![]()

![]()

1

SAMARKAND GAINED AND LOST

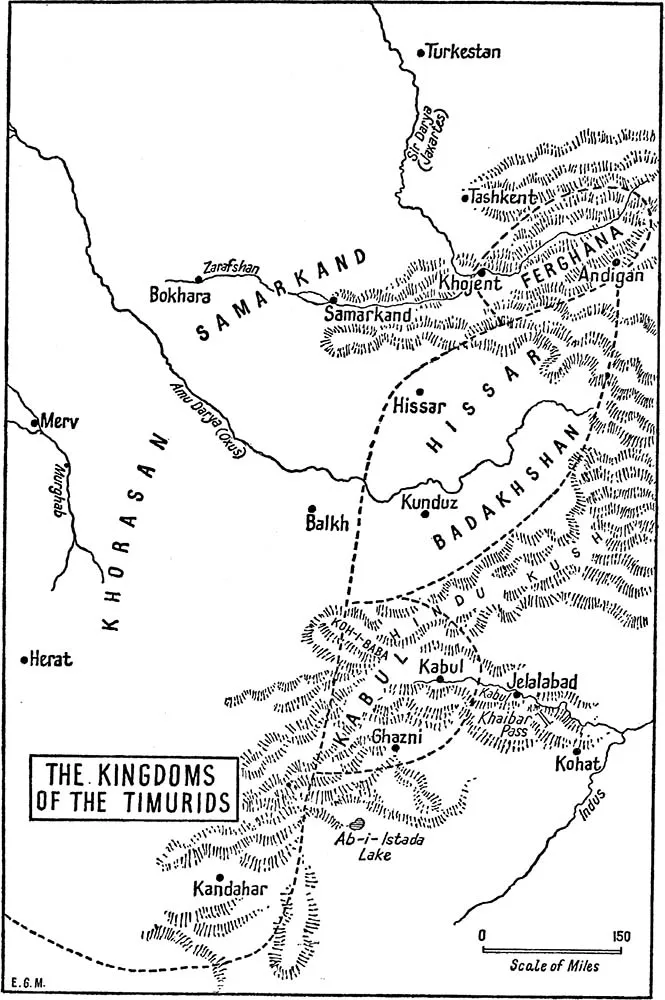

OVER two and a half centuries had passed since Jenghiz Khan, out of the vastness of East Asia, had irrupted into the lands of the Sir Darya and Amu Darya and smashed the Moslem Empire then stretching from the Pamir to beyond the Caspian Sea. Forty years later the Mongols, under Jenghiz Khan’s grandson Hulagu, had subjugated all the realms to the west of the Oxus, nearly as far as the Mediterranean, and were only stopped by the Egyptian Mamelukes from conquering the whole of Syria. Then, in the space of a few generations, the Empire of the Il-Khans, which Hulagu had founded, changed its character, as had happened so often in the history of western Asia, where the settled world of Persian civilization had absorbed wave after wave of invaders from the steppes. Hulagu’s descendants, and more and more of the Mongolian nobles, went over to Islam; the nomad rulers surrounded themselves with scholars and poets, building palaces and towns to their glory, and spending their time in festivities or wars against one another. Real power was wielded by the viceroys and amirs in the various provinces. As soon as one of them felt strong enough, he discovered some descendant of Jenghiz Khan, proclaimed him Khan, and in his name started wars against his neighbours in the hope of annexing their provinces.

It was about a century after the creation of Hulagu’s Empire that in the region of the Amu Darya (the Oxus) and the Sir Darya (the Jaxartes of old) a new power arose. This region, Jenghiz Khan’s original target, did not really belong to Hulagu’s Empire. The land beyond the Amu Darya had been allocated to the realm of Jagatai, Jenghiz Khan’s second son, whose central Asian empire was intended to form a bridge between China and Western Asia. But the eastern half of Jagatai’s realm, Turkistan, poor in cities and rich in steppes, remained a typical nomad land, while its western part, Transoxiana, between the Amu Darya and Sir Darya, was populous, industrious, and culturally and economically much more akin to the empire of the Il-Khans which bordered it to the south-west.

In this frontier land between Iran and Turan a chieftain of the Barlas Turki-tribe, Timur, had himself proclaimed Grand Amir of Transoxiana in the year 1369, and with a Jenghizid as nominal Khan started on the superhuman task which he had set himself: that of re-establishing Jenghiz Khan’s empire. When he died thirty-six years later, he left what is known in Europe as Tamerlane’s Empire, reaching from the Aral Sea to the Arabian Sea and from the Mediterranean nearly to the Altai Mountains. But he had not, like Jenghiz Khan, created a warrior nation, since he made his conquests with an army of mercenaries held together in the main by his personality and the expectation of spoils. And in spite of the frightful destruction which accompanied his campaigns, it was the Iranian-Islamic civilization which not only survived but re-emerged from the slaughter strengthened and enhanced.

Timur’s descendants felt themselves heirs more to a culture which they wanted to enjoy and foster than to the ambition of world conquest. Fighting one another for the throne, for a province, for a fief they often sought help from the nomadic warriors of Turkistan or of the northern steppes against their immediate neighbours, only to discard their helpers at the moment of success in order to pursue a life of culture and pleasure as the previous rulers had done. Proud of their learning and their manners, they considered themselves not Mongols but Turks, superior to the rough Mongolian riders of the steppes. And the nomads, whether they came from outside the province or were wandering with their cattle in its hills or wastes, felt themselves in no way bound to the man by whom they had been engaged for a campaign. When the fortunes of battle turned against him, they simply plundered his camp before fleeing themselves.

This struggle for the succession started immediately after Timur’s death. Nevertheless, when after four years of strife his youngest son Shah Rokh established his supremacy, he managed to bring back a great part of the empire under his rule and to leave the throne, after a prosperous reign of nearly forty years, to his son Ulugh Beg, a great scholar, poet, theologian, and eminent mathematician, whose astronomical tables became world-famous. Yet, after a short reign Ulugh Beg was dethroned, and then murdered, by one of his sons. A fratricidal war plunged the country again into chaos, until a great-grandson of Timur from another line, Abu Said, established himself on the throne of Samarkand with the help of the Uzbegs, the nomad Mongols from the northern steppes.

An able ruler and a keen warrior, Abu Said kept order in his realm, but before engaging on a campaign against Irak, where he was defeated and killed, he divided it amongst his sons. The lands of Samarkand and Bokhara he apportioned to his eldest son Sultan Ahmed, the Amu Darya basin with Hissar and Badakhshan to his son Sultan Mahmud; another son, Omar Sheikh, inherited the kingdom of Ferghana, lying eastwards on both sides of the upper Sir Darya; and still another son, Ulugh Beg, held the far-off mountainous kingdom of Kabul. The rich kingdom of Khorasan to the south and west of these realms, stretching from Afghanistan to the Amu Darya, was conquered by another great-grandson of Timur, Sultan Husain Baikara, who, an admirer of art and literature, made his capital Herat one of the greatest cultural centres of the Asian Mohammedan world.

The little kingdom of Ferghana, Omar Sheikh’s domain, was, as Babur later wrote in his memoirs, ‘situated on the extreme boundary of the habitable world’. It was surrounded on three sides by mountains and open only to the west, towards Samarkand. Beyond it, on the other side of the mountain passes, was the land of the Jagatai Mongols, but their Khan, Yunus, a descendant of Jenghiz Khan, had spent his youth as an exile at the courts of descendants of Shah Rokh and loved town life. Three of his daughters had married sons of Abu Said, and with one of them, his son-in-law Omar Sheikh, the King of Ferghana, he struck up a particular friendship and often spent the winter months in his kingdom. When Omar Sheikh’s wife, early in 1483, gave birth to a boy and he was named Zahir-ud-din Mohammed—Defender of the Faith—it is said that the Mongols, finding the name difficult to pronounce, called him Babur—Panther; and it was under this soon generally adopted name that the boy, the descendant of both Timur and Jenghiz Khan, made his entrance into history.

Ferghana was, as he described it, a beautiful country ‘abundantly supplied with running water and extremely pleasant in spring’. Its orchards and gardens were celebrated, full of tulips and roses. It abounded in corn and fruits, particularly peaches, apricots, melons, and pomegranates. The people liked to take the stones out of the apricots and insert almonds in their place, (which is very pleasant). It had a rich soil and sheltered meadows of clover. It had good hunting grounds with plenty of game. ‘Its pheasants were so fat that four persons could dine on one and not finish it’. In the hills there were delightful summer retreats to which the people retired to avoid the heat. There were ‘mines of turquoise, and the people in the valley wove cloth of purple colour’. But the country was small and its revenue just sufficient to maintain 4,000 troops. Omar Sheikh, ambitious and adventurous, often set out for inroads into the neighbouring domain of Samarkand, and sometimes it needed the mediation of Yunus Khan and the menace of his Mongols to prevent Sultan Ahmed, the lord of Samarkand, from overrunning the kingdom of his unruly brother. However, when after the death of Yunus Khan the adventurous Omar Sheikh did not stop his pillaging invasions, Sultan Ahmed and his brother-in-law, Mahmud Khan of Tashkent, the elder son of Yunus Khan, decided to divide Ferghana between themselves and marched in the spring of 1494 from west and north into the country. Omar Sheikh was at the time in the mountain fort of Akhsi, where his palace buildings were erected at the edge of a precipice, and while he was, perhaps on the look-out for the invaders, feeding his pigeons, the platform with the dovecote gave way under him and he was hurled to his death from the top of the rock.

When the news of the accident reached the capital, Andijan, his eleven-year-old son Babur was immediately proclaimed king, and the begs and amirs, knowing how precarious the position was and what pillage and murder usually accompanied the fall of a city, prepared for defence. In the meantime an embassy went in Babur’s name to his uncle Sultan Ahmed, stating that he regarded himself as son and servant of the Sultan and would be happy to govern the country as the Sultan’s regent. But the Sultan’s ministers rejected the proposal and the army continued to advance. However, while it was crossing a muddy and slimy river the only bridge collapsed, many horses and camels fell into the swamp and perished. Then an epidemic of distemper broke out among the animals, and Sultan Ahmed called off the campaign. On the way back he himself was seized with fever and died. Babur’s maternal uncle, Mahmud Khan, who was besieging the fortress of Akhsi, fell ill, too, and returned to his country. Babur notes in his memoirs: ‘The Almighty God, by His perfect power, has in His own good time and season accomplished my designs in the best and most proper manner without the aid of mortal strength’; and it was probably in the desire to prove himself worthy of this divine mercy that the boy ‘began to abstain from forbidden and dubious meats’ and even refrained from alcohol —a most astonishing feat in his surroundings.

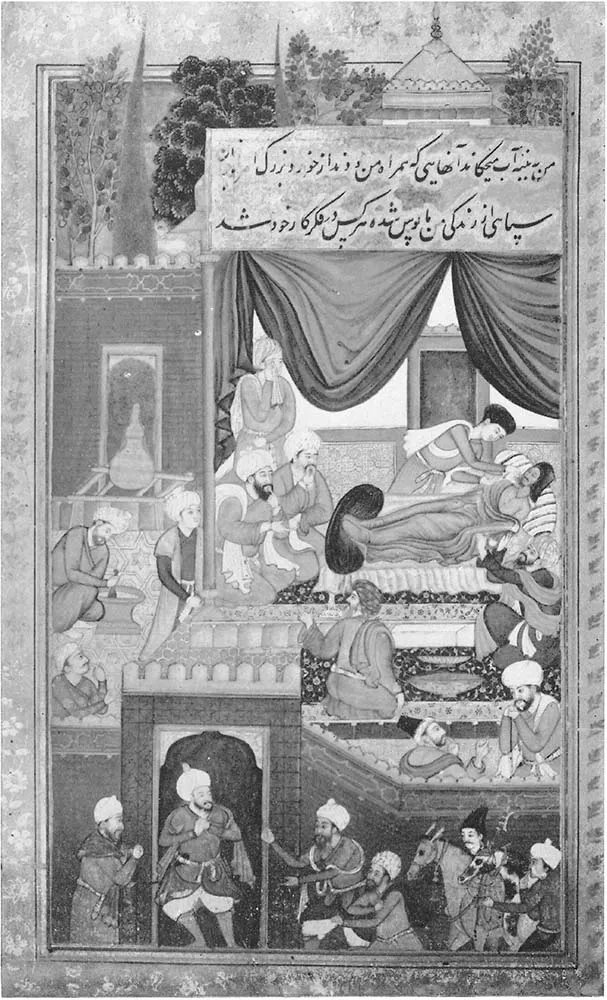

1. Young Babur dangerously ill in Samarkand. A physician sprinkling his face with water.

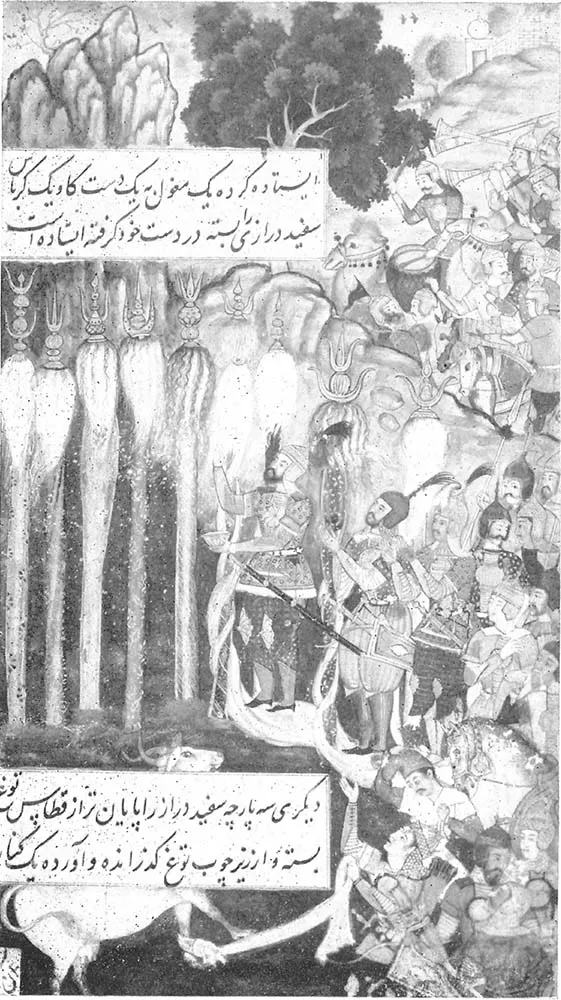

2. Babur and his uncle’s armies saluting the Mongolian horse-tail standards by throwing Kumiss on them.

After Ahmed’s death, his brother, Sultan Mahmud, mounted the throne of Samarkand, but being tyrannical and debauched he soon earned the hatred of the people of the capital. During the twenty-five years of Ahmed’s reign they had lived in ease and tranquillity, now they feared to leave their houses ‘from a dread lest their children be carried off for slaves’. However, after a few months Sultan Mahmud also fell ill and died within six days.

Now the begs of Samarkand called in Baisanghar, the eighteen-year-old son of Sultan Mahmud, but other Mirzas—as all princes of Timur’s stock were called—also raised their claim to the throne of Samarkand and, accompanied by their begs and retainers, began incessant warfare. In reality they were only puppets in the hands of their begs, who eager for spoil and power readily changed one Mirza for another or even blinded or assassinated an uncomfortable one if he did not manage to escape in time to a domain or town in the power of another war-lord.

Babur’s begs of Ferghana had used the general commotion, first to regain some towns and forts which had been lost after Omar Sheikh’s death; then they set out, with the now thirteen-year-old Babur, towards Samarkand. However, the armies of the various pretenders had finally exhausted the resources of the country, ‘great scarcity of provisions prevailed everywhere and as the winter season was fast approaching’ the campaign was postponed to the next year.

When in 1497 Babur’s army advanced again in the direction of Samarkand, it proved to be somewhat better disciplined and behaved than the others, and various towns and forts surrendered and were spared. A number of nomad bands joined him, and when these Mongols plundered a few peaceful villages, the leading beg ‘ordered two or three of them to be cut to pieces as an example’. The result was that when Babur encamped before Samarkand ‘so many townspeople and traders arrived that the camp was like a city and one could buy there whatever was procurable in the town’. One day the soldiers could not resist the temptation and raided the stalls, but on the order ‘that everything should be restored without reserve before the end of the first watch next day, there was not a thread or a broken needle that was not restored to its owner’, writes Babur.

Nevertheless, the siege lasted seven months, deep into the winter, before Baisanghar, ‘with two or three hundred hungry and naked wretches’, fled from the city and Babur was welcomed by the begs and chief townsmen of Samarkand. The capital of his great ancestor Timur made an overwhelming impression on the fourteen-year-old boy and it exercised a fascination on him which was to last throughout his whole life, making him ready more than once to sacrifice all he had won for a chance to regain possession of this city. Its palaces, its mosques, its gardens, its baths, its halls, its colleges, everything was incomparably magnificent. ‘In the whole inhabitable world there are few cities so pleasantly situated as Samarkand … I directed its wall to be paced round the ramparts, and found that it was five miles in circumference.’

In his description of Samarkand he does not forget the observatory, by means of which ‘Ulugh Beg composed the Astronomical Tables which are followed at the present time, scarcely any other being used. Before they were published, the Il-Khani Astronomical Tables were in general use, constructed in the time of Hulagu, in his observatory …

‘Samarkand is a wonderfully fine city. One of its distinguishing peculiarities is that each trade has its own bazaar; so that different trades are not mixed together in the same place. The established customs and regulations are good. The bakers’ shops are excellent, and the cooks are skilful. The best paper in the world comes from Samarkand … Another product of Samarkand is crimson velvet, which is exported to all quarters …’

But the town had been taken after severe resistance. It had been pillaged according to custom, and as it soon proved so completely, that instead of being taxed the inhabitants had to be given ‘seed-corn and supplies to enable them to carry on till the harvest’. The soldiers had acquired considerable booty when the city fell, but now they could only expect hardship. There were no riches left to plunder, Babur had nothing to give them, and so they began to desert him. First the Mongol tribes went away, then the troops from Ferghana, with even the most important begs, returned home, and then the news arrived that these begs, considering Babur now to be the lord of Samarkand, had proclaimed his younger brother Jahangir as King of Ferghana. It was quite customary that each son of a ruler should receive a separate appanage, but as Babur’s whole strength derived from Ferghana his governors refused to surrender the capital Andijan, and the rebels laid siege to the city.

Urgent letters from Babur’s mother called on him to hasten with his remaining troops to the relief of his old capital, but just at this moment the boy fell so seriously ill that he could neither speak nor take nourishment, and even the men who had loyally remained with him despaired of his life. However, he recovered and a hundred days after his entry into Samarkand he left the city with his little army to hurry to Ferghana. But when after a week he reached Khojent, less than half way to his capital Andijan, news came that, in the belief that he was dying, the garrison of Andijan had made terms with the enemy and surrendered the fortress, while immediately on his departure from Samarkand his cousin Ali Mirza had occupied the city. Babur had lost both his kingdoms, his own Ferghana and his beloved Samarkand. Now the begs, captains and soldiers who had wives and families in Andijan, about seven to eight hundred men, left him altogether. Not more than two to three hundred followers of all ranks stuck to him, ‘voluntarily choosing a life of exile and hardship’. To make matters worse, Khojent was such a small place that it could not maintain even two hundred men, and Babur confesses that he became ‘a prey to melancholy and vexation, and wept a great deal’.

Then his grandmother and mother arrived from Andijan. As the widow and the daughter of Yunus Khan, they had many connections. One of his mother’s brothers, Mahmud Khan of Tashkent, gave Babur a detachment of Mongols; a number of Babur’s officers and begs were sent out into the hills to gain the help of the mountain tribes; and slowly, as the news spread that Babur was gathering forces to fight for his heritage, the country, discontented with the arbitrary rule of the new masters, became restive. One after the other, forts and towns drove out the imposed governors and opened the gates to Babur’s envoys. Various engagements ended in his favour, and finally Andijan declared itself for him: ‘Thus by the grace of the Most High I recovered my paternal kingdom, of which I had been deprived for nearly two years’.

But fortunes changed quickly. A great part of his forces consisted of mercenary Mongol tribes who had first joined his adversaries and lately, seeing his success, changed over to his side, each time using the opportuniy to plunder the losers. Now Babur’s retainers came to him complaining that the Mongols ‘are riding the horses which were ours, wearing our garments, and killing and eating our own sheep before our eyes. What patience can possibly endure all this?’ Babur found that their complaints were just and allowed them to ‘resume possession of whatever part of their property they recognized’.

The Mongols were not the men to give back any of their spoils. There were about three to four thousand of them, and they immediat...