eBook - ePub

The Education of Children with Severe Learning Difficulties

Bridging the Gap between Theory and Practice

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Education of Children with Severe Learning Difficulties

Bridging the Gap between Theory and Practice

About this book

First published in 1986. Aimed at teachers, students and related professions this book serves to bridge the gap between the theory and practice of educating pupils with severe learning difficulties. In the light of the 1981 Education Act it is crucial to identify, and subsequently meet, the needs of these pupils. This can only be done by an in-depth understanding of curriculum design, child development and the learning process. This book incorporates these aspects together with an appreciation of teaching techniques and school and classroom organisation. It explains how the parents, school staff and linked agencies complement this procedure.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Education of Children with Severe Learning Difficulties by Judith Coupe,Jill Porter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE: CURRICULUM METHOD AND ORGANISATION

At the heart of any purposeful education lies the curriculum. When it is accompanied by an agreed strategy for assessment, programme planning recording and evaluation, Judith Coupe shows how the school can account for meeting the needs of individual pupils. An effective curriculum should provide guidance for a balanced selection of priority target behaviours and all those experiences and activities which promote the continual development of the whole child.

In this context, Jill Porter in Chapter 2 provides a rationale for the use of a behavioural approach to teaching the child with severe learning difficulties. She emphasises the need to think beyond simple contingency manipulations to the role of errors in learning. Centring on the major problems — that of achieving maintenance and generalisation, she considers the nature of reinforcement and that of stimulus control and setting conditions. Fundamental to the generalisation process is the need to teach discrimination and to build up sequences of behaviour.

Peter Sturmey and Tony Crisp in Chapter 3 cite evidence to show that learning in small groups is possible and may even facilitate learning by imitation — an important learning to learn skill. They discuss the problems of small group teaching, for example, the need for entry requirements to the group, and the tendency for teaching to be on one particular task (usually language, imitation or table-top activities), in addition to the perennial problem of how to provide for the remainder of the class. Guidelines are given for small group teaching. The authors then go on to discuss assigning particular roles to staff and compare this method of classroom management with small group and individual teaching. There is no doubt, in the evidence provided, that assigning roles and small group teaching lead to high levels of activity and compare favourably with traditional one-to-one teaching.

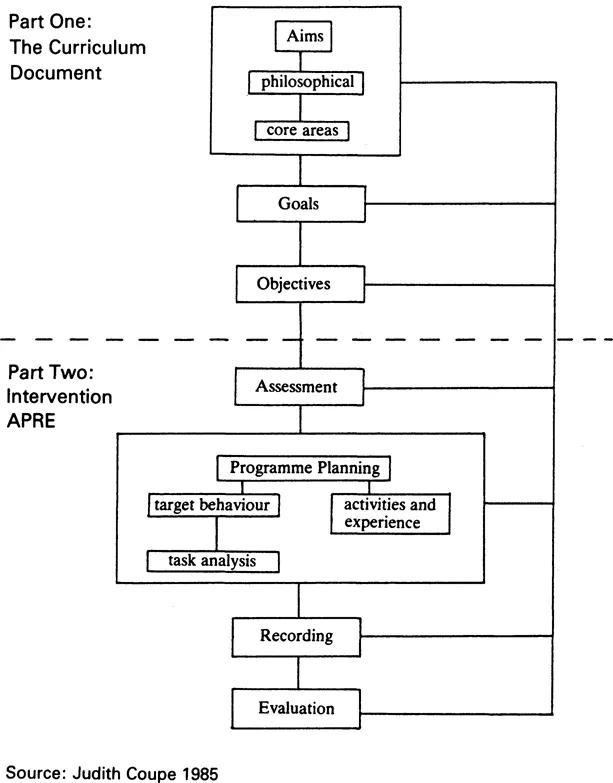

1 THE CURRICULUM INTERVENTION MODEL (CIM)

Introduction

The 1981 Education Act states that all pupils in need of any special educational input are referred to as pupils with special educational needs. Under Section 5, notice of intention to assess is served on parents whose child may have special educational needs. Subsequent assessment is a multi-disciplinary process which requires the advice of the parents, teacher, school medical officer and educational psychologist. The latter three component personnel must be involved, but at the same time other advice may be sought. Advice reports are collated and summarised in the educational statement. Highlighted in this document is the necessity to identify the pupil’s abilities in terms of strengths and weaknesses and to plan for the immediate and long term needs. Obligatory reviews, held at least annually with parents, ensure continual evaluation of these needs and how they are being met. In order to make certain that the prescribed changes are occurring, a monitoring system must be built into the school’s curriculum. In this way an evaluation can be made of whether or not the intended outcomes are, in fact, being obtained. A well-documented objectives curriculum should enable a school to fulfil this requirement to assess, programme plan, record and evaluate.

DES Circular 6/81 refers to the necessity for all schools to produce curriculum statements. Four obligatory areas are identified:

1. each school is to write a statement on what it intends to do for its pupils, i.e. aims;

2. information is to be made available as to how these aims will be achieved;

3. information is to be made available as to how the school will monitor and evaluate its success in achieving what it sets out to do, i.e. curriculum;

4. information is to be made available as to how the school will inform parents, governors, professional colleagues and the community of its philosophy and curriculum emphasis.

It is important for the school to see the value in preparing a structured curriculum document based on an agreed philosophy and methodology. The curriculum is seen as an instrumental device through which the school mobilises and organises its professional and material resources to achieve specified ends. It involves those activities and experiences which are directed by the school or influenced by other societal agencies so that its avowed purposes will be fulfilled. It is a mechanism through which it is hoped to produce continuous and cumulative changes in pupil behaviour which would only emerge at different rates, if at all, in the absence of intervention. It is essentially a means through which planned modifications in pupil behaviour are produced progressively.

Traditionally headteachers have been left with almost total responsibility for planning the curriculum in their schools (Wilson 1981). However, it is increasingly recognised that, alongside the school staff, parents, governors, etc. have a legitimate interest. What is taught must reflect fundamental values in our society and is ‘largely a measure of the dedication and competence of the headteacher and the whole staff and of the interest and support of the governing body’ (Welsh Office, DES 1981). The quality of a pupil’s education is dependent on the expertise of teaching, the resources available and in particular, the curriculum. Ultimately, it is the teacher who ensures that the individual needs of each pupil are met. However, it is the curriculum that provides the direction and relevant information from which these decisions can be made. It needs constantly to be open to evaluation and change.

The Warnock Committee (DES 1978) claimed that staff involvement and commitment are necessary for a curriculum to succeed. Indeed, all staff should have a vested interest in its continuing development, and teachers should feel justified in seeing themselves as a source of expertise. The Warnock Report also stressed that the curriculum will be determined by four interrelated elements: 1. setting of objectives; 2. choice of materials and experiences; 3. choice of teaching and learning methods to attain the objectives; 4. evaluation. In turn, this is sanctioned by the enactment of the 1981 Education Act and Circular 6/81.

Establishing a Framework of Curriculum

A curriculum must never be imposed on a school (DES 1978); staff must have a sincere interest in its development, and their skills must be utilised appropriately. The qualities and skills required from staff will incorporate commitment, motivation, teamwork, communication of ideas, analytical evaluation of self and others and also acceptance of change. Essentially, it is necessary for all staff to work closely together to share ideas, support each other, teach consistently and meet the needs of each individual pupil. In this way curriculum development leads to a consensus of agreement, hence consistency and continuity of teaching. Nine important considerations are expressed by Burman, Farrell, Feiler, Heffernan, Mittler and Reason (1983).

1. The whole school must agree the need to look at curriculum, and parents should be asked about their priorities.

2. The roles of linked agencies need to be clarified in terms of how much commitment they can offer.

3. All staff who will implement the approach need to be included.

4. Once core areas are defined, staff need to organise themselves into groups and decide on the compartments.

5. Decide on the frequency of meetings and target dates for work to be submitted from groups.

6. Identify and agree on the level of skill components so that objectives are sequenced consistently.

7. Try out sequences of objectives regularly and discuss.

8. Discuss and utilise the school’s existing curriculum.

9. Decide when to involve parents:

(a) inform them and explain the new curriculum;

(b) share planning and recording with them;

(c) communicate when targets are realised.

Selecting and developing a particular type of objectives-based curriculum is not a matter of superiority, i.e. one model is not better than another. The main concern is using the strengths of the staff and resources to suit the needs of an individual school in defining what behaviours are considered necessary to teach. Once the objectives-based approach is worked out, it is efficient and simple to run because the teachers know exactly where they are and where they are going. It leads to clear methodology, but at the same time certainly demands a high level of expertise from the teacher (Ainscow and Tweddle 1979). For the benefit of the school and each individual pupil, it is worth all the investment of time and energy so that all pupils can be assessed via precise behavioural objectives. From this, a programme of intervention can be designed for the individual pupil and carried out using target behaviours, task analysis and recording. The school policy on methodology can be incorporated alongside the teacher’s own style and the resulting child performance evaluated.

The objectives framework ensures continuity throughout the school. Access to information is gained easily, and there is a considerable amount of freedom and autonomy for teachers in selecting and implementing programmes. The teacher controls for the success and complexity of individual pupils’ learning. Within the framework of curriculum development it is vital to take a balanced account of all the experiences offered to pupils. To facilitiate the development of attributes such as values and attitudes, curricular activities can be planned deliberately. Yet it is necessary to be aware of the complex nature of these experiences so as to ‘avoid the danger of seeking to measure the unmeasureable’ (Wilson 1981). The essence of curriculum planning should be to achieve purposeful activities whenever teaching takes place. ‘Balance has to be achieved between direct skills teaching and all those other activities which widen horizons, arouse interest and give purpose to learning’ (Wilson, 1981).

Part One: The Curriculum Document

Inspired by its educational aims the curriculum provides a philosophical framework which promotes a sense of purpose to the work of the school. It provides a rationale and a foundation for subsequent goals and objectives. To teach a pupil according to an agreed philosophy, the school will need to produce a curriculum document which provides detailed, structured information which is available to all teachers and which is concerned with what to teach — the ‘what’ of education. This will be developed and continually evaluated and adapted by school staff, parents, governors and all interested agencies. However good this document is, it will be of little use unless, alongside it, the school has identified an agreed procedure of teaching intervention which incorporates assessment, programme planning, recording and evaluation: APRE — the ‘how’ of education. Ainscow (1984) also makes this important distinction between the ‘what’ and ‘how’ of education.

Aims

‘First to enlarge a child’s knowledge, experience and imaginative understanding, and thus his awareness of moral values and capacity for enjoyment; and secondly, to enable him to enter the world after formal education is over as an active participant in society and a responsible contributor to it, capable of achieving as much independence as possible’ (DES 1978).

Aims essentially provide a direction for educational intent. They are concerned with potentialities and possibilities and not concrete behaviours. Plowden (DES, 1967) refers to them as ‘benevolent aspirations’, and Peters (1966) uses the analogy of aims as giving the general direction in which to travel. Educational aims are concerned with what people ought to be, and essentially they should apply to pupils of all ages and abilities in all sectors of education. ‘Aims are also philosophical statements which form a basis of an educational theory. We ask “Why this aim?” and justify the choice by relating it to a philosophy to which we adhere’ (Leeming, Swann, Coupe and Mittler, 1979).

The Cheshire Curriculum Statement (1982) makes it clear that pupils should have the right of access to different areas of human knowledge and experience. Similarly, Manchester LEA (1984) produced aims of schooling based on widely agreed statements of collective purpose:

1. to develop lively, enquiring minds capable of independent thought and the ability to question and argue rationally and to apply themselves to tasks;

2. to acquire the knowledge and skills relevant to adult life and to participate as citizens and parents in a rapidly changing world;

3. to appreciate human achievement and aspiration through the study of major areas of knowledge and experience, including language and literacy, mathematics, art, music, drama, science, technology and physical pursuits, and to experience a sense of achievement in these fields;

4. to acquire reasoned attitudes, values and beliefs including a respect for and understanding of other people’s religious and moral values and ways of life;

5. to understand the world in which they live and the interdependence of individuals, groups and nations;

6. to experience responsibility, develop negotiating s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Part One: Curriculum Method and Organisation

- Part Two: Factors Influencing Learning and Development

- Index