- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Managing the Primary School

About this book

Originally published in 1989. This book, which was one of the first to take account of the recommendations of the Education Reform Act which came into effect in September 1988, provides a practical overview of primary school management from resources, which include staff, space, equipment and finance, to relationships with outside bodies, governors, parents, teachers, children and non-teaching staff.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralCHAPTER 1

Relationships with the Governing Body

Many new heads have had little real contact with a governing body apart from being interviewed by one. It it not surprising therefore that they should feel considerable uncertainty in establishing a relationship with the governors of their new school. What is the role of the governing body? What are its responsibilities? What are its powers? How much should the governors be told? How much should the head try to involve all of the governors in the life of the school?

These are just a few of the questions which new heads face in establishing their relationship with their governing body. One in eight of Weindling and Earley’s (1987) new secondary heads admitted to a lack of preparation in this area of headship. Interestingly, 29 per cent of the LEA officers, who in many cases had opportunities to observe heads in this part of their job, picked out the relationship with governors as an area of headship for which heads were ill-prepared. However, it is not only new heads who find this relationship problematic. Recent legislation has so radically altered the composition, role, responsibilities and power of governing bodies that even experienced heads are finding that they are entering uncharted territory. Nor is it only headteachers who are uncertain. Even before the recent legislative changes Kogan et al. (1984) found that governors themselves were just as uncertain about the part they were expected to play.

After spending the previous three years studying school governing bodies, Maurice Kogan and his team concluded that:

… at the present time school governing bodies are ‘Sleeping Beauties’ still awaiting the kiss of politics.

(Kogan et al., 1984, p.9)

Their conclusion still holds true though Prince Charming is already pursing his lips. It remains to be seen how far the combined effects of the 1986 and 1988 Education Acts manage to rouse school governing bodies from their traditionally reactive role so that they transform themselves into the proactive controllers of the school which the legislation envisages.

Kogan’s study is the only substantial piece of research on this topic carried out within the last twenty years or so; although it pre-dates the recent legislative changes, I shall still be drawing upon his findings and upon his discussion of the issues, supplemented wherever possible by the somewhat scant evidence on the effects of the 1986 Act.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Governing bodies have a history almost as long as that of schooling itself. They have their origins in the boards of trustees that administered the charity schools which preceded the involvement of the state in the provision of schools. The voluntary schools established by the National Society and the British and Foreign School Society were governed by boards of managers, who raised money for the school, employed its staff and generally supervised all aspects of the running of the school. The elementary schools established by the new school boards following the 1870 Education Act also, for the most part, had boards of managers with varying degrees of power to run the school.

The Cross Commission endorsed the system of school management committees in its Final Report of 1888. The Commission saw managers as contributing to the running of the school in such matters as the hiring and firing of teachers and the provision of equipment. In order to discharge these responsibilities managers would need, in addition to a ‘general zeal for education’, both ‘business habits’ and ‘administrative ability’. However, the Commission saw the managers’ role as more extensive than mere administration; managers would also have an influence over the pupils in order to:

… mould their character, and help to make them good and useful members of society.

(Cross Report, 1888)

This would be achieved by visiting the school frequently and for this task the manager would need:

… some amount of education, tact, interest in school work, a sympathy with the teachers and scholars, to which may be added residence in reasonable proximity to the school, together with leisure time during school hours … and it is hardly necessary to say that personal oversight of the religious and moral instruction implies religious character in those who are to exercise it.

(Cross Report, 1888)

It comes as little surprise to learn from Gordon (1974) that managing bodies were almost entirely middle class in their composition. In London he found that 31 per cent came from the ‘leisured classes’, 21 per cent from the churches and 10 per cent from the professions. Elementary schools, whether provided by a school board or a voluntary society, were provided for working class children by the middle class. The teachers who worked in them were drawn largely, like the children they taught, from the working class, and the board of managers was thus an important control mechanism intended to ensure that elementary schooling did nothing which would challenge the existing distribution of power and wealth in Victorian Britain. Whatever the motivation of individual educators, mass public elementary education was never intended by the legislators to threaten the status quo, but rather to reinforce it.

The 1902 Education Act, which established Local Education Authorities, required all but the smallest LEAs to appoint boards of managers for their schools. A number of LEAs appointed managing bodies for groups of elementary schools; in some cases that group comprised all of the elementary schools in the authority, thus retaining close and direct control of the schools in the hands of the LEA itself. Subsequent legislation continued, with only minor changes, the basic pattern of managing bodies which had become established in the nineteenth century.

When the Taylor Committee began its study of managing and governing bodies in 1975 it found that they had evolved over the years to produce:

… a bewildering variety of practice and opinion …

(Taylor Report, 1977)

Their report was greeted by much consternation on the part of the teaching unions, who saw any extension, or revival, of governing bodies’ powers as a threat to the autonomy of heads and teachers. The Committee produced eighty-nine recommendations for the reform of school governing bodies, which were intended to produce a mechanism whereby:

… all the parties concerned for a school’s success – the local education authority, the staff, the parents and the local community – should be brought together so that they can discuss, debate and justify the proposals which any one of them may seek to implement.

(Taylor Report, 1977)

Their intention was reflected in the title of their report: A New Partnership For Our Schools. Every school should have its own governing body composed of representatives drawn equally from the LEA, the staff, the community and the parents. This body would have clearly defined, but wide ranging, powers to control all school policy decisions. The recommendations on membership were controversial at the time not only because they included equal representation for parents but because the LEA would lose its majority on the new, more powerful governing bodies.

The Education Act 1980, which was not fully implemented until 1985, embodied only token versions of the Taylor recommendations. It required all governing bodies to include representatives of both the teaching staff and of the parents. Headteachers were given the right to be governors of their own school if they so chose, but the LEAs were allowed to retain a majority of their own nominees on each governing body. It ended the use of the term ‘managing body’ for primary schools; largely ended the practice of grouping schools under joint governing bodies; insisted that minutes should be open to the public; and limited the number of governing bodies upon which any individual might sit. However, it remained silent upon the subject of the functions and powers of governing bodies.

The Green Paper Parental Influence at School (1984) suggested two major changes in the law relating to school government:

… first that parents elected by their fellow parents in a secret ballot should be able to form the majority on the governing bodies of county and maintained special schools … second, that appropriate powers for governing bodies should be entrenched by legislation so that these could not, as can happen at present, be overridden by the LEA.

(DES, Better Schools, 1985, p.64)

The reaction to the proposal to give parents a majority was so hostile, with even such bodies as the National Confederation of Parent Teacher Associations opposing it, that the subsequent legislation, the Education (No.2) Act 1986, did not include any such provision. It is this Act which provides the current statutory framework for school government – a framework which seeks to limit the power of the LEAs in the control of schools by increasing that of parents and of the community, and which largely eliminates the ‘bewildering variety of practice’ which the Taylor Committee noted.

THE CURRENT POSITION

The current statutory framework for school government is provided by the 1986 Education (No.2) Act and the Education Reform Act 1988. Taken together these measures substantially increase the power of governing bodies, largely at the expense of the LEA rather than of the head.

i Composition of the governing body

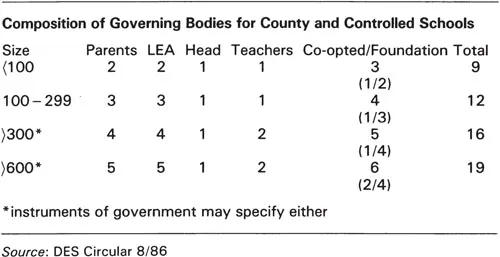

The composition of the governing body of each school is intended to ensure that ‘… no single interest will predominate’ (Better Schools, DES, 1985). Thus none of the partners (LEA, staff, parents, community) has a majority on the governing body. Additionally the annual meeting of parents is intended to strengthen the parents’ influence on the governors. The composition of governing bodies is given in the table.

ii Governors and the curriculum

The 1986 Act gave significantly greater responsibilities to the governing body for determining the curriculum, but these have been modified and reduced by the 1988 Act. The establishment of a National Curriculum reduces the scope for governors to participate in the decision-making concerning what should be taught in the school. The LEA is required to determine its policy for the secular curriculum in all the schools which it maintains and this policy must include all the statutory elements of the National Curriculum. The governing body of each school must define the secular curriculum for the school in the light of the LEA’s policy and the requirements of the National Curriculum. In doing this the governors must consult the headteacher and the LEA if they propose to modify the LEA’s policy. The head is then required to implement the governors’ curriculum policy in the school. The governors have a responsibility to ensure that the National Curriculum is followed. Whether sex education is to be included in the school’s curriculum is to be determined by the governing body, but where it is they must ensure that it encourages ‘… the pupils to have due regard to moral considerations and the value of family life’. The governors also share with the head and the LEA a responsibility for ensuring that the ‘junior pupils’ do not engage in any partisan political activities in school and that no teachers promote partisan political views in their teaching. These provisions were the result of amendments during the passage of the 1986 Act and their interpretation has yet to be defined by the courts; until that happens their precise meaning is by no means easy to see. Nor is it easy to see exactly how governing bodies will use their power to modify the LEA’s curriculum policy, but the requirement to follow the National Curriculum leaves little room for local variation, which was of course the Secretary of State’s intention. It seems likely that governors will in practice do little more than discuss the relative time allocations to different subjects within the National Curriculum. The arrangements for te...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword by Professor Peter Robinson

- Introduction

- 1 Relationships with the Governing Body

- 2 Relationships with Parents

- 3 Relationships with the LEA

- 4 Relationships with the DES: the Role of HMI

- 5 The Effective Headteacher

- 6 Managing One’s Own Time

- 7 Managing the Curriculum

- 8 Managing Financial Resources

- 9 Managing Change

- 10 Managing for Continuity

- 11 Evaluating and Developing the Work of the School

- 12 Staff Selection and Appointment

- 13 Staff Development

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Managing the Primary School by Tim Hill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.