![]()

1

Introduction

The Akhbār-i-Moghūlān dar Anbāneh-ye Quṭb by Quṭb al-Dīn Maḥmūd ibn Mascūd Shīrāzī

The period between circa 1260 and the early 1300s has been described as a historiographical desert with the dearth of historical chronicles and absence of historical accounts having been caused by the Iranian Muslim world’s apprehension at a prolonged period of infidel rule, a fatrat, 1 or interregnum, which ended with the production of the remarkable compendium of histories by the researchers of the Rab’-Rashīdī, Rashīd al-Dīn’s academy in Tabriz. 2 Their collective hard work under the guidance of the polymath and exceptionally talented Rashīd al-Dīn produced the world’s first universal history, the Jāmac al-tavārīkh, to which the present work donated a sprinkling of information and words.

Juwaynī ended his own chronicle on the eve of the fall of Baghdad following the destruction of Alamut and the end to the ‘blasphemous and heretical’ regime of the Ismailis. Some saw ominous meaning in his silence on the ‘events’, the ‘vāqi’a’ of Baghdad, a silence that seemed to be broken only with the re-establishment of Muslim rule again in Iran.

However, Juwaynī was only partly silent and for good reason. First, his colleague, Naṡīr al-Dīn Ṫūsī (1201–74) provided a final chapter to Juwaynī’s History of the World Conqueror, which covered the ‘events’ in Baghdad, while his own account finished more appropriately with the end of an era rather than the start of a new age. But perhaps more importantly, ‘Aṫā Malik Juwaynī was no longer a court adviser with time on his hands to write and research at leisure but the governor of a large and important cosmopolis. Not only was his new position time consuming, but it was politically sensitive and his words and pronouncements were public property with his every syllable carrying political weight. As Baghdad’s governor, his words were far more than likely to ruffle the feathers of someone, somewhere, about something than as Hulegu’s PA whose thoughts and opinions would have had far more limited impact.

In fact, during this early period of Ilkhanid rule, local histories continued to be written, and Rashīd al-Dīn’s collection of chronicles is just that, a collection of notes, observations, accounts, and records, which was being amassed in the decades prior to Ghazan’s enthronement. The Ilkhans might have been infidels but they had been recognised as legitimate Iranian monarchs from the beginning as the great Sunni theologian, Bayḍawī, was keen to attest with his regularly updated historical pocket book, Niżām al-tavārīkh. The period between 1282 and 1295 was a period of unusually disruptive political activity in Ilkhanid Iran, a dynastic period (1258–1335) of general political stability, cultural prosperity, and certainly in the earlier decades, economic growth. The Akhbār only came to light a few years ago, not long after the discovery of the remarkable Safīna-ye Tabrīz dating from circa 1322–35 which certainly maintains the hope and possibility that other chronicles, short histories, and historical accounts might continue to come to light in the musty and neglected storerooms of Iranian academia.

The Akhbār-i Moghūlān dar Anbāneh Quṭb penned though not necessarily authored by Quṭb al-Dīn Shīrāzī (1236–1311), 3 outlines the early years of the Chinggisid empire, recounts the rule of Hulegu Khan and his son Abaqa, and finally, details the travails and ultimate demise and death of Abaqa’s brother and would be successor, Ahmad Tegudar. It is an original and independent source and though it covers well-known events and personalities, it throws new light on these events and makes some startling and controversial claims concerning other matters that are only lightly touched upon elsewhere. Shīrāzī was a well-known, highly respected figure with access to key members of the ruling elite and to other centres of establishment power and influence including the ulema. He supplemented his scientific work with copy writing manuscripts which is why the authorship but not the penmanship of this work is in question. 4

Quṭb al-Dīn Maḥmūd ibn Mascūd Shīrāzī

Quṭb al-Dīn Maḥmūd ibn Mascūd Shīrāzī (634–710/1236–1311) is best known for his association with Naṣīr al-Dīn Ṭūsī (d.1274) and his astrological and scientific work at the famous observatory of Maragha, in Iranian Azerbaijan. Born into a cultured and educated family, Quṭb al-Dīn received medical training from his father, Żiāʾ al-Dīn Mascud Kāzerunī, a well-connected physician and Sufi, who died when the boy was only 14, leaving his son’s schooling in the hands of some of Shiraz’s leading scholars. The young Quṭb al-Dīn delved into the complexities of Avicenna’s Qānun along with Fakhr al-Dīn’s commentaries and reputedly raised many issues with his tutors which he determined one day to answer in his own commentary. He succeeded his father at the Mozarfarī hospital in Shiraz as an ophthalmolo-gist while still a teenager and continued his education under such luminaries of the Qānun as Kamāl al-Dīn Abu al-Khayr, Sharāf al-Dīn Zakī Bushkānī, and Shams al-Dīn Moḥammad Kishī until the age of about 24. He left the hospital to devote himself full time to scholarly pursuits when he heard about developments in the north of the country which offered an opportunity too great to ignore. Shīrāzī left Shiraz in 1260 and he is believed to have finally arrived at Ṭūsī’s Rasadkhāna in 1262.

The Maragha complex of Ṭūsī’s Rasadkhāna had gained in renown and stature as the Ilkhanate grew and benefitted from growing political stability, expanding trade links, and increasing cultural exchange. The complex comprised the famous observatory, Ṭūsī’s library amassed from the intellectual riches of both Alamut and, much to the chagrin of the exiled Arabs in Cairo, of Baghdad’s famed collections, a madressah and mosque, and the lecture halls and research laboratories of the Rasadkhāna. Ibn Fuwaṭī, Ṭūsī’s chief librarian, who had been rescued from Baghdad, composed a mammoth biographical dictionary during his time in Maragha, based on information gleaned from the many scholars, researchers, and merchant travellers who availed themselves of this seat of learning which had fast been gaining an international as well as a regional reputation. Only the volumes of his biographical dictionary covering ‘names’ from cayn to mīm have survived and even these extant folios are a summary of the lost originals. 5 The Mamluk scholars in Cairo could only fume in resentful frustration as Maragha built its reputation on the stolen waqf-supported, intellectual wealth of Baghdad that they considered rightfully theirs.

Figure 1.1 Tusi’s Observatory, The Rasdakhana, Maragha

Their spokesman, the historian and man-of-letters, Ibn Aybak al-Ṣafadī (1296–1363) cursed Ṭūsī whom he accused of having persuaded Hulegu to award him Baghdad’s libraries, 400,000 tomes, as acknowledgment for services rendered and advice given and expressed ‘utter derision and humiliation’ when he thought of the treachery of Ibn al-cAlqamī who had been in secret correspondence with the approaching enemies of his master, the Caliph al-Mustacṣim. 6 Certainly, the Persian scholars and clerics who flocked to Maragha felt no scruples or guilt in availing themselves of

Figure 1.2 Observatory foundations, Maragha

Ṭūsī’s glittering prize and would not have agreed with al-Ṣafadī’s assessment of Hulegu’s honoured senior adviser Ṭūsī, as a thief and embezzler. Hulegu gave Ṭūsī authority over the distribution and control of waqfs, a highly controversial position, which allowed the wazir to lavish funds on his prestigious project, the Rasadkhāna, and freed Hulegu from having to find funding himself for such an expensive commitment. For Ṣafadī, Hulegu was in a win/win situation; he avoided financial responsibility for this monetary sponge while earning the loyalty of a key Iranian player for actualising his pet project. 7

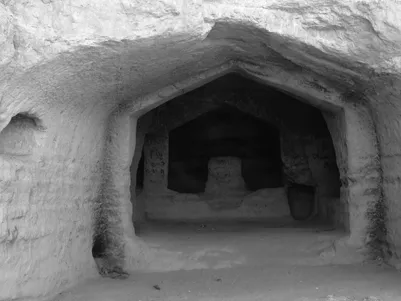

The complex was a magnet and other key political and cultural figures associated themselves with the Rasadkhāna. The existence of a collection of modified caves dug deep into the steep sides of the hill towering over the market town of Maragha is believed, though not proven, to be the remains of the Syriac church constructed on Hulegu’s orders, for the bishop, Abu Faraj Mor Gregorios Bar Hebraeus. The cave entrances lie in the hillside below the site of the observatory which crowns the hilltop, giving the astronomers a panoramic view of the town, the mountain to the north, and the undulating land levelling off towards Lake Urmia in the west. Bar Hebraeus wrote his own great chronology in Maragha and in the introduction to this great historical work he expresses his gratitude and indebtedness to Ṭūsī and his library.

From its inauguration, the observatory attracted scholars from all over Iran and beyond. Shīrāzī resumed his education under Ṭūsī, adding astronomy to medicine, ophthalmology, the Qānun, and the other sciences in which he had already been schooled. Theology had of course comprised a major element of his early education and he had received his Kherqā, a Sufi robe, from Najīb-al-Dīn Ali b. Bozḡosh Shīrāzī. His father had received his own Kherqā from the renowned Shehāb-al-Dīn cUmar Sohravardī. Shīrāzī had been a precocious and avid student of theology, but he was a true poly-math and he matched Ṭūsī’s passion for the stars, becoming instrumental in the composition of the astronomical tables (Zij) for which the Maragha observatory became justly celebrated.

A revealing anecdote which has survived from the comparatively short time that Shīrāzī stayed in Maragha, recounts how the Ilkhan, Hulegu, piqued with his trusted adviser, Ṭūsī, revealed to the young scholar that there was only one reason that he did not have Ṭūsī executed. The Ilkhan confided in Shīrāzī that he needed Ṭūsī to finish the Zij to which revelation the earnest Quṭb al-Dīn responded by assuring Hulegu that he should not fear because he would be quite capable of finishing the tables for him

Figure 1.3 Bar Hebraeus’ Church, beneath Tusi’s Observatory

without Ṭūsī’s assistance. Later, the bemused Ṭūsī asked his star pupil if this story were true, and the guileless Quṭb assured him that it was. Warned that Hulegu was unlikely to have appreciated Shīrāzī’s ironic banter, Quṭb assured his master that he had not been joking but had been quite serious. 8 It is worth noting that in Ṭūsī’s later records of the Rasadkhāna, Shīrāzī’s name is absent from the list of his assistants despite the great deal of important work that he had devoted to the composition of the tables. Rashīd al-Dīn and Waṣṣāf similarly omit mention of Quṭb al-Dīn in their accounts of the Maragha observatory. No mention of the observatory or library is made in “Shīrāzī’s” 9 chronicle though this is hardly the only important omission. However, confirmation of Shīrāzī’s crucial contribution to the Zij is attested to indirectly when in his will, the waṣiya, Ṭūsī advises his son, Aṣil-al-Din, to work with Shīrāzī on the completion of the astronomical tables. The significance of these omissions is a matter for conjecture.

As well as erudite and voluminous commentaries and analyses o...