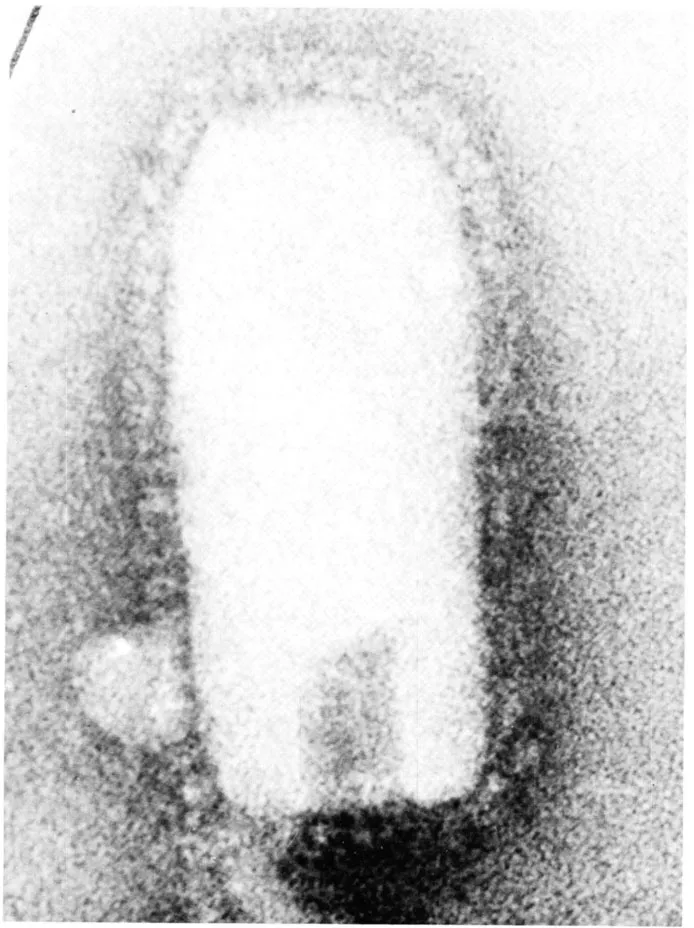

Treatment of intact virions (Figure 2) with proteolytic enzymes removes all but a very small fragment of the G protein (fragment mol wt of approximately 7,000 daltons11,12) resulting in the production of spikeless virus particles (Figure 3) which retain only a small fraction of the original infectivity.13, 14, 15 It has been found that different proteolytic enzymes have different effects on various rhabdoviruses. Using several strains of VSV, Bussereau et al.15 studied the effects of trypsin and chymotrypsin on the infectivity, morphology, and antigenic properties. Each enzyme reduced the infectivities of VSV-Indiana and VSV-New Jersey by roughly 10,000-fold, but did not affect the infectivities of VSV-Brazil and Argentina and had minimal effect on the infectivity of Cocal (Table 1). Electron microscopy of the enzyme-treated virions and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of their viral polypeptides demonstrated that the enzymes removed all the glycoprotein spikes of VSV-Indiana; however, approximately one third of the spikes of VSV-Brazil were resistant to enzyme action. Similarly, it has been observed that Chandipura retains most of its infectivity after treatment with bromelain,144 although this same virus loses all its G protein and essentially all its infectivity upon treatment with Pronase® (Table 2).

FIGURE 2. Electron micrograph of a VSV-Indiana whole virion negatively stained with sodium phosphotungstate. The particle is approximately 180 nm long, 65 nm wide, and is covered with spikes 10 nm in length. The sample was stained and photographed by Dr. R. W. Compans. University of Alabama Medical Center. Scale: 1 cm = 15 nm.

The infectivities of such spikeless preparations of rhabdoviruses can be restored to varying degrees by homologous and heterologous glycoprotein extracts (Table 2). The glycoprotein extracts contain the viral lipids and appear to be composed of mixed micellar structures (containing both lipids and protein),16 the lipid portion forming the vesicle and the glycoproteins studding the surface (Figure 4). No infectivity could be detected among any of these extracts. As seen in Table 2, the greatest increases in infectivity resulted from mixing spikeless particles and glycoprotein extracts generated from rhabdoviruses of the VSV subgroup (VSV-Indiana, VSV-New Jersey, or Chandipura spikclcss panicles plus VSV-Indiana or New Jersey glycoprotein extracts). The fact that the Chandipura glycoprotein extract appeared to be much less efficient in restoring infectivity w...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Chapter 1: Adsorption, Penetration, Uncoating, and the In Vivo mRNA Transcription Process

- Chapter 2: The In Vitro mRNA Transcription Process

- Chapter 3: Ribosome Recognition and Translation of Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Messenger RNA

- Chapter 4: Gene Order

- Chapter 5: RNA Replication

- Chapter 6: Rhabdoviral Assembly and Intracellular Processing of Viral Components

- Chapter 7: Rhabdovirus Genetics

- Chapter 8: Gene Assignment and Complementation Group

- Chapter 9: Homologous Interference by Defective Virus Particles

- Chapter 10: RNQ Synthesis by Defective Interferring Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Particles

- Chapter 11: Rhabdovirus Defective Particles: Origin and Genome Assignments

- Chapter 12: Interference Induced by Defective Interferring Particles

- Index