![]()

1 What circumstances led to this state of affairs?

1.1 Creating cyberspace: a technology toolkit

A great weakness afflicting the ability of social sciences to debate intelligently the implications of cyber in all its forms – cyber security, cyber warfare, cyber espionage, cyber terrorism and cybercrime, among others – is a lack of affinity with the basic scientific underpinnings and technical realities behind cyberspace itself. Many mistakes indeed have been committed in analyses of the subject, betraying a lack of technological understanding that must be corrected. Doing so need not, however, require exhaustive or even particularly deep dives into realms such as computer science (although anybody truly serious about operating in cyber security would be well-advised to do so); what is needed is an accessible tour of the technical realities that make cyberspace a reality, to provide those from social sciences, the humanities and law with a “toolkit” that allows reasoned assessment as to why those core features, which enabled cyberspace as we now know it to operate, matter in security terms.

There are many representations that seek to articulate the layers composing cyberspace, and NATO’s Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCDCOE) is quite right to issue its own caveat before any definition: ‘There are no common definitions for Cyber terms – they are understood to mean different things by different nations/organisations, despite prevalence in mainstream media and in national and international organisation statement.’1 This caveat also applies to the layers readers will encounter throughout literature on matters of cyberspace, the British Ministry of Defence (MoD) states its position that cyberspace consists of six interdependent layers: ‘social; people; persona; information; network; and real.’2 The Internet Telecommunications Union (ITU) also offers a high number of layers, listing computers, computer systems, networks and their computer programs, computer data, content data, traffic data, and users.3 This author chooses to opt for a somewhat more minimalist list, in order to capture the very basic technological essentials that cyberspace requires to operate: the software (logical) level and the physical architecture (geography).4 While there are of course numerous elements that one can cover, for the purposes of this book it is believed that covering these two areas, with five specific aspects of cyberspace activity, will suffice in outlining both the technical operation and their necessary security aspects concerning cyber security.

The software layer

Packet switching

There is little need to try and provide any sort of generic history of the Internet as a whole, this has been mightily achieved from those working on the technical side of cyberspace affairs,5 in social science,6 and in general history.7 The focus here instead is on outlining the key elements of cyberspace, beginning with packet switching. Packet switching is the core element that differentiates8 cyberspace and the Internet from previous means of transmitting information; the immediate predecessor services – the telephone and the telegraph networks – relied on circuit switching. Very simply, circuit switching was a linear, manual connection that had to be maintained for any single call or point of transmission to be successfully made – ‘a set of switches creates a dedicated circuit for signals to go back and forth’;9 were any flaw or failure in the circuit to occur, the transmission would be lost. Not only this, but the entirety of the data needed to flow through that single circuit, leaving it very vulnerable to intercept as a key security concern.

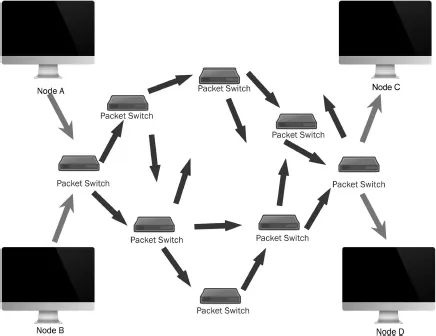

Figure 1.1 Packet switching

A question becomes apparent right from the start, why was packet switching needed at all? The problem set that faced some of the earliest forerunners of cyberspace, in particular those establishing the ARPANET, is best outlined by Isaacson:

Would communication between two places on the network require a dedicated line between them, as a phone call did? Or was there some practical way to allow multiple data streams to share lines simultaneously, sort of like a time-sharing system for phone lines?10

The solution was packet switching:

a special type of store-and-forward switching in which the messages are broken into bite-size units of the exit same size, called packets, which are given address headers describing where they should go. These packets are then sent hopping through the network to their destination by being passed along from node to node, using whatever links are most available at that instant.11

A key aspect to note that is not immediately obvious in Isaacson’s articulation is the fact that those packets are ‘separately transmitted along different routes and then reassembled when they arrive at their destination.’12 As the Internet Society rightly states, the innovation of packet switching was the key element in allowing a core technical principle of what later become known as the Internet to emerge – open architecture networking. This open architecture was made possible by packet switching; without it, the only reliable way of federating networks was to rely on circuit switching.13

The innovation of packet switching raises the necessary question for readers of this work, why does this matter in security terms? First is the recognition that packet switching offers the internetting14 concept a greater degree of resilience than circuit switching could ever provide, which harks back to the classic, simplistic idea that the Internet was built to survive a nuclear war.15 When all works as intended, the packet finds the most efficient route to its destination computer, but should any disruption or blockage occur, the packet simply ‘consults a routine table to determine the next best step and to send the packet closer to its destination.’16 The ability for a data packet to reroute time and again throughout the network, even when encountering blocked, denied, or disrupted nodes, effectively circumvents the primary weakness pervasive in the circuit switching model, and provides a network ability to survive the disruption or even destruction of portions of its nodes. Interception or denial of communications becomes a much harder proposition to achieve with such technology, as it is much harder to know what routes are being taken or even how to effectively deny service in a targeted fashion.

Secondly, the sheer resilience of cyberspace networks poses a security challenge to the state itself, one that Dunn Cavelty and Brunner have already stated, that increasing internationalisation and privatisation have been enhanced by these technological developments, diminishing the importance of the state.17 That diminishment lies in the reduction of the state’s monopoly over information itself, enabling the creation of new breeds of non-state actors to operate in this low cost of entree space. Actors such as WikiLeaks, Anonymous, and the range of advanced persistent threat (APT) groups are the clearest example of those widely known about, who have delivered disproportionate effect through their actions in cyberspace. If a state wishes to throttle and block the dissemination of information, packet switching is a reliable and automated means of ensuring that the packets simply find the most reliable route – through, around, and beyond sovereign territorial boundaries – to its recipient. If ‘Information is a key way by which … power operates and develops,’18 then packet switching is a key enabler for the distribution of information, and therefore power, away from the state and to the individual.

TCP/IP

If packet switching enabled the ability to send data across and between potentially unlimited numbers of networks, the next question to be raised was, by which standard would computers, networks, and packets communicate with each other? This problem set is well articulated by Tarnoff, in that ‘getting networks to talk to one another – internetworking – posed a whole new series of difficulties, because the networks spoke alien and incompatible dialects.’19 Data simply could not be exchanged and read without a universal common language for understanding on all sides. The requirement, then, was to build a standard language by which all networks could operate, ensuring that networks worldwide could seamlessly accept and exchange the packets being sent. Without a shared protocol language, the needs of an open architecture network environment could not be met, but the protocol that solved the problem would come to be called the Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP).

TCP/IP ‘provided all the transport and forwarding services in the Internet.’20 Several versions were, as expected, necessary in order to provide the required level of reliability in global interchanging, making use of the underlying network service of cyberspace, in order to cope with the prospect of missing or lost data packets. TCP is the top layer of the protocol, which is responsible for accepting large segments of data and breaking it down into packets for sending; IP is the bottom layer, responsible for the locational aspects of sending data, allowing packets to get to the correct destination.21

TCP/IP requires four layers to operate and are the foundation on which data exchange at the software level occurs in cyberspace. These layers are named the DARPA model (shown in Figure 1.2): the Application Layer, the Host-to-Host Transport Layer, the Internet Layer, and the Network Interface Layer. Applications access the services of the other three layers through the Application Layer, which determines the protocols needed to exchange information for whichever application is being used. T...