Brief Overview

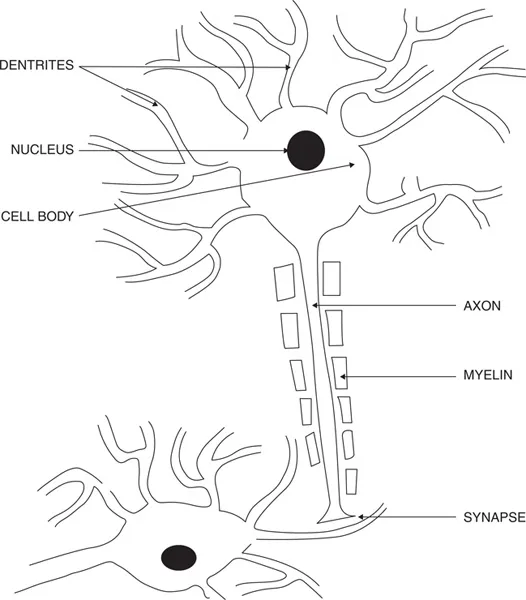

The brain contains millions of cells called neurons (Figure 1.1). These neurons usually have three major divisions: the cell body, the axon, and the dendrites. The cell body is the metabolic center of the neuron, supplying energy to the entire neuron. The dendrites are small branches of the neuron that emanate from the cell body, and the axon is like a long tail. The dendrites from one neuron meet with dendrites from other neurons that are close neighbors. In contrast, the long axons of neurons meet the dendrites or axons of other neurons that are distant. The meeting place between neurons is called a synapse (Figure 1.1). Neurons build up electric charges, and when they are activated, they discharge and send these electrical charges down the dendrites and axons like an electrical cable. When the current reaches the end of these branches, where they meet the ends of other neurons (synapses), they give off chemicals called neurotransmitters. The chemical neurotransmitters can either help to activate/excite the neuron that they are meeting at the synapse or they can inhibit this neuron. When they excite a neuron, they can cause this neuron to discharge (fire) or make it more likely to fire. Alternatively, they can inhibit this neuron from firing.

Figure 1.1 Neuron and synapse. This figure illustrates the dendrites, axons, cell body, and a synapse. The nerve cell or neuron has three major components: the cell body, the dendrites, and the axon. The cell body of the neuron contains the apparatus for producing energy from the oxygen and glucose it receives from the blood. This energy is important to keep an electrical charge across the cell membrane by moving electrolytes across the membrane. The nucleus contains the DNA that is important for the production of proteins. The dendrites are like branches of a tree that meet other neurons and communicate with these neurons. The axon is like a long branch of a tree that also communicates with other neurons. The place where a neuron meets another neuron or muscle is called a synapse. At the end of the neuron, there are chemicals that are given off when the neuron fires and can either excite or inhibit the neuron which the dendrite or axon meets.

There are many different estimates of the number of neurons in the brain, and these range from about 20 to 80 billion. It has been estimated that there are more than 100 trillion connections between these neurons. Not all neurons are connected to each other, but when neurons are connected, they form a network, and different networks in the human brain perform different functions. Some of these networks store information. Others analyze incoming sensory information as well as program movements. There are other neuronal networks that monitor our body, such as our oxygen and glucose levels, as well as other networks that help control organs of our body, such as the heart.

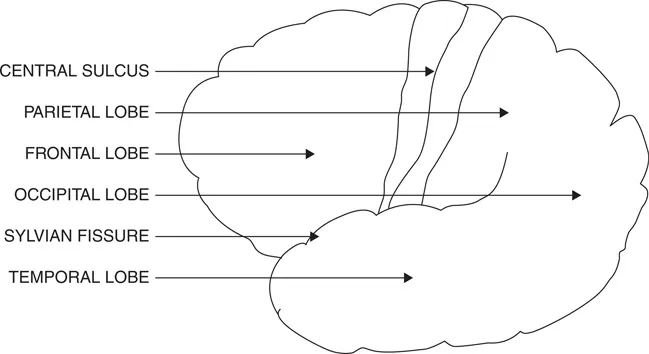

In humans, most of the neurons are on the surface of the brain, and these neurons help form the cerebral cortex. The brain’s cerebral cortex is divided into two hemispheres: one hemisphere on the right and the other on the left. Each hemisphere is divided into four major sections or lobes, including the frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Major lobes of the brain. Image of the left hemisphere as seen from the left side. Each hemisphere contains four major lobes. In the front is the frontal lobe, and in the back is the occipital lobe. Between these lobes on the bottom is the temporal lobe, and above the back part of the temporal lobe is the parietal lobe. The frontal lobe is separated from the parietal lobe by the central sulcus, and the temporal lobe is separated from the parietal and frontal lobes by the Sylvian fissure.

Sensory Cortex and Sensory Association Areas

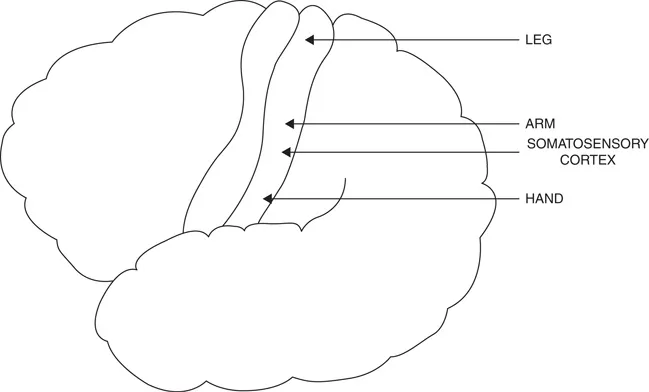

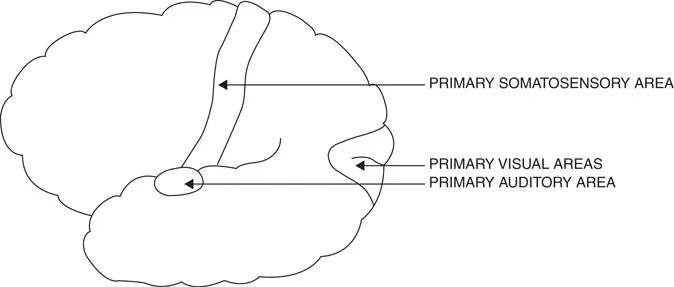

The cerebral cortex receives sensory information in areas called primary sensory cortex. Visual stimuli come to the occipital cortex, at the back of the brain (Figure 1.2). Touch, temperature, pain, and joint position come to the somatosensory cortex, which is in the most anterior (front) portion of the parietal lobe (Figure 1.3). The primary auditory cortex is at the very top of the temporal lobe (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.3 Somatosensory cortex. The somatosensory cortex is directly behind the central sulcus that separates the frontal and parietal lobes. This area is also called the postcentral gyrus. It receives sensory information from the skin (e.g., touch, temperature) and joints (position sense). Injury to this area impairs patients’ ability to recognize objects that they touch as well as the direction and magnitude of joint movements. The lowest part of the postcentral gyrus obtains information from the face and hand, and the highest part obtains information from the lower extremity. This information is transmitted through a relay station deep in each hemisphere called the thalamus.

Each of these primary areas performs an analysis of the incoming information. For example, when sounds come into the ear, they are changed to electrical signals and sent to the primary auditory cortex. The primary auditory cortex determines these sounds’ frequencies (pitch), amplitudes (loudness), and durations. Similarly, with vision, each half of the retina goes to the primary visual cortex in the occipital lobe that is on the same side, and since each half of the retina detects light coming in from the opposite side, the left primary visual in the occipital lobe area detects stimuli in the right side of space, and the right primary visual area detects stimuli in the left side of space. The primary visual cortex then determines the location, orientation, size (e.g., length), color, and movement of visual stimuli. The somatosensory cortex performs a similar analysis for stimuli that touch the skin as well as joints and muscle movements. Sensations from the left side of the body go to the right hemisphere’s somatosensory cortex, and those from the right side of the body go to the left hemisphere. Sensations from different parts of the body go to different portions of the somatosensory cortex (Figure 1.3), with the face and hand being the lowest and the foot and leg being the highest.

Figure 1.4 The primary visual, somatosensory, and auditory areas. Sensory information from the eyes, ears, and skin are all relayed through the thalamus to portions of the cerebral cortex called primary sensory areas. For vision, this area is in the occipital cortex. The tactile information goes to the somatosensory cortex and auditory information to the top of the temporal lobe in an area called Heschl’s gyrus. These primary sensory areas primarily perform an analysis of incoming sensory information. For example, when listening to a person speak, Heschl’s gyrus will analyze the amplitude, duration, and frequency of incoming information but not recognize the meaning of sequence of phonemes that compose words.

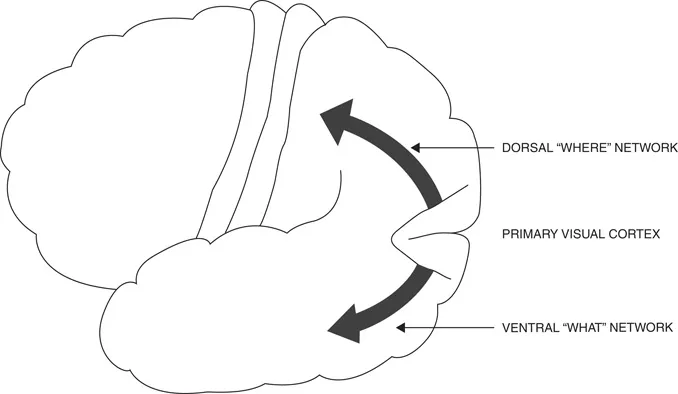

Each of these primary sensory areas in the cerebral cortex (Figure 1.4) sends this analyzed information to their modality-specific sensory association area. The primary visual cortex sends information to two different sensory association networks (Figure 1.5). One is lower down in the brain and is called the ventral (bottom) stream, and the other is higher up and is called the dorsal (top) stream. These association areas perform visual perceptual processing. They receive the elementary sensory information from the primary visual cortex and develop shapes and patterns. In addition, the more ventral stream stores memories of previously viewed objects, such as faces, objects, and words. The right hemisphere ventral stream appears to be more important in the perception of faces and the left in the perception of objects and written words. Thus, Mishkin and Ungerleider (1982) called this visual processing network the “What” stream. When this area is injured by a disease such as a stroke, the patient develops a disorder called “visual agnosia.” The word agnosia comes from Greek: a = with and gnosis = knowledge. Patients who have visual object agnosia can see and have good acuity, but with object agnosia, they cannot recognize objects (Lissauer, 1890). Patients with prosopagnosia cannot recognize the faces of people who they know. Patients with these injuries are impaired in recognizing objects or faces because the memories of how objects look are stored in these regions. However, if a person with prosopagnosia hears the voice of someone they know, they will be able to recognize this person.

Figure 1.5 Dorsal “where” and ventral “what” visual networks. After visual information from the eyes comes back to the occipital cortex and is processed by this cortex, information is sent to visual associations areas. In general, there appears to be two major visual processing networks. One of these networks that is higher (dorsal) appears to be important in determining spatial location (i.e. where, in relation to the viewer’s body, a visual stimulus is located). This network has been called the “Where” system. The other lower (ventral) network is important for being able to recognize objects (including faces) and has been called the “What” network.

Bálint (1909) described patients who could recognize objects, but when attempting to point to these objects or pick them up with their hand, they did not appear to know their location. He called this disorder “optic ataxia.” He also reported that these patients had trouble moving their eyes to the correct position to see an object. Typically, patients with this disorder have lesions on their dorsal (top) parietal and occipital lobes. Mishkin and Ungerleider (1982) called this dorsal processing network the “Where” stream.

These visual, auditory, and somatosensory areas all send connections to the inferior parietal lobe. Therefore, this area is called the polymodal cortex. In the inferior parietal lobes, there are interactions between these sensory networks that allow people to know how to successfully interact with their environment. The left hemisphere’s inferior parietal lobe is also more important in the spatial and temporal aspects of movement programming, and the right hemisphere’s inferior parietal lobe is important in the allocation of attention. Both inferior parietal lobes are also critical for many cognitive activities.