eBook - ePub

Locating Health

Sociological and Historical Explorations

- 270 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Locating Health

Sociological and Historical Explorations

About this book

Originally presented as papers in the 1991 British Sociological Association Conference on Health and Society, Locating Health represents a valuable addition to the 'health inequalities' debate by extending our gaze beyond the traditional locations to include place, consumption and lifestyle. It offers reconceptualization of key theoretical terms, including work, income, and public/private domains as well as addressing the reciprocal influence of health and social location, for example early retirement; and highlighting the health consequences of multiple locations, such as gender and class, gender and age.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Locating Health by Stephen Platt,Hilary Thomas,Sue Scott,Gareth Williams in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

Stephen Platt and Hilary Thomas

Health divisions and inequalities have been long-standing topics of empirical investigation and interpretation among sociologists, epidemiologists and those charged with promoting and maintaining the public health. During the last decade alone several books and edited collections, as well as countless articles in academic journals, have been devoted to describing, measuring and explaining variations in morbidity and mortality by class and economic activity. Nevertheless, a number of lacunae or weak spots in the health inequalities debate can still be identified. These include the relative neglect of divisions associated with other key social locations, such as gender, age and race/ethnicity, and the overemphasis on mortality, which is increasingly recognized as a poor indicator of morbidity and an even less adequate guide to positive health. Furthermore, there has been a failure to devise and execute sound empirical tests of competing explanations for the (widening) health inequalities which are uncovered; and an increasing disjunction between advances in statistical techniques and methodological sophistication, on the one hand, and underdeveloped conceptual and theoretical frameworks, on the other.

The chapters in this collection are revised versions of papers originally presented at the British Sociological Association’s 1991 conference, entitled ‘Health and Society’. The balance of the collection attempts to shift the existing debate towards a consideration of some of the complexities of health inequalities research by addressing issues of morbidity rather than mortality, emphasizing the theoretical and conceptual bases of the subject and developing new methodological approaches in the examination of data. Four major concerns can be identified throughout the collection: the reconceptualization of key theoretical terms; the health consequences of multiple social locations; the reciprocal relationships between different locations; and the importance of newly identified social locations. Much of the discussion about inequalities in health has taken occupational social class as a framework for the social differentiation of circumstances and resources within the population. Within this collection the importance of income differentials is subjected to detailed scrutiny. Likewise, the boundaries of paid employment are assessed in relation to both domestic labour and retirement. The direct implications of paid employment for the health of workers are considered. The need to clarify similar constructs within different social structures is highlighted by an analysis of gender and health in Eastern and Western Europe. Early retirement provides a salient focus for an examination of the reciprocal influence of health and social location. The complexity of understanding multiple location within social structure is addressed in chapters combining gender and class, and gender and age. Newly emergent locations include place, consumption and ‘lifestyle’.

Richard Wilkinson draws attention to the highly significant correlation between income distribution and average life expectancy in the developed countries and, having dismissed the likelihood of reverse causation or spurious association, concludes that ‘relative income does indeed affect health’. On the basis of further empirical analysis he concludes that it is the social meanings of structural inequality (‘how we stand in relation to each other’), rather than the physical effects of poverty (‘where we stand in terms of any absolute standards’), which may now have a significant impact upon our physical and emotional well-being. Although the pathway between income distribution and death is as yet little understood, Wilkinson suggests that we need to explore further the role of psychosocial risk factors, in particular reduced or inadequate social affiliations (poor social support, lack of confiding relationship), which in turn may be linked to behavioural risk factors, such as smoking or alcohol/drug abuse.

Sara Arber and Jay Ginn analyse the ways in which three types of resources - the health and physical abilities of the individual and other household members; material or structural resources, such as income and housing; and access to personal, supportive and health care - interlock to form a ‘resource triangle’ which influences independence, well-being and personal space among people aged 65 years and over. Their chapter examines the inter-relationships between these three sets of resources and demonstrates how the resource triangle is gendered, with older women being systematically disadvantaged in each of the three key resources compared to older men. However, the authors also note that gender differences in self-assessed health in later life appear to be less important than differences associated with class. They comment that the finding of strong class gradients:

may be surprising, given that for elderly people occupational class is based on their labour market position many years earlier, especially for women of this generation who may not have worked since marriage.

Overall they conclude that the resource triangle is affected by both gender and class: elderly women and working-class elderly people suffer the most unfavourable conditions in each kind of resource. The inequalities caused during the economically active years by disadvantageous locations in the productive and reproductive systems form part of the burden that is carried into old age.

Sally Macintyre compares Western European (and North American) data on gender differences in longevity and health with new data now emerging from Eastern European countries. Life expectancy at one year of age is about four years higher in the West, and the difference in longevity between men and women is greater in the East. Between the mid-1960s and the mid-1980s, when life expectancy was increasing in Western Europe, there was actually a decline in life expectancy in a number of east European countries (USSR, Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Poland). Macintyre laments the artificial separation between the literature on health inequalities and the literature on gender differences in health. The latter reveals the well-known paradox that, while women are more likely to suffer from illness and disability, and to use more health care resources, men die at a younger age. Noting that the body of knowledge concerning gender differences in illness and disability mainly originates in empirical studies conducted in North America and Western Europe, Macintyre speculates whether the current explanations based on the expectation of gendersegregated roles are likely to be as applicable to the situation in Eastern Europe. She concludes with a plea for the incorporation of gender differentials in morbidity and mortality into research and thinking about social inequalities in health.

An historical perspective to debates about women’s employment and the relationship to domestic labour is provided by Barbara Harrison. She seeks to explore the health consequences of women’s working conditions in late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century Britain, in particular the significance of occupational health as a issue within feminist analysis and politics. By the 1840s state intervention in the industrial system (by means of ‘protective’ legislation) included women as well as children in its purview. Harrison demonstrates that the protection of women as a special group arose out of concerns about their continuing ability to care for their husbands and children (domestic role) as well as worries about their perceived physical vulnerability. The intention of factory legislation, however, was not necessarily to protect the health of women qua workers, but to protect the health of the nation from the dangers of working women by preserving separate gendered domains of responsibility and women’s duty to preserve the health of others within their domestic role.

Jennie Popay and Mel Bartley develop an integrated theory of the relationships between labour conditions, gender and social class inequalities in health. Using a proportional odds modelling technique and data from two national datasets, they explore the relative importance of domestic working conditions in shaping the experience of ill-health among women in paid employment. After controlling for the effect of long-term health status, new measures of domestic conditions and physical and psychosocial conditions of formal paid work (employment) were associated with a significant increase in the risk of experiencing severe recent illness among women. Among men, however, no such effects were found. More importantly, perhaps, conventional measures of working conditions - namely, class and employment status - failed to make a significant independent contribution to the models. Although the authors rightly voice their concern about the validity of the short-term health measures used in the analysis, we endorse their claims for the theoretical significance of unified measures of labour demands and conditions.

Whereas early retirement used to be connected almost exclusively to deteriorating health, recent commentators have suggested that economic/ financial factors may now be more salient. Based on a review of the evidence from three recent studies of male early retirement, Dallas Cliff argues that, while the majority of early retirees have responded to favourably perceived economic incentives, a substantial minority of men, mainly manual workers, are replicating earlier patterns by taking early retirement due to a breakdown in health:

[W]hile most early retirees go on to negotiate varied careers which mix family and leisure pursuits, short-term and part-time employment and voluntary work in ways that are generally highly satisfying, others, mainly manual workers, experience early retirement in terms of ill-health careers that cut down their options and leave them financially and socially impoverished.

Cliff finds empirical support for the contention that the divide between ‘lifestyle-orientated’ (mainly middle class) retirees and those who are reproducing earlier patterns of health-related early retirement (mainly working class) is widening.

In an historical case study Andrew Watterson looks at the introduction of new technologies into the gas industry in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the occupational health hazards created by such developments, and the responses of workers and other key groups. He concludes that, although gas workers tried to combat the prevailing ignorance about occupational ill-health in the industry, they were:

neither able to alter the dominant established social processes for defining occupational diseases nor overcome the political economy of the time which created particular gas industry health hazards.... Occupational medicine lost the struggle to political economy at an early date.

In his chapter Peter Phillimore seeks to wean the debate about inequalities in health away from its excessive reliance on simple statistical measures and the epidemiological paradigm, towards a broader sociological understanding of the social creation of health differences. He starts with evidence of excessive mortality in the poorer and predominantly workingclass areas of Middlesbrough compared to that found in similarly constituted areas of neighbouring Sunderland. Based on the proposition that, whatever the broad socio-economic similarities between the two populations, ‘there must also be striking differences in the lives people lead in these towns to have produced such dissimilar mortality patterns’, Phillimore sets out to examine three sociological themes that may be relevant to an understanding of such differences: the industrial environment, polarization and social inequality within each town, and ‘the ways in which people themselves shape their environment in the two towns’. When, in the context of this third theme, Phillimore refers to ‘lifestyle’, he does not have in mind disparate individualized behaviours such as smoking or drinking, but rather ‘fears, values and habits’, the conceptualization of ‘daily routines, decision-making and choice against a background of a struggle to survive’.

In his contribution to the debate about the costs and benefits of the industrial revolution to the well-being of the British population, Rory Williams examines the regional health experience of historical and contemporary Clydeside and presents an initial assessment of the role of immigration from the Scottish Highlands and from Ireland in Clydeside’s industrialization. Whereas in England falling prices after the Napoleonic War tended to lead to a rise in real wages, the reverse was true in Clydeside. Moreover, although Glasgow’s death rate was only slightly higher than the English national figure in 1821, the ensuing rise in industrial output and surge of immigration was accompanied by a rapidly escalating death rate which did not fall back to the 1821 level until over 60 years later; over the same period the death rate in England remained fairly steady. Williams argues that the growth of industrialism coincided with the collapse of peasant populations, and that the mortality profile of Glasgow and Clydeside was related to ‘patterns of urban poverty brought about by the migration and factors antecedent and subsequent to it’.

Michael Calnan, Sarah Cant and Jonathan Gabe draw on recently collected data on private health insurance in order to examine the theories of consumption in relation to health care. In particular, they ask whether the development of private health insurance signifies ‘new’ social divisions (in distinction to traditional divisions, such as social class, relating to the sphere of production). On the basis of qualitative interviews with 60 middle-aged men (of whom 20 had chosen to take out private health insurance, 20 had been co-opted into employer-run schemes, and 20 who had not subscribed to a scheme), the authors conclude that:

consumption of private health insurance has little power to explain or account for the ‘new’ social divisions.... [T]he evidence from this study adds weight to the claims of those who have argued that private medical care challenges the proposition that divisions of consumption have replaced divisions of production.

In the final chapter David Smith and Malcolm Nicolson consider twentieth-century discourse about the diet of the working class and show that recent allegations of ignorance constitute merely another example of a moralizing rhetoric used repeatedly by scientists and politicians. They argue that the association of ignorance with ill-health is:

both a structured ideological response to the social threats and dangers posed by class inequality and a feature of the general pattern of control and discipline imposed upon the body in an advanced industrial society.

The chapters in Locating Health are intended to make a stimulating intellectual contribution to the debate on health-related divisions and inequalities which is likely to continue unabated during the 1990s. While the issues covered in this book are undoubtedly of interest to academics teaching or researching in the sociology of health and illness, it is hoped that policy planners will find the collection of practical relevance in the implementation of recent health care reforms, especially the identification of health needs within special population subgroups.

2 The impact of income inequality on life expectancy

Richard G. Wilkinson

Introduction

When I first got involved in research on ‘inequalities’ - or social class differences - in health, I was sensitive to the charge that the issue was really only of interest to those who were more concerned with inequality than with health itself. The standard defence against the charge was, however, that health inequalities provided an important aetiological clue to the determinants of health. At least they served as an important reminder of the continued sensitivity of health to socio-economic factors. With what I thought at the time was a little wishful thinking I, like others, suggested that socio-economic differences in health might lead us to factors which had a crucial influence on the health of the whole population. I now feel rather taken aback to find that this is exactly what has happened. The results of a series of research projects - made possible by funding from the Economic and Social Research Council - suggest that the degree of socioeconomic inequality in developed societies is a key determinant of the average standard of health of their populations. Figures 1 and 2 show clearly that, among the rich developed countries, it is not the richest countries which have the highest life expectancy, but the ones with the most egalitarian distribution of income.

As inequality has always been one of the central concerns of sociology these relationships place the determinants of health firmly in the sociological court. I would first like to go through the evidence which makes me think that the relationship between average life expectancy and income inequality is causal, and then go on to discuss some of the mechanisms which may be involved.

Income distribution and health: national and international evidence

The relationship between income distribution and health is quite robust. It has now been demonstrated several times on cross-sectional evidence, using different measures of income distribution, from different countries, at different dates (Rodgers 1979; Wilkinson 1986a and 1990; Le Grand 1987). More recently it has been shown that there is also a relationship between changes (over periods of five to ten years) in income distribution and in life expectancy in developed countries (Wilkinson 1992). As well as being robust, it is, in statistical terms, a strong relationship. Despite the small number of observations, the correlation coefficients are usually highly significant and suggest that as much as two-thirds of the variation in life expectancy between these countries may be related to the differences in their income distributions.

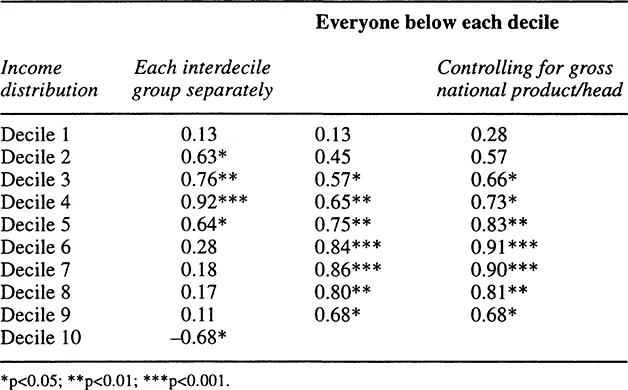

Table 1 Pearson correlation coefficients for relation between life expectancy (male and female at birth) and income distribution in nine countries in the OECD

The best source of internationally comparable income distribution data comes from the Luxembourg Income Study. Table 1 is based on its figures for Australia, Canada, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, (West) Germany, UK and USA in 1981 as published by Bishop et al. (1989). It shows the correlation coefficients between life expectancy at birth of males and females an...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Impact of Income Inequality on Life Expectancy

- 3 The Gendered Resource Triangle: Health and Resources in Later Life

- 4 Gender Differences in Longevity and Health in Eastern and Western Europe

- 5 Feminism and the Health Consequences of Women’s Work in Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century Britain

- 6 Conditions of Formal and Domestic Labour: Toward an Integrated Framework for the Analysis of Gender and Social Class Inequalities in Health

- 7 Health Issues in Male Early Retirement

- 8 Occupational Health in the UK Gas Industry: A study of Employer, Medical and Worker Knowledge and Action on Occupational Health in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century

- 9 How do Places Shape Health? Rethinking Locality and Lifestyle in North-East England

- 10 The Health Costs of Britain’s Industrialization: A Perspective from the Celtic Periphery

- 11 ‘Keeping up with the Joneses?’ Private Health Insurance as a Consumption Good?

- 12 Health and Ignorance: Past and Present

- Index