![]()

Experiences applying the climate resilience framework: linking theory with practice

Marcus Moench

This paper discusses the evolution and application of the Climate Resilience Framework (CRF). The framework focuses on the roles of systems, agents, institutions, and exposure in climate resilience and adaptation, and supports planning and strategic policy development using iterative shared learning techniques. Conceptual foundations of the CRF are explored, along with its application in a range of implementation and research contexts, including: urban planning (Asia), food systems (Nepal, Central America), and post-flood recovery (Pakistan, USA). These illustrate how analysis of system dynamics and agent behaviour in different institutional contexts can be used to identify points of entry for building resilience.

Cet article traite de l’évolution et de l’application du Cadre de résilience au changement climatique (Climate Resilience Framework – CRF). Ce cadre se concentre sur les rôles des systèmes, agents et institutions et sur l’exposition dans la résilience et l’adaptation au changement climatique, et il soutient la planification et l’élaboration de politiques stratégiques au moyen de techniques d’apprentissage itératives communes. Les fondations conceptuelles du CRF sont examinées, ainsi que son application dans une variété de contextes de mise en œuvre et de recherche, y compris : la planification urbaine (Asie), les systèmes alimentaires (Népal, Amérique centrale) et le relèvement post-inondations (Pakistan, États-Unis). Ces contextes illustrent comment l’analyse de la dynamique des systèmes et du comportement des agents dans différents contextes institutionnels peut être utilisée pour identifier des points d’entrées afin de renforcer la résilience.

El presente artículo examina la aplicación y la evolución seguida por el Marco de Resiliencia Climática (CRF). Mediante el uso de técnicas iterativas de aprendizaje compartido, este marco, que opera como un auxiliar para la planificación y el desarrollo de políticas estratégicas, se centra en los roles de los sistemas, los agentes, las instituciones y la experiencia en el ámbito de la resiliencia y de la adaptación al clima. Asimismo, el artículo examina los fundamentos conceptuales del CRF y sus aplicaciones en numerosos contextos de implementación y de investigación, entre los cuales se incluyen la planificación urbana (Asia), los sistemas alimentarios (Nepal, Centroamérica), y la recuperación posinundaciones (Pakistán, EE. UU.). Tales contextos ilustran cómo el análisis de dinámicas de sistema y el comportamiento de los agentes en distintos entornos institucionales pueden ser utilizados para identificar temas de abordaje a través de los cuales ir construyendo la resiliencia.

A framework for understanding climate resilience

Resilience, the ability to bounce back and withstand disruption, is increasingly at the centre of debates over development and responses to climate change. The Resilience Alliance defines the resilience of a social-ecological system (SES) as: “the ability to absorb disturbances, to be changed and then to re-organise and still have the same identity (retain the same basic structure and ways of functioning)” (Resilience Alliance 2014). This definition resonates strongly with the challenges of an increasingly interconnected world where climate and other change processes threaten development progress and tensions exist between change and continuity. Like all high-level concepts however, translating resilience into practice requires frameworks that relate basic scientific understanding of SES dynamics to much more specific factors.

The framework developed through work by ISET and numerous other partners for understanding climate resilience has been outlined in recent work through the Asian Cities Climate Change Resilience Network (ACCCRN) (Tyler and Moench 2012; Moench, Tyler, and Lage 2011). Although this focuses on urban areas, the framework was developed on the basis of a much wider array of theoretical and applied research over several decades mostly, though not exclusively, in South Asia.

Elements of the framework emerged initially in debates over integrated water resources management (IWRM). While the importance of integrated understanding in managing any complex system is fully acknowledged, we found that attempts to integrate numerous and often fundamentally different considerations into a single overview perspective often obscured key factors (Moench, Caspari, and Dixit 1999; Moench et al. 2003). In the IWRM case, most applied work focuses on high-level basin management agencies attempting to address competing needs within a river basin. In comparison to prior sector-focused approaches to water management this represented a major advance. In practice, however, IWRM was often framed as a command and control strategy for optimal allocation of available supplies that ignored the diverse array of actors, institutions, and often very localised system characteristics that determine water use and allocation. It involved attempts to reduce variability in ways that ultimately increased system rigidity and the consequences of failure – what Holling and Meffe (1996, 328) call “the pathology of natural resource management”. Furthermore, our field research often identified emergent water outcomes that could not be planned based on high-level analysis. They reflected interactions between a wide array of actors and system components and were often full of surprises and unanticipated interactions at local levels and across scales (Moench et al. 2003).

Although initially identified in work on water resources, very similar issues are common in our more recent work on urbanisation, food systems, and disaster risk management. Urban systems are widely recognised as combining a diverse array of interacting human and physical (infrastructure and ecological) elements (Pickett et al. 2001; Alberti et al. 2008). This is also the case with disaster risk (Wisner et al. 2004) and food systems (Ericksen 2007; Ericksen, Ingram, and Liverman 2009). So far, however, attempts to successfully integrate analysis and incorporate results in response processes have had limited success. As a result, broad streams of research on complex systems now emphasise the local contextual factors that contribute to emergent patterns of vulnerability and resilience.

Overall, integrated framing can de-emphasise the role of specific system components, the incentives driving actors, and the formal and informal institutional arrangements that bound behaviour. As a result, attempts to develop fully integrated perspectives can obscure as much as they reveal. Furthermore, attempts at integration often lead to command-and-control or predict-and-prevent recommendations with the expectation that these can be implemented in a top-down manner. Attempts often fail, however, because they de-emphasise the complex factors at play in local contexts and the interests and behavioural drivers of local communities, the private sector, and local government actors. Most attempts at integration are not designed with specific processes to deeply engage actors, understand the nuances inherent in local contexts, and support learning and the inevitable need to adjust course. The focus is often on integration rather than the need for inclusive and adaptive process to build ownership, encourage learning, and support change as conditions evolve.

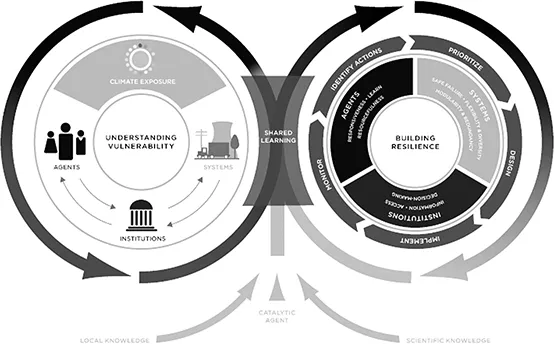

Given the above, we structured the CRF as both an analytical framework designed to encourage insights across system-agent-institutional boundaries, and as an iterative planning process where shared learning would build understanding and encourage adaptive responses (Figure 1). Rather than integration, the goal is to support ownership, recognition, and response as conditions evolve and knowledge grows. It is designed for emergent needs rather than integrated prediction and response.

The two circles represent an iterative flow of shared learning through analysis and action to build resilience. The left side describes a vulnerability diagnostic phase, while the right side focuses on the steps that can be taken. The process involves analysis followed by identification of context-specific actions, prioritisation, design, implementation, and monitoring before returning to the basic diagnosis. It was structured to respond to the needs of planning organisations and could be changed for other uses. This paper focuses is on the characteristics of systems, agents, and institutions that contribute to resilience, rather than the process; consequently, it focuses on the diagnostic aspect. It is important to emphasise, however, that iterative processes for building understanding, engaging different groups of agents, and adapting approaches are central to resilience and are fundamental to the CRF.

The resilience diagnosis reflects basic distinctions between the characteristics of physical systems, agents, institutions, that determine their resilience when exposed to disruption. These distinctions reflect the fact that social-ecological systems (SES) are composed of physical elements, the human individuals and organisations that manage or use them, and the institutional “rules in use” that structure behaviour. Each element reacts differently to stress and the resilience of each contributes to resilience of the SES as a whole. Resilience as an outcome – the overall ability of the SES to spring back or evolve – is an emergent property that reflects characteristics of the components and the stresses they are exposed to.

Figure 1. Climate Resilience Framework.

Source: Friend and MacClune 2012, adapted from Moench, Tyler, and Lage 2011.

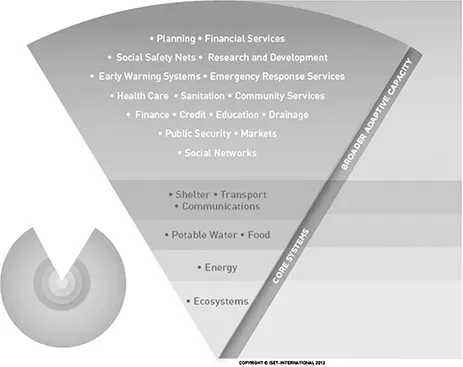

When subject to the sudden-onset types of disruption anticipated as a consequence of climate change, relationships within SES are structured hierarchically (Figure 2). High-level systems, such as markets, social networks, and organisations depend in fundamental ways on underpinning communications, transport, shelter, finance, water supply, and other infrastructure. These systems depend, in turn, on even more basic energy and environmental infrastructure. Without power, communications, transport, and many shelter systems do not function; without communications and transport, organisations, markets, financial systems, and social networks cease to function. As a result, when subject to sharp sudden-onset, hydro-meteorological events, some of the largest potential for cascades is outward from critical ecological and infrastructure systems to the diverse forms of social organisation they support (although the reverse is likely to be true with social forms of disruption such as war). At the same time, however, the ability to respond to system failures, to maintain systems and to adjust as conditions evolve resides in the agents and institutions at higher levels. These higher-level elements are the main source of creativity and adaptive capacity. As a result, resilience of an SES as a whole depends on the characteristics of the core systems, the capacities of agents and organisations at higher levels, and on the institutional features that mediate the interactions between systems and agents.

Systems

Where physical infrastructure or ecosystems are concerned, characteristics that have been widely documented as contributing to resilience include: flexibility and diversity, redundancy and modularity, and safe failure (Tyler and Moench 2012). These aggregate characteristics reflect a number of underlying attributes. Multiple pathways for service provision, the ability to reconfigure key elements to serve multiple functions, locational distribution, and reliance on interchangeable units all contribute (O’Rourke 2007).

Figure 2. Systems Diagram.

Source: Adapted from Moench, Tyler, and Lage 2011.

These characteristics have practical implications. In a water supply system for example, diverse surface and groundwater supplies, a diversified piping network, and independently powered pumping units reduce the risk that failures will disrupt service provision. At the same time, however, the density of systems and interdependencies between them can undermine resilience even when first-order conditions are met. Water systems, for example, depend heavily on power supply and failures in either system can cascade across both either directly or through physical proximity (O’Rourke 2007). Resilience also often depends on the nature of the disruption. An energy system that, for example, has all the characteristics of flexibility, diversity, redundancy, modularity, and safe failure in relation to hydro-meteorological events may not have those characteristics in relation to fuel availability or economics. As a result, system characteristics must be evaluated in relation to potential sources of disruption. Resilient to what is often a key question.

Beyond the characteristics of individual systems, the resilience of regions often depends on the resilience of the underlying support systems. The ability of people and organisations to respond effectively following disaster, for example, depends on whether or not they can access key services. Communication, mobility, power supply, food, and water are basic requirements. Services provided by these systems in turn enable different forms of social organisation and interaction – from hierarchically structured governmental organisations to markets, social networks, and mass movements. When critical systems and the services they provide are disrupted by extreme climatic or other events, this disrupts the functioning of most forms of social organisation. Over longer time periods, however, the reverse is often true. The nature and condition of physical systems depends heavily on how they are managed, maintained, and in some cases designed by individuals and organisations.

The physical factors contributing to resilience in systems are probably better understood than those contributing to agent capacities and shaping institutions. As a result, the following discussion of agents and institutions explores capacities and institutional characteristics in greater depth than the systems characteristics above.

Agents

Where agents are concerned, critical capacities can be summarised as the ability to learn, resourcefulness, and responsiveness (Tyler and Moench 2012). Each characteristic has a range of features that contribute to their resilience function.

Ability to learn

Learning is of fundamental importance if agents are to change strategies as climate evolves. Numerous factors, however, influence the ability of individuals and organisations...