1 ‘A Large Football Stadium with a College Attached’

1920s Collegiate Youth Culture

With its premiere at the start of the 1925 fall semester, The Freshman was poised to capitalize on American mass culture’s fascination with the burgeoning subculture of 1920s campus life. Due to sharp rises in attendance and the popularity of intercollegiate sports, college had become both a means for and a fantasy of class mobility for a greater number of Americans than ever before. Yet as college was still limited to a relatively small portion of the population, this fantasy had little to do with academic life. At the end of the decade, literary critic and Princeton dean Christian Gauss published Life in College (1930), which narrated the sum of his observations on the altered nature of the 1920s American university. College, he argued, was no longer solely oriented toward the process of maturation but had become a means of prolonging adolescence through an emphasis on fraternities, athletic events, and dances, creating a community of peers largely outside of the purview of adults. For Gauss, the 1920s university had transformed into ‘a kind of glorified playground’ where students of similar ages refashioned norms of conduct according to their own standards. In his view, ‘It is this too exclusively adolescent character of American college life that also results in that general range of excesses known as “the collegiate”’ (Gauss, 1930: 30).

In the 1920s, the term ‘collegiate’ came to stand in for both the exclusive subculture of university life and a style that exceeded the bounds of campus. While the turn of the century witnessed the university’s transformation from a training ground for clergy and teachers into a ‘fashionable and prestigious’ activity for the nation’s elite, the 1920s marked the period in which the college and the style of its inhabitants spread to the masses (Thelin, 2011: 156). As this chapter will discuss, 1920s campus culture occupied a liminal position as a subculture marked by its difference from the larger parent culture and a rapidly growing form of mass culture in which collegiate styles were sold to the young and their elders alike. In the 1920s, modern youth’s association with jazz, alcohol, and more liberated sexual attitudes permeated popular culture, and college men and women served as its avatars of style. However, unlike later youth cultures, which emphasized their overall ideological differences from parent culture, 1920s campus youth refused only stylistic norms. College students in the 1920s may have asserted their distinct sense of themselves as a generation who obeyed their own rules, but their ideologies were firmly of the middle class.

This chapter will discuss the distinctive aspects of 1920s campus culture as subculture, mass culture, and popular culture before and after the premiere of The Freshman. Lloyd’s film marked a transitional moment in 1920s youth culture, as The Freshman simultaneously constituted a parody and a popularization of the clichés of 1920s college life as a generationally exclusive enclave. As The Freshman depicts, prior to his arrival on campus, naïve Harold Lamb (Lloyd) foregoes Aristotle and Plato in his preparation for college, instead employing more up-to-date guides: a pamphlet entitled ‘Clever College Clothes – An Authoritative Pamphlet on what the College Man Will Wear,’ a manual on ‘How to Play Football,’ and ‘College Yells,’ a handbook for varsity sports fans. The inclusion of these alternative primers points to the prevailing characterization of the college man as solely interested in clothes and sports, which this chapter will explore in more detail, that fueled a new conception of youth as a commodity. Rather than solely a stage of life, youth in the 1920s was predicated on a new form of embodied participation born of the modern, urban industrial era. In place of working on his on-the-field skills, The Freshman introduces Harold practicing being a football fan through a series of vociferous football cheers which disrupt his middle-class home and parents, particularly his father, an amateur ham radio operator who mistakes Harold’s vehement yells for transmissions from China. As I will trace, the spread of collegiate football spectatorship as a new national pastime enshrined 1920s collegiate culture as popular culture accessible to all, irrespective of one’s age or class. College football fandom in the 1920s transformed spectatorship from a passive to an active pursuit, promoting a sense of participation in the events on a field and solidarity with other fans, which bled over into other mass viewing activities, including the cinema. In line with the American university’s orientation toward training for the middle class, the ethos of 1920s college sports spectatorship initiated its participants into the importance of conforming to one’s peers while defying middle-class adult standards of conduct. Just as The Freshman introduced its main setting, Tate University, with the pithy caption as ‘a large football stadium with a college attached,’ 1920s campus youth were depicted, both by mass culture and by their own discourse, as a peer-oriented leisure culture focused on conformity, conspicuous consumption, and corporate action as training for the middle class.

A Kind of Glorified Playground: 1920s Collegiate Subculture

Long before the teenage rebels of the 1950s and campus protestors of the 1960s, the 1920s marked the emergence of a discrete youth culture in the United States. Youth historian Paula Fass (1979: 122) argues for this fledgling peer community as the first American youth culture, as it constituted a ‘culture that was fed by the larger culture but that was also distinct and separate.’ Following Fass, Simon Frith (1987: 191) notes that the three aspects that characterized 1920s campus life as the first American youth culture were also what distinguished it from the youth cultures of the 1950s and 1960s. As opposed to the 1960s counterculture’s rejection of the values of a broader society, 1920s campus culture was based on conformity to the norms of the campus as isolated from larger concerns. Second, 1920s college culture ‘was not, even at the time, an expression of generational conflict’ (191). Instead of hostility toward the larger parent culture, 1920s campus culture presented a culture of difference based on an ethos of personal liberty expressed through consumption. Finally, as opposed to 1950s and 1960s teenagers’ adoption of working-class styles and values, in the 1920s, ‘the middle-class way of leisure became the model for working-class youth’ (192).

From this description, 1920s campus culture comes into view as a burgeoning subculture through its emphasis on consumption. As Dick Hebdige (2010: 17) argues, youth subcultures are marked not by overt resistance to parent culture, instead they challenge the hegemony ‘obliquely’ through style. As ‘cultures of conspicuous consumption,’ subcultures reappropriate mass-produced commodities (such as safety pins for punks or public walls for street artists) to offer a ‘symbolic violation of the social order’ rather than an actual one, asserting their individual identity as a group (18–19, 103). Angela McRobbie (2000: 33) similarly makes the case that subcultures allow their members ‘a sense of oppositional sociality, an unambiguous pleasure in style, a disruptive public identity and a set of collective fantasies.’ In this section, I will trace the emergence of 1920s campus youth subculture in these terms. As I will discuss, the first American youth culture asserted its refusal of adulthood through a distinctive style of peer-oriented conspicuous consumption nurtured by both the cloistered college campus and a swelling national university culture.

In the 1920s, letter sweaters, plus fours (knickerbockers described by the length they fell below the knee), raccoon coats, autographed ‘slicker’ raincoats, and a proliferation of proms and football games dominated the popular conception of campus youth culture as the university transformed from a small training ground for clergy and the professional elite into a mass middle-class educational institution (D.O. Levine, 1987: 113–35). Between 1900 and 1930, college and university enrollment in the United States expanded threefold, with the largest absolute increase in the 1920s. At many state universities, including the University of Illinois and Ohio State, the effect was meteoric: the student bodies at both institutions doubled between 1919 and 1922, from 3,000 to 6,000 and 4,000 to 8,000, respectively (Fass, 1979: 124). Private universities followed suit. New York University reported doubling its total enrollment (in undergraduate, graduate, and nondegree granting programs) between 1921 and 1927, making it one of the largest colleges of arts and sciences in the country (‘Over 32,700 Enrolled in University Courses,’ 1927). The Ohio State Daily Lantern further reported that Columbia, Harvard, Northwestern, and the University of Chicago each enrolled over 10,000 students, including part-time and summer enrollment, by 1927 (‘Mass Minds,’ 1927). This rapid increase can be attributed to several factors: children of the working class sought admission to college in greater numbers as industrialization made higher education a necessary means to escape ‘dead-end’ factory jobs; the 1920s marked a sizable increase in the population aged 15–24 relative to the age group below; and during this period, the middle-class family continued its transition toward producing fewer children and focusing on those children’s individual training for the future (Fass, 1979: 46, 58–59; Kett, 1979: 150–52). By the end of the decade, nearly 20% of the college-age population was enrolled in some type of higher educational institution (Fass, 1979: 124).

More important to the development of the 1920s campus subculture was the shift in the overall makeup and orientation of the college population. Following the gradual contraction of the age range in American colleges between 1850 and 1900 to a concentration between 18 and 22 years of age, 1920s college students in general belonged to the same generation and identified themselves as such (Kett, 1979: 126–27). Fass (1979: 324–30) notes the effect of World War I on the 1920s college generation in their perceived self-consciousness as a group in the first half of the decade. She argues that although youth rejected the norms and standards of the older generation, which they considered to have caused the war, they did not eschew norms in general. They merely replaced earlier standards of conduct and morality with their own. In this new world of ‘attacking the immutability of eternal verities and romantic fallacies inherited from a dead past’ and the decreased inability of educational administrations to order and discipline their ballooning student bodies, college and university students in the 1920s looked to each other rather than adults for models of style and behavior (358). As a consequence, the 1920s college became a source for socialization rather than intellectual pursuits (Fass, 1979: 120; Levine, 1987: 115–23). What marked 1920s college culture as new then was not just its particular fashions or activities, but its transformation into an adolescent rite of passage.

American college youth in the 1920s characterized the growing trend for prolonging adolescence in favor of better employment prospects, epitomizing the adolescent in-between stage of increased social independence tempered by financial dependence. College men and women thus enjoyed a unique position in 1920s American society – defined by ample leisure time, little adult supervision, and an extended delay of adult responsibilities. 1920s college life also boasted remarkable homogeneity, not only in its fashions, but also in terms of experience. The majority of college and university students during this era filled their time with three types of activities: those offered by the formal structure of the institution (e.g. classes), semi-formal extracurricular activities that were student-run with the acknowledgment and blessing of the administration, and informal student interactions that included fraternities, sororities, dating, and going to the cinema (Fass, 1979: 131–34). The latter interactions made up the bulk of the leisure time for college youth, effectively reconfiguring university life into a world of the students’ own making. As a national collegiate culture was emerging from a growing awareness of the uniformity of the college experience, peer-oriented activities represented an intrinsic part of that experience.

Fraternities and sororities provide the clearest example of the peer-oriented subculture of 1920s college life. While the existence of American college fraternities dates to 1825 with the founding of Kappa Alpha at Union College, exploding enrollments in the 1920s led to the rapid growth of fraternities and sororities to meet the housing and boarding demands for which university facilities were otherwise unprepared. The number of national fraternity and sorority chapters more than doubled between 1912 and 1930, and the total number of fraternity houses increased from nearly 800 in 1920 to 1874 in 1929 (Fass, 1979: 142–43). By 1930, more than a third of all students were members of a fraternity or sorority, a shift that also reflected the transformation in campus status away from one’s academic class (freshman, sophomore, junior, senior) as one could no longer claim to know a significant amount of one’s classmates. Greek life now took up the task of initiating students to college and enforcing social norms. It was no longer enough to enroll in college to become part of the peer culture: ‘[t]here were now specific peer-determined criteria to be met’ which enforced homogeneity among collegians who hoped to rise in status by emulating fraternity standards of style and demeanor (147–48).

Peer-oriented education consisted of a combination of emulation and reinforcement, known as ‘razzing.’ In the post-World War I era, ‘razzing’ was a common collegiate practice aimed at humiliating students who did not uphold norms of dress and conduct set by their peers. ‘To razz someone was simply to deride his peculiarities and to confront him with his faults,’ in other words, to shame another undergraduate and to do so publicly (161). In November 1922, the Ohio State Daily Lantern published an editorial on razzing as a constructive ‘sport.’ ‘If there is one thing that distinguishes the college man from others,’ the Daily Lantern opined, ‘it is his ability to take a good “razzing”’ (‘“Razzing” as a Sport,’ 1922). Razzing was thus considered not only a means of improvement for individuals who fell short of the mark but also a way to signal one’s belonging to the university community through submission to the norms of the group.

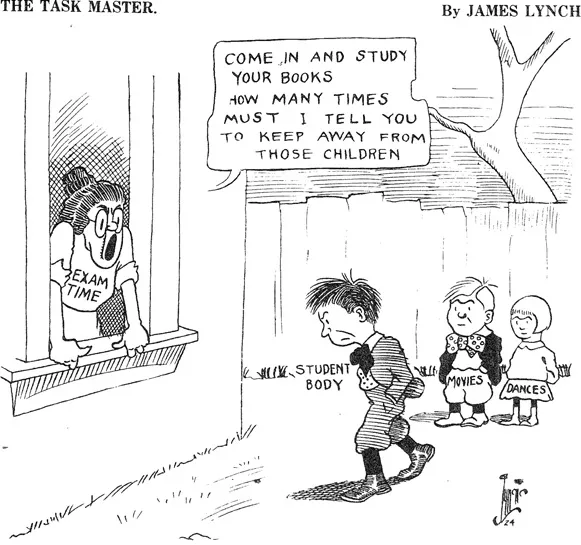

In their own discourse, college students readily acknowledged the importance of peer-oriented social activities like fraternities, sororities, dating, and cinema over academic pursuits controlled by the older generation (see Figure 1.1). On January 10, 1923, the student-run New York University Daily News (Lynch, 1923) published a cartoon entitled ‘The Task Master,’ in which a wiry-haired boy labeled ‘Student Body’ trudges reluctantly away from two other children – a little girl tagged ‘Dances’ and another boy identified as ‘Movies’ – toward an open window, where ‘Exam Time,’ an older woman with glasses, a severe pompadour, and a strident pose, barks: ‘Come in and study your books. How many times must I tell you to keep away from those children?’ In this configuration, cinema and dances represented welcome distractions from the work of college life (exams). Importantly, both movies and dances are depicted as of the same generation as the ‘Student Body.’ Both leisure activities are represented as youthful peers as opposed to the overbearing ‘Exam Time’ who hails from another age. ‘The Task Master’ thus depicted college as a series of diversions meant for the young, while exams were a form of drudgery required by adults.

Figure 1.1 ‘The Task Master,’ New York University Daily News, January 10, 1923, p. 4.

In this sense, ‘The Task Master’ speaks to the popular perception of college as a training ground for the twentieth-century American middle class. While over 20 years removed from the first publication of Thorstein Veblen’s The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899), which popularized the terms ‘conspicuous leisure,’ ‘conspicuous waste,’ and ‘conspicuous consumption’ as markers of higher class status in modern society, ‘The Task Master’ depicts the labor enacted by exams as an undesirable ‘subjection to a master,’ while leisure pursuits like movies and dances are represented as the preferred ways to spend one’s time (Veblen, 2009: 28). As Veblen (33) detailed, conspicuous leisure, or the wasteful, ‘non-productive consumption of time’ afforded to those who had the means to be exempt from industrial labor, was one of the primary symbols of elevated status in modernity. According to this definition, college served as a path toward joining the upper ranks as, Veblen noted, higher learning itself began as ‘a leisure-class occupation’ in which study signaled the pecuniary and temporal means for training toward higher class tastes rather than going directly to work (239). However, as a means toward and as a consequence of higher enrollments, the university was undergoing a fundamental shift away from branches of learning, which trained the individual toward leisure-class standards such as ‘traditional “culture,” character, tastes, and ideals,’ toward ‘those of the more matter-of-fact branches which make for civic and industrial efficiency’ (253). For Veblen, this transition signaled the growing middle-class nature of the university in which courses became oriented toward the productive use of time, while extracurricular activities became the primary source of inculcating leisure-class values. He singled out fraternities and athletics as the new rivals of coursework for ‘primacy in leisure-class education’ as both necessitated the types of conspicuous waste (of time and money) valued by the upper and middle classes (246, 257). In this vein, as historian John Thelin discusses (2011: 254), ‘the wild activities associated with undergraduate life,’ including ‘fraternity initiations, weekend parties, homecoming extravaganzas, and football games,’ were not rebellious activities directed against parent culture. Instead, these college leisure pursuits ‘were ultimately conservative because they sealed once and for all the popular belief that “going to college” was a rite of passage into the prestige of the American upper-middle class.’

As Veblen (2009: 50, 60–61) noted for modernity in general, as increasing urbanization and social mobility led to larger communities in which all were not known to each other, conspicuous consumption, or the ‘unproductive consumption of goods,’ began to overtake conspicuous leisure as the primary sign of wealth and status. The 1920s university was no exception, as higher enrollments transformed formerly intimate campuses into mass educational settings where previous class markers became indistinguishable (Thelin, 2011: 205). For Veblen (2009: 59), when ‘lines of demarcation between social classes have grown vague and transient,’ emulation of the leisure-class style of conspicuous consumption became the primary means of class rise. 1920s aspiring big men (and women) on campus, like Lloyd’s Harold Lamb, signaled their desired status through clever college clothes that aimed to highlight their individuality yet still conform to prevailing norms. One example of this is the autographed rain slicker that became synonymous with college youth in the 1920s. The slicker first gained popularity as protection during rainy football contests and then transformed into subcultural reappropriation of a mass-produced item (Ohio State Daily Lantern, 1926). In an antecedent of graffiti, students decorated their slickers with pithy slogans about life, love, and school, including those for fraternities, sororities, and athletic teams, to signal their affinity with these peer-oriented youth organizations. As the practice became widespread, campus-adjacent businesses stepped in to help the collegians conform to this accepted canon of leisure-class style. A month before The Freshman premiered in theaters, the Ohio State Daily Lantern published an advertisement for ‘“Collegiate” slickers’ that offered to provide undergraduates an ‘expression of your own individuality,’ such as a catchphrase or cartoon, free of charge (or for 50 cents if drawn in color), with the purchase of their oilskins (‘“Collegiate” Slickers,’ 1925). In this case, a style that began as an expression of individuality and a refusal of adult norms transformed into a form of conspicuous consumption where those without the time, talent, or imagination to decorate their own slickers could buy a ready-made badge of ‘collegiate’ style.

In the early 1920s, college students’ conspicuous consumption of collegiate style regularly signaled a tension between youthful individuality and conformity as a sign of middle-class status. A November 1924 advertisement for Dexter Clothes ...