- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Camera-Aided Robot Calibration

About this book

Robot calibration is the process of enhancing the accuracy of a robot by modifying its control software. This book provides a comprehensive treatment of the theory and implementation of robot calibration using computer vision technology. It is the only book to cover the entire process of vision-based robot calibration, including kinematic modeling, camera calibration, pose measurement, error parameter identification, and compensation.

The book starts with an overview of available techniques for robot calibration, with an emphasis on vision-based techniques. It then describes various robot-camera systems. Since cameras are used as major measuring devices, camera calibration techniques are reviewed.

Camera-Aided Robot Calibration studies the properties of kinematic modeling techniques that are suitable for robot calibration. It summarizes the well-known Denavit-Hartenberg (D-H) modeling convention and indicates the drawbacks of the D-H model for robot calibration. The book develops the Complete and Parametrically Continuous (CPC) model and the modified CPC model, that overcome the D-H model singularities. The error models based on these robot kinematic modeling conventions are presented.

No other book available addresses the important, practical issue of hand/eye calibration. This book summarizes current research developments and demonstrates the pros and cons of various approaches in this area. The book discusses in detail the final stage of robot calibration - accuracy compensation - using the identified kinematic error parameters. It offers accuracy compensation algorithms, including the intuitive task-point redefinition and inverse-Jacobian algorithms and more advanced algorithms based on optimal control theory, which are particularly attractive for highly redundant manipulators.

Camera-Aided Robot Calibration defines performance indices that are designed for off-line, optimal selection of measurement configurations. It then describes three approaches: closed-form, gradient-based, and statistical optimization. The included case study presents experimental results that were obtained by calibrating common industrial robots. Different stages of operation are detailed, illustrating the applicability of the suggested techniques for robot calibration. Appendices provide readers with preliminary materials for easier comprehension of the subject matter. Camera-Aided Robot Calibration is a must-have reference for researchers and practicing engineers-the only one with all the information!

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

OVERVIEW OF ROBOT CALIBRATION

I. THE MOTIVATION

Robot Calibration is the process of enhancing the accuracy of a robot manipulator through modification of the robot control software. Humble as the name “calibration” may sound, it encompasses four distinct actions, none of which is trivial:

Step 1: | Determination of a mathematical model that represents the robot geometry and its motion (Kinematic modeling). |

Step 2: | Measurement of the position and orientation of the robot end-effector in world coordinates (Pose Measurement). |

Step 3: | Identification of the relationship between joint angles and end-point positions (Kinematic Identification). |

Step 4: | Modification of control commands to allow a successful completion of a programmed task (Kinematic Compensation). |

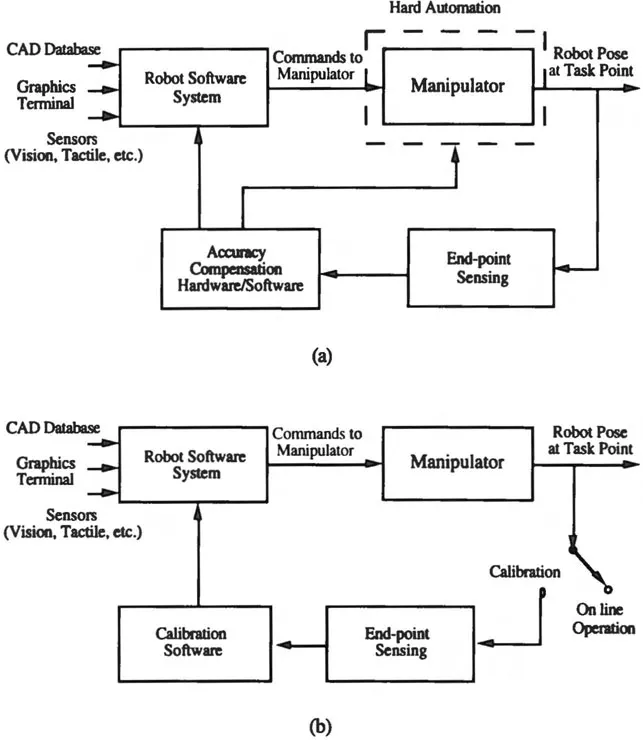

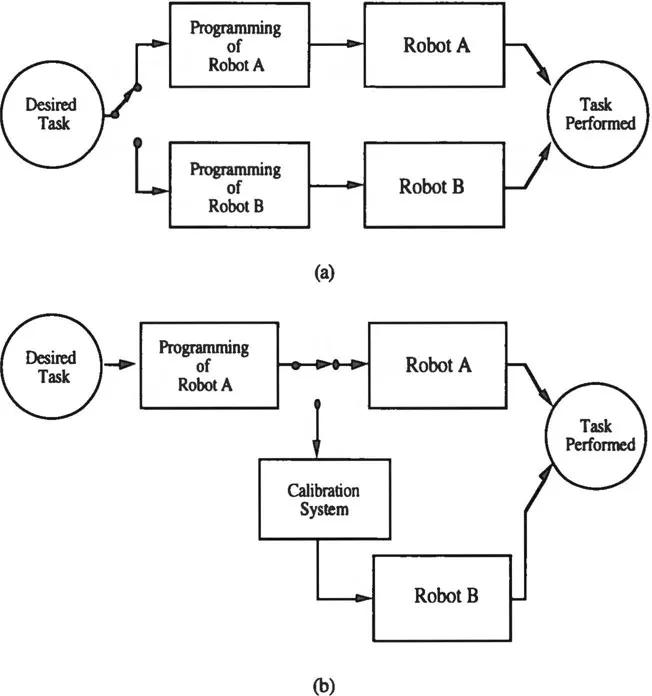

The need for robot calibration arises in many applications that necessitate off-line programming and situations that require multiple robots to share the same application software. Examples of the first are assembly operations, in which costly hard-automation (such as the use of accurate x-y positioners for the assembly part) to compensate for robot inaccuracies may be avoided through the use of calibration, as shown in Figure 1.1.1. An example of the latter is robot replacement, where calibration is an alternative to robot reprogramming, as shown in Figure 1.1.2.

Without calibration, robots which share application programs may experience significant accuracy degradation. The need to reprogram the machine upon replacement (or upon other maintenance actions that may cause permanent changes in the machine geometry) may result in a significant process down-time. Robots should be calibrated in a time period which is a fraction of the reprogramming time for calibration to be economically justifiable.

The growing importance of robot calibration as a research area has been evidenced by a large number of publications in recent years, including books and survey papers. Readers interested in surveys of robot calibration and detailed reference lists are referred to the book by Mooring, Roth, and Driels (1991) and a survey paper by Hollerbach (1988).

This book is not intended to be one more comprehensive survey of calibration. It focuses on camera-based techniques for robot calibration utilizing a unified modeling formalism developed and refined by us over recent years. We naturally chose to put main emphasis on our own research results; but, of course, these results were not developed in “empty space”, as will be shown in the next section.

Figure 1.1.1. Assembly Operations: (a) Without robot calibration (b) With robot calibration

Figure 1.1.2. Robot replacement: (a) Individual programming of each robot (b) With calibration

II. HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

The following brief historical review of Robot Calibration research and practice portrays our own subjective view of key references and achievements that were most related to our own work and have had the biggest influence on us.

The booming growth of Robotics research in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s was a direct result of successful application of robot manipulators to automated manufacturing, particularly in the automotive industry and parallel to that the rapid growth in the computer industry. The predominant method of robot programming, suitable for the applications at that time, was “Teaching by Doing”; that is, physically moving the manipulator to each task point, recording and later replaying the joint-space description at these joints. Manipulators were designed to be highly repeatable and most applications involved a relatively low number of task points with minimal interaction between the robot and external sensors.

Richard Paul’s book (1981) has been a major influence on all robotics researchers of the 1980’s. His systematic use of homogeneous transformations and the Denavit-Hartenberg (D-H) mechanism kinematic modeling formulation for robot path planning and control quickly became universal standards. Many manipulator controllers were subsequently built featuring D-H forward and inverse models. The theoretical tractability of Task-Space robot path planning and the advent of sophisticated sensors such as solid state cameras, force sensors, and various types of proximity sensors and the personal computer revolution all fueled the high expectations that robot manipulators would be soon used to implement fully automated “factories of the future”, and be key elements in many sophisticated multi-step applications involving task-space description and on-line interaction with large magnitudes of sensory data.

Such applications require, in principle, repeated use of the robot inverse kinematic model. In addition there is a need to program the robots off-line to move to task points never visited before by the robot. Such off-line programmed robots must be designed not only to be repeatable but, more importantly, to be accurate. The accuracy of a manipulator depends strongly on the accuracy of the robot geometric model implanted within its controller software. Robotics researchers and practitioners from academia and industry began to study the effects of joint offsets, joint axis misalignment and other accuracy error sources on the manipulator end-effector position and orientation errors.

The first major discovery, found independently by Mooring (1983) and Hayati (1983), which in retrospect established Robot Calibration as a new research area, was that the D-H model is singular for robots that possess parallel joint axes. More specifically, the common normal and offset distance parameters may undergo large changes when consecutive joint axes change from parallel to almost-parallel. Both researchers offered alternative robot kinematic models: Hayati introduced a modification to the D-H model which gained popularity and was subsequently adopted by many other researchers. Mooring advocated a model introduced earlier in the mechanism kinematics literature (for instance, refer to Suh and Radcliffe (1978)) based on the classical Rodrigues equation. Since most industrial manipulators are designed to be “simple”, that is, to have parallel or perpendicular consecutive joint axes, this singularity problem is a major issue from a practical view point.

During the 1980’s many robot calibration researchers came with their own model versions. In fact, the number of models almost equaled the number of researchers. An excellent survey of this flood of models, categorized into 4-, 5- and 6-link parameters models is Hollerbach’s paper (1988). The survey concluded with the following comment:

One issue that should be settled in the future is the choice of coordinate system representation. One strong alternative seems to be the Hayati modification of the Denavit-Hartenberg representation. It is not clear at this point what advantage the six-parameter representations would have for modeling lower-order kinematic pairs, while they have the disadvantage of redundancy.

To be able to improve the accuracy of the robot one needs to be able to measure the world coordinates of the robot end-effector at different robot joint-space configurations and record the joint positions at such configurations. If end-effector position and orientation, as predicted by the robot nominal forward kinematic model by plugging in the joint readings at the selected measurement configurations, differ from the actual end-effector pose measurement, the robot model needs to be suitably adjusted. That is what Robot Calibration is all about.

From a data collection point of view Robot Calibration is not different from Robot Performance Evaluation (in particular for assessing repeatability and accuracy). Much work on evaluation of machine tools and robot manipulators was performed during the 1980’s at the National Bureau of Standards and one excellent review compiling many such testing techniques is the book chapter by Lau, Dagalakis and Myers (1988). Another beautiful survey of robot end-joint sensing techniques is the paper by Jiang, Black, and Duraisamy (1988). One of the first major reports of actual robot calibration experiments was the paper by Whitney, Lozinsky and Rourke (1986). Data collection was performed by Whitney and his co-investigators using theodolites.

Many Calibration or Robot Testing studies during the 1980’s were done using a variety of measurement techniques ranging from expensive Coordinate Measuring Machines (CMM) and Tracking Laser Interferometer Systems to ones that employed inexpensive customized fixtures. The “heart of the matter” is the measurement in “world coordinates” of one point on the robot end-effector. World coordinates are often defined by the calibration measurement equipment itself. The measured point represents the end-effector position. The measuring of the coordinates of three or more non-colinear end-effector points provides the full pose (position and orientation) of the end-effector. Some measurement devices are capable of measuring the full 6-dimensional pose, some can measure only the 3D position and others, such as single theodolite, measure even less than that.

A major contribution to the Kinematic Identification phase of Robot Calibration was the paper by Wu (1984) in which the Identification Jacobian, a matrix relating end-effector pose errors to robot kinematic parameters errors, is systematically derived. This mathematical tool is very useful for both machine accuracy analysis and machine calibration. Another contribution by Wu and his co-authors was the paper (Veitschegger and Wu (1988)) that introduced two techniques for Accuracy Compensation.

Casting the full robot calibration problem as a four-step problem – modeling, measurement, identification and compensation, was featured in the survey paper by Roth, Mooring and Ravani (1987) and expanded into a full scope book (Mooring, Roth and Driels (1991)). That book was indeed a comprehensive survey of all phases of manipulator calibration as evidenced from research done mostly during the 1980’s. The book is a simply written tutorial to many of the fundamental concepts and methods and is highly recommended for first-time robot calibration practitioners.

In addition to Hollerbach’s “standing question” regarding calibration models, many other open research issues have lingered, such as:

1. What is the relative importance of robot geometric errors compared to non-geometric errors?

2. How is the calibration quality related to the resolution and accuracy of the calibration instrumentation and the method of calibration?

3. How should robot measurement configurations be optimally chosen?

4. How is observability of robot kinematic error parameters related to the selection of calibration configurations and method?

Some of these problems, even today, are not yet fully answered. Practical implementation questions were even more acute:

1. How can robot calibration be done “fast” and “cheap”?

2. Should calibration be done primarily by the robot manufacturer or can the calibration load be shifted to the robot user?

3. Should robots be designed differently from a hardware and software point of view to accommodate on-line calibration capability?

4. What current technology will make robot calibration, performed “on the manufacturing floor”, economically feasible?

Starting with some of the research issues, we believe that our Complete and Parametrically Continuous (CPC) type models, as introduced in the thesis by Zhuang (1989), the paper by Zhuang, Roth and Hamano (1992) and explained in detail in this book, are a step forward toward answering Hollerbach’s question. The CPC model was inspired by a paper by Roberts (1988) in the Computer Vision literature, which discussed a very useful line representation with respect to a local coordinate frame using the directional cosines of the line. In the case of robot modeling a joint axis directional vector is represented in terms of a coordinate frame located on the previous joint axis. The CPC model is a natural evolution of Hayati’s model (1983), Mooring and Tang’s model (1984) and Sheth and Vicker’s model (1972). Hayati’s model utilizes a plane perpendicular to one of the joint axes. Mooring’s model also represented joint axes, however with respect to the world frame. Sheth and Vicker introduced the concepts of Motion and Shape Matrices. Readers are also referred to Broderick and Cipra (1988).

Important observability issues of kinematic error parameters can be addressed through a generic link-by-link error model, originally introduced by Everett and Suryohadiprojo (1988). These are explained in detail in this book.

The CPC models and error-models apply uniformly to manipulator internal links as well as the BASE and TOOL transformation. This makes the model highly convenient to robot partial calibration. Ideas of progressive calibration – starting from BASE only through BASE and joint offsets only, to full scale calibration, were first pursued by Mooring and Padavala (1989).

It is important to fully recognize that the kinematic identification and accuracy compensation processes are merely least squares fittings of a suitable number of design parameters to improve on the overall accuracy. Calibration can be done with any number of available design parameters depending on the actual physical set up. Some robot software systems do not allow the user access to all the coefficients of the robot kinematic model. For instance, in some commercial SCARA arms a user is allowed to modify only the joint variable offsets and the link length parameters. In this light the question about relative importance of non-geometric errors may not be fully meaningful as the least squares fitting is done based on noisy data affected by both geometric and nongeometric sources.

Breaking robot calibration into different levels and focusing on specific partial calibration problems such as Hand-Eye Coordination and Robot Localization is one of the central themes of this book.

With regard to the implementation issues, the “fast and cheap” guideline automatically rules out expensive instrumentation such as Laser Tracking Systems or methods that are highly invasive such as placing contract calibration fixtures within cluttered and application dependent robot work environments. From a calibration cost viewpoint the use of cameras and vision systems is extremely beneficial as these already exist as integral components of most industrial robotic cells. For instance, electronic assembly operations often require the use of a multiple camera setup, one that is attached to the robot end-effector which monitors “fiducial” points on the circuit boards and transmits data which are used to finely adjust the end-effector location and another that may be located within the conveyor system monitoring from below the relative alignment between the robot and the assembly area. Hence, calibration implementation may involve, at most, additional camera calibration boards and specialized calibration software at a cost which is a tiny fraction of the total robotic cell cost. Data acquisition systems using cameras are non-invasive, very fast (potentially) and, in principle there is no increase in the level of difficulty in monitoring more than one point on the robot. In other words, full pose measuring ability is easily feasible.

The major stumbling block that prevented widespread use of cameras for machine tool and robot metrology has been camera resolution, most importantly image sampling due to nonzero pixel size. It can be shown, for instance, that with typ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- 1. OVERVIEW OF ROBOT CALIBRATION

- 2. CAMERA CALIBRATION TECHNIQUES

- 3. KINEMATIC MODELING FOR ROBOT CALIBRATION

- 4. POSE MEASUREMENT WITH CAMERAS

- 5. ERROR-MODEL-BASED KINEMATIC IDENTIFICATION

- 6. KINEMATIC IDENTIFICATION: LINEAR SOLUTION APPROACHES

- 7. SIMULTANEOUS CALIBRATION OF A ROBOT AND A HAND-MOUNTED CAMERA

- 8. ROBOTIC HAND/EYE CALIBRATION

- 9. ROBOTIC BASE CALIBRATION

- 10. SIMULTANEOUS CALIBRATION OF ROBOTIC BASE AND TOOL

- 11. ROBOT ACCURACY COMPENSATION

- 12. SELECTION OF ROBOT MEASUREMENT CONFIGURATIONS

- 13. PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS AND CASE STUDIES

- REFERENCES

- APPENDICES

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Camera-Aided Robot Calibration by Hangi Zhuang,Zvi S. Roth in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Mathematics General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.