- 246 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Privatisation and the Welfare State

About this book

Originally published in 1984, Privatisation and the Welfare State brings together a distinguished set of experts on the Welfare State and its main policy areas of health care, housing, education and transport. Each chapter provides some much-needed analysis of privatisation policies in areas where, too often, political rhetoric is allowed to dominate discussion. The book makes a major contribution to the reader's understanding of the complex issues involved in this controversial area of social policy. As the first systematic evaluation of a broad range of welfare state privatisation proposals, it is essential reading for economists, social administrators, and political scientists.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Privatisation and the Welfare State by Julian Le Grand,Ray Robinson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Privatisation and the Welfare State: An Introduction

JULIAN LE GRAND and RAY ROBINSON

In recent years the ‘welfare state’ has been the object of a sustained intellectual attack. A substantial body of economists has for some time been uneasy about the public provision and tax financing in the United Kingdom of certain commodities that are provided through the private market system in some other countries. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s their views were promoted through a series of publications from the Institute of Economic Affairs, but they remained – as far as mainstream policy decisions were concerned – an academic curiosity. The election of the Thatcher government changed all this. Since 1979, the government’s commitment to a private market philosophy has led to a series of proposals or decisions designed to replace the ‘welfare state’ systems of collective provision and finance with more privatised systems. Examples include proposals to introduce private insurance funding to the National Health Service, contracting out hospital cleaning and catering, education vouchers, replacing student grants by loans, running public transport on a break-even basis, the sale of council houses and, as part of the return to Victorian values, the replacement of state redistribution by private charity. As this process gathers momentum, there is an urgent need to subject the claims made for privatisation to serious scrutiny, to establish the allocative and distributive consequences, and to reassess some of the fundamental economic aims of welfare state provision. This is the aim of this book.

In this introductory chapter we set the scene for the individual contributions that follow. We begin with some facts and figures concerning the rise – and recent fall – of the welfare state. This is followed by a discussion of the meaning of the term ‘privatisation’, and then, to open the debate, we present a review of the principal arguments, both for and against. The review is not designed to offer a conclusion; rather, it is more a taxonomy, designed to place the following chapters in context.

THE RISE AND FALL OF THE WELFARE STATE

Although there is no precise definition of the bounds of the welfare state, it is possible to specify the main programmes that are normally identified as parts of it. First, there is the social security system, which makes income transfers from taxpayers to benefit recipients in the form of cash payments. These include the social insurance based programmes emphasised in the Beveridge Report (1942), through which individuals’ contributions provide entitlement to benefits (i.e. sickness benefits, short-term unemployment benefits and retirement pensions), and also increasingly – in the face of continuing high levels of long-term unemployment – non-contributory payments such as supplementary benefits. Second, there are benefits in kind, which are provided via free health care, education and various personal social services (e.g. the services of social workers, home-helps, meals-on-wheels, etc.) Third, there is a range of price subsidies designed to reduce the cost to consumers of certain commodities deemed socially desirable. These include rent subsidies, housing improvement grants and public transport subsidies.

The long-term growth of public expenditure upon these programmes has been well documented (Sleeman, 1979; Gordon, 1982; Judge, 1982a). Judge (1982a, p. 31) estimates that social expenditure rose by almost 250 per cent in real terms between 1951 and 1979; this represents an increase in its share of GNP from 16.1 per cent to 28.3 per cent. Recent figures contained in The Government's Expenditure Plans 1983/84–1985/86 (HMSO, 1983a) show that expenditure on the welfare state – defined in terms of the categories shown in Table 1.1 (which are slightly different from those used by Judge) – accounted for about 25 per cent of GNP by 1981/2. As the table shows, nearly one-half of the total budget was accounted for by the social security system: of this, approximately 43 per cent was spent on retirement pensions, 17 per cent on supplementary benefit payments, 12 per cent on child benefits and 6 per cent on unemployment benefits. Spending on health and personal social services, and on education and science, accounted for about one-fifth of total expenditure each, while transport and housing represented about 5 per cent each.

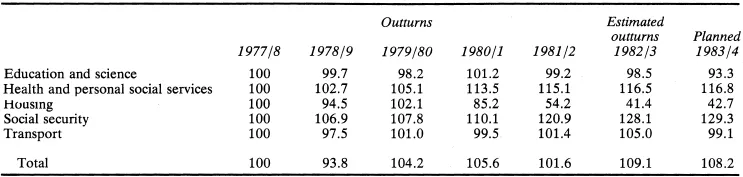

Since the mid 1970s, the rate of growth of welfare state expenditure has been severely checked and in some sectors expenditure in real terms has actually fallen. This process, which arose initially because of the perceived need to limit public expenditure in the interests of macroeconomic policy, has been accentuated by recent policies on privatisation. Table 1.2 presents indices of the levels of real expenditure for the main welfare state programmes 1977/8–1982/3 and planned expenditure for 1983/4. The most striking feature of the table is the scale of reductions in housing expenditure: planned expenditure in 1983/4 is only a little over 40 per cent of the 1977/8 level. Education has also suffered reductions in real expenditure in recent years with a 5 per cent cut planned for 1983/4. Only in the social security sector has there been an increase in expenditure, particularly since 1980/1. Expenditure plans for the government’s current planning period (i.e. up to 1985/6) are now only published in cash terms. However, with no programme planned to increase its cash budget by more than 12 per cent over the two-year period 1983/4–1985/6, it is clear that government plans include little scope for any expansion of real resources devoted to the welfare state. Privatisation is clearly designed to cater for an increasing proportion of welfare needs.

Table 1.1 Welfare state expenditure, 1981/2 (current prices)

| £ million | % of total | |

| Education and science | 11,828 | 19.7 |

| Health and personal social services | 12,751 | 21.2 |

| Housing | 3,137 | 5.2 |

| Social security | 28,510 | 47.4 |

| Transport | 3,898 | 6.5 |

Total | 60,124 | 100.0 |

Source: The Government’s Expenditure Plans, 1983/84–1985/86, Cmnd 8789–1, HMSO, February 1983, Table 1.7, p. 11.

THE MEANING OF PRIVATISATION

In the most general sense, any privatisation proposal involves the rolling back of the activities of the state. The latter vary widely from welfare area to welfare area; and so, therefore, do the former. Hence, in order properly to understand the various meanings that the term privatisation can take on, it is necessary to have some method of classifying the different activities of the state.

The state can involve itself in an area of social and economic activity in any of three ways: provision, subsidy or regulation. That is, it can provide a particular commodity itself through owning and operating the relevant institutions and employing the relevant personnel. It can subsidise the commodity by using public funds to lower the commodity’s price below the one that would otherwise obtain; sometimes, the price is lowered to zero, the commodity being provided free. Or the state can regulate the provision of the commodity, regulating its quality, its quantity or its price.

Table 1.2 Welfare state expenditure, 1977/8–1983/4 (1977/4=100)

Source: The Government’s Expenditure Plans 1983/84–1985/86, Cmnd 8789–1, HMSO, February 1983, Table 1.14, p. 17.

In most of the activities encompassed by the welfare state in Britain, it uses all three. For instance, under the National Health Service, the state provides health care through the public provision of hospitals and the employment of general practitioners; it subsidises health care by providing it free, or largely free, at the point of use; and it regulates the quality of the providers of health care through qualification requirements. In education, the state regulates the quality of schools through an inspectorate; it also regulates the quantity of education provided by, inter alia, compelling children to attend school between the ages of 5 and 16. It owns and operates most educational institutions, from primary schools to universities. And it provides most education free, or largely so; in some cases (such as most students in higher education), it even pays people to attend.

The quality of all types of housing is regulated through a variety of statutory requirements, concerning layout, appearance, structural soundness, sanitation, etc. Otherwise the form of state intervention varies between tenures. Council housing is, of course, state provided; council tenants have also traditionally been subsidised, through general subsidies and rent rebates. In the private sector, rents are regulated, while poor tenants have been subsidised through the rent allowance scheme. (Assistance to tenants, both public and private, has recently been combined in one scheme – a unified housing benefit.) The owner-occupied sector is subsidised through direct grants, such as those for house repairs and improvements; it is also heavily subsidised through various ‘tax expenditures’, such as the exemption of owner-occupied houses from capital gains tax, and the non-taxation of imputed income.

In the personal social services, social workers and residential homes for children, for the mentally handicapped and for the elderly are provided and subsidised by the state. The quality of the service is regulated, through qualification requirements and inspections.

Most public transport undertakings are owned and operated by the state; they are also heavily subsidised. Private undertakings, such as private coach operators, are regulated.

This categorisation of state activities can even be carried through to its activities in the social security field. State social security serves two functions: the provision of insurance against loss of income due to sickness, unemployment and old age, and the redistribution of private income. The state can thus be viewed as ‘providing’ two commodities: insurance and redistribution. In each case, it regulates the quantity provided, through its use of eligibility requirements; and, of course, it subsidises them through its use of public funds to pay the relevant benefits.

Having described the various ways in which the state can intervene, we are now in a position to classify the various kinds of privatisation. Not surprisingly, they parallel the three types of intervention. First, there are forms of privatisation that involve a reduction in state provision. Examples include the sale of council houses, the closing of local authority residential homes, the expansion of privately provided medical care, the contracting out of hospital cleaning and catering, and most education voucher schemes. Into this category also fall proposals for privatising the social security system, such as relying more heavily on private insurance companies to provide sickness and other ‘insurable’ benefits or on private charities for redistribution. Second, privatisation can involve a reduction in state subsidy. Examples here include the reduction in subsidies to remaining council tenants, the introduction of charges (or an increase in existing ones) for services received under the National Health Service, the replacement of student grants by student loans, and reductions in subsidy to public transport. Third, privatisation can imply a reduction in state regulation. Examples are the lifting of restrictions on competition between private and public bus companies, and the easing of rent controls.

However, privatisation schemes differ not only in the type of state intervention whose reduction or elimination they require. They also differ in what is proposed in its stead. Some propose simply the replacement of the state by the market; the relevant service should be undertaken by profit-maximising entrepreneurs operating in a competitive unregulated environment. Other schemes involve the replacement of one form of state activity by another: a reduction in state provision, for example, coupled with an increase in regulation of private providers. And yet others want to encourage the activities of organisations that are neither the conventional profit-maximising firm nor the state enterprise: charities and other non-profit-making voluntary organisations, workers’ co-operatives, consumer co-operatives, community associations.

Thus, privatisation can take many forms. A simple interpretation, such as the replacement of the state by the market, will not suffice. The kind of state intervention to be replaced must be specified; so too must be the type of non-state institution that will replace it. For this reason, it is not easy to argue about the merits and de-merits of privatisation in the abstract; the arguments will vary according to the types of state and private activities involved.

PRIVATISATION: FOR AND AGAINST

The case for privatisation rests upon the supposed deficiencies of the various forms of state intervention and on the ability of some form of privatised system to remedy them. In particular, the welfare state is said to have failed to achieve some of its aims, such as the promotion of economic efficiency and of social justice (usually interpreted in terms of greater equality of one kind or another), while at the same time it has adversely affected other ideals that society might have, such as the preservation of individual liberty. Privatised systems, in contrast, are said to be both efficient and conducive to the exercise of liberty; it has also been argued that they are on occasion more equal. Views such as these come from a large number of sources. Among the principal critics of the welfare state are Friedrich von Hayek, Milton Friedman, the ‘Public Choice’ School developed from the work of James Buchanan, Anthony Downs and Gordon Tullock, and the writers associated with the Institute of Economic Affairs. A detailed description (and ascription) of their arguments can be found in Part I of Bosanquet (1983). In what follows we elaborate these views and put forward some of the counter-arguments. (Many of the issues are discussed in more detail in Le Grand and Robinson, 1984.)

Efficiency

The welfare state is said to create inefficiency in two rather different ways. First, it is argued that state social services encourage a wasteful use of resources by both their suppliers and their consumers. Second, the welfare state is supposed to damage the productive power of the economy through its effects on the incentives to work and to save. Although the second charge could be also levelled at state subsidised social services, it is usually confined to the social security system.

The inefficiency of state social services varies with the type of state intervention considered. State provision is supposedly inefficient because services are not supplied at minimum cost. Individuals in state organisations pursue their own interests in the same way as individuals in private ones do; they all want jobs that are rewarding (in terms of money, status and power), satisfying and as secure as possible. However, in their pursuit of those ends, public employees are not faced with the same constraints as private ones; in particular, their ‘firms’ cannot be driven out of business or be taken over, even if they provide an inefficient service. Hence they will engage in practices that serve their own ends at the expense of their clients. Hours of work will be reduced, work practices will be inefficient, wages will be too high, other elements of remuneration such as pension schemes wil be too generous, and so on. Generally, resources will be wasted because the public sector lacks accountability.

This argument has been criticised as taking simultaneously too pessimistic a view of public employees’ activities and too optimistic a view of those of private employees. To assume that public employees nev...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- About the Contributors

- Preface

- 1 Privatisation and the Welfare State: An Introduction: Julian Le Grand and Ray Robinson

- PART I: GENERAL PRINCIPLES AND STRATEGIES

- PART II: POLICY ISSUES

- References

- Index