- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

When originally published in 1979, this was the first comprehensive study of the Jakhanke in any language. Despite the 19th ambience of jihad, the Jakhanke maintined their tradition of consistent pacifism and political neutrality which is unique in Muslim Black Africa. Drawing on histories, interviews, and colonial reports the book traces the details of the Jakhanke pilgrimages and analyses important themes such as their system of education, their function as dream-interpreters and amulet-makers and finally the dependence of their way of life on the institution of slavery.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Jakhanke by Lamin O. Sanneh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

THE BIRTH OF THE JAKHANKE ISLAMIC CLERICAL TRADITION

c. 1200 – c. 1500

Introduction

A familiar but intractable problem in African history is the question of the identification and origin of nomenclature and ethno-linguistic groups, and the Jakhanke people are no exception. They have been ascribed various names (see p. 27) and even now some confusion remains about how to resolve the problem. Among the Jakhanke themselves the Arabic form ahl Diakha (or Dia) is used. The phrase means ‘the people of Diakha’, and refers to the ancient Sudanic town in Masina visited by Ibn Baṭṭūṭa. The Jakhanke are by origin the same people as the Sera-khulle, sometimes also known as Soninke,1 and are distinguished only by a professional specialisation as Muslim clerics. The appellation ‘Jakhanke’ merely describes their original geographical home, Diakha-Masina, and does not relate to any theory of ethnic origins. Jakhanke sources indeed use the Arabic word nawc, kind, branch, to describe themselves, rather than jins, race or species. An historian need not, therefore, be overly exercised about the question of ethnic origins in order to identify and describe the community ahl Diakha. That is our approach in this book. It is important to stress this lest an erroneous impression be created that the Jakhanke are a distinct ethno-linguistic grouping with a language of their own. Charlotte Quinn rather hastily describes the Jakhanke as a Mandinka people ‘from Futa Tuba [Touba] who spoke a dialect of Mandingo different from their neighbours in the Gambian states’ (1972: 172). Jakhanke clerics have until recent times conducted Qur’ānic exegesis (tafsīr) in the Sera-khulle language, while using relevant languages, such as Susu, Fula, and Wolof in everyday contact with the people living around them. Indeed such ethnic distinctiveness as they may have acquired is usually the result of historical intermixture with adjacent peoples and not of an original linguistic affinity.

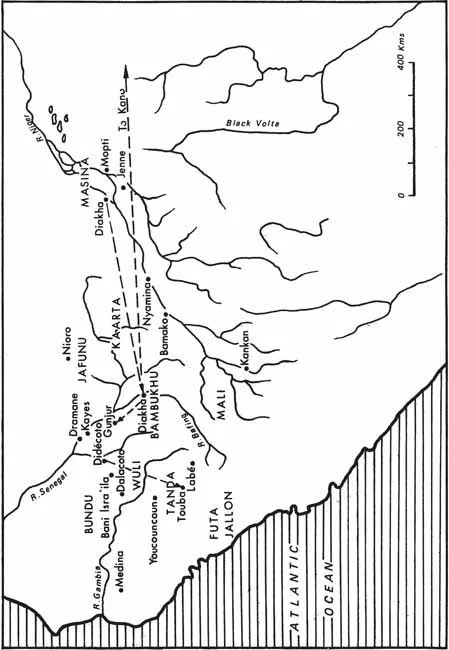

The community of ahl Diakha acquired a separate identity by virtue of an occupational clerical tradition on the one hand, and, on the other, of a common acknowledgement of al-Ḥājj Sālim Suware as the originator of their way of life. At a very early date the Jakhanke were characterised by large-scale dispersion (Ar. tafrīq) and this accounts in part for the different names by which they are known. Dispersion, as shown in the Introduction, is a grand theme in Jakhanke history, and to this may be added other factors of geographical mobility, such as educational travel, tournées pastorales and other special purpose visits such as pilgrimage (Ar. ḥājj). What the cleric practises as he moves from place to place, that is, the thematic content of clerical activity, is described in detail in later chapters. For all this the figure of al-Ḥājj Sālim Suware is predominant. As the source and proto-type of Jakhanke clericalism his stature is without parallel and a history of the Jakhanke as ahl Diakha must start with him.

Surprisingly little is known of the life and work of al-Ḥājj Sālim, and even hagiographical material is hard to come by. This, no doubt, is connected with the Jakhanke aversion to anything that might appear as blameworthy or heretical (Ar. bidcah).2 One or two recent studies have tried to establish the person of al-Ḥājj Sālim but did not get beyond a few intuitive conclusions (P. Smith 1965a; Wilks 1968). That al-Ḥājj Sālim was an historical figure is indubitable, and beyond that his influence is felt in all Jakhanke communities to such an extent that he must have been an exceptional leader in his time. We must now turn our attention to him, drawing principally on local Jakhanke Arabic sources for an outline of his life and career.

Al-Ḥājj Sālim Suware and the Origins of Jakhanke Clericalism

Sometimes called Mbemba Laye Suware,3 al-Ḥājj Sālim arrived in Diakha-Masina, on the Niger buckle, after his legendary seventh and last pilgrimage to Mecca. It was on his return journey that the nickname (Ar. laqab), ‘Su-ware’, meaning a piebald horse, was applied to him by his admiring entourage.4 He had not intended to return to Black Africa from Mecca, but a dream he had there urged him to return and undertake missionary work. Thus opened a chapter in his life which was to leave a permanent imprint on West African Islam.

Traditional accounts make al-Ḥājj Sālim a contemporary (but more plausibly a man of equal stature) of Magham Diabe Sise, the founder-king of Wagadu, that is, the ancient Ghana of written sources.5 Although some accounts place some emphasis on this contemporaneity, they should not be pressed for their chronological value only. What they might be saying is that if Magham Diabe Sise can be seen as representing a secular/political impulse in Serakhulle history, so can al-Ḥājj Sālim be seen as representing a contrasting and independent religious/clerical line. Magham Diabe and al-Ḥājj Sālim are thus two stylistic representations in oral tradition of a differentiation between political innovation leading in one direction, and in another an autonomous clerical establishment in Serakhulle history. The Jakhanke, arguing their own case rather than the secular triumph of Magham Diabe, ascribe to al-Ḥājj Sālim an importance which, although clearly exaggerated, is not altogether undeserved.

In an Arabic document obtained on the field in Senegambia and to be referred to hereafter as TSK,6 an account is given of how al-Ḥājj Sālim and his large entourage left Diakha-Masina following unspecified political upheavals in that region. Al-Ḥājj Sālim decided to leave because of what the sources describe as a fundamental aversion to assuming secular responsibility or being involved in war, thus introducing the two important themes of Jakhanke history: dispersion, in this instance because of war, and withdrawal from politics and armed conflict.

When al-Ḥājj Sālim left Diakha-Masina to settle first in Jafunu and then in Diakha-Bambukhu, he was accompanied by numerous followers: students, members of his family, qabīlah communities (clan segments), and other sympathisers and disciples. Charles Monteil mentions the names of only three of al-Ḥājj Sālim’s disciples: Salla Kebe, Baba Kamara, also called Wage and ancestor of the Kamara-Wage of Kagoro, and Fa Abdullahi Marega, whose descendants dispersed to Mulline, near present Kunyakari (Ch. Monteil 1953: 372; on the Marega in Kayes see Brun 1910). TSK gives fuller details, and when the list it supplies is conflated with similar information given by al-Ḥājj Soriba Jabi, a Jakhanke scholar of Senegal and the younger brother of al-Ḥājj Banfa Jabi, we have an impressive list of al-Ḥājj Sālim’s leading ṭullāb (sing. tālib) (students). TSK coincides exactly with al-Ḥājj Soriba with regard to the patronymics represented in al-Ḥājj Sālim’s entourage. Both he and TSK also stress the Serakhulle composition of al-Ḥājj Sālim’s community. Except possibly for the names Kamara and Jawara (Diawara), all can be identified as essentially Serakhulle: Sakho, Karara, Maigha, Fadiga, Kabba, Fofana-Girasi, Darame, Silla, Gassama and Kayasi (TSK: fos. 1 and 2; Sanneh 1974a: 93–4). But al-Ḥājj Soriba’s list is slightly longer than TSK. The Serakhulle theme is pursued further in the sources. TSK says two members of al-Ḥājj Sālim’s family, probably his sons, were uterine brothers (Ar. shaqī-qāt), namely, Darameba and Kharu Muḥammad Fofana-Girasi, and that their names had a Serakhulle origin. Darame, it says, was a laqab (honorific) acquired from the practice of cultivating a field located on what is vaguely described as ‘the south side of a great river’ (TSK: fo.2). It was the descendants of this Darameba who founded Gunjūr in Bundu to which we shall return in Chapters 2 and 3 below. As for Kharu Muḥammad, Kharu was a Serakhulle’ nickname like Tulli Fadiga, which was acquired through the Fadiga being noted for their liking for honey, which they used for making pious offerings to people.7

Map 2: Jakhanke Dispersions in West Africa

The interest in the Serakhulle background of the early Jakhanke is sustained similarly in respect of al-Ḥājj Sālim’s close family. He is credited with four sons, given in order of age: cUthmān Suware, Yūsūf, Fābu, and Fode, and these were all with him (TSK: fo. 2) when he went to found Diakha-Bambukhu (also called Diakhaba and Diakha-sur-Bafing). His wives, four in number, are equally all Serakhulle: Saghalle Sudūru (mother of her husband’s namesake), Āminata Sudūru (mother of Darameba), Fāṭumata Sudūru (mother of Kharu Muḥammad Fofana-Girasi), and Diba Sudūru (mother of Tulli Fadiga) (TSK: fo. 2). The sons of these women are known by different names, the more formal Islamic baptismal names, given above, and the more common house-names, given in some accounts, some of which occur in the list in TSK. It is clear from these names that at this early stage al-Ḥājj Sālim and his community were not a separate ethnic group but were part of the Serakhulle people, although a definite clerical orientation was taking shape under al-Ḥājj Sālim’s leadership.

It is impossible to be exact about the numerical strength of al-Ḥājj Sālim’s following when he withdrew from Diakha-Masina to Bambukhu. Al-Ḥājj Soriba Jabi estimates that well over 100 qabīlah sections accompanied al-Ḥājj Sālim on his travels, first to Jafunu, where he lived for thirty years, and then to Diakha-Bambukhu (see Sanneh 1974a: 85). This figure of upwards of 100 qabā’il is independently corroborated by a seventeenth century local Arabic chronicle, Aṣl al-Wanqarayīn, to which we shall return in another place (pp. 28–31). Alth...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- MAPS

- FIGURE

- Acknowledgements

- A Note on Orthographical and Similar Conventions

- Introduction: Historical Interpretation and Sources

- 1 The Birth of the Jakhanke Islamic Clerical Tradition c. 1200 – c. 1500

- 2 The Emergence of the Core Clans of Jakhanke Clerics c. 1200 – c. 1700

- 3 Jakhanke Centres in Bundu c. 1700 – c. 1890

- 4 Momodou-Lamin Darame and Patterns of Jakhanke Dispersion in Senegambia: The Nineteenth Century

- 5 The Jakhanke in Futa Jallon: The Nineteenth Century

- 6 Touba and the Colonial Misfortune: The Expropriation of Touba’s Clerical Privilege 1905–1911

- 7 Jakhanke Educational Enterprise

- 8 Prayers, Dreams and Religious Healing

- 9 Slavery, Islam and the Jakhanke

- 10 Conclusions

- Glossary of Arabic and Local Terms

- Archival and Local Sources

- Bibliography

- Index