Building Knowledge, Constructing Histories, volume 2

Proceedings of the 6th International Congress on Construction History (6ICCH 2018), July 9-13, 2018, Brussels, Belgium

- 696 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Building Knowledge, Constructing Histories, volume 2

Proceedings of the 6th International Congress on Construction History (6ICCH 2018), July 9-13, 2018, Brussels, Belgium

About this book

Building Knowledge, Constructing Histories brings together the papers presented at the Sixth International Congress on Construction History (6ICCH, Brussels, Belgium, 9-13 July 2018). The contributions present the latest research in the field of construction history, covering themes such as:

- Building actors

- Building materials

- The process of building

- Structural theory and analysis

- Building services and techniques

- Socio-cultural aspects

- Knowledge transfer

- The discipline of Construction History

The papers cover various types of buildings and structures, from ancient times to the 21st century, from all over the world. In addition, thematic papers address specific themes and highlight new directions in construction history research, fostering transnational and interdisciplinary collaboration.

Building Knowledge, Constructing Histories is a must-have for academics, scientists, building conservators, architects, historians, engineers, designers, contractors and other professionals involved or interested in the field of construction history.

This is volume 2 of the book set.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Research Foundation Flanders, Brussels, Belgium

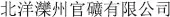

Year | Total quantity | Imports from/re-exports to | |

Fire brick (pieces) | Fire clay (piculs **) | ||

1864 | 17,036 | – | Imports from Great Britain |

1864 | 10,000 | – | Imports from USA |

1864 | 2540 | – | Imports from Australia |

1864 | 10,000 | – | Re-exports to Japan |

1866 | 6493 | – | Imports from Great Britain |

1867 | – | 15 | Imports from Great Britain |

1868 | – | 16.80 | Imports from foreign countries |

1871 | – | 420 | Imports from foreign countries |

1879 | – | 344.4 | Imports from foreign countries |

1881 | – | 1929.42 | Imports from foreign countries |

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Pier Luigi Nervi and Fiat. The expansion of Officine Mirafiori in Turin

- The vaulted roof of San Vittore in Milan: An unusual sixteenth-century construction

- The evolution of the cast node of the Pompidou Centre: From the ‘friction collar’ to the ‘gerberette’

- German stonemasons and the fort architecture of the Texas frontier

- The Chinese teahouse at the 1873 Vienna world exposition

- Documenting depression-era construction: The University of Virginia’s PWA buildings

- King’s College Chapel: The geometry of the fan vault

- Late Antique vaults in the cisterns of Resafa with ‘bricks set in squares’

- Evolutionary traces in European nail-making tools

- Arch bridge design in eighteenth-century France: The rule of Perronet

- ‘Recommended minimum requirements for small dwelling construction’. A forgotten ancestor of the modern USA building code

- Earthen buildings in Ireland

- Iron on top. The use of wrought iron armatures in the construction of late Gothic openwork spires

- The Munich state opera house. Constructing between tradition and progress at the beginning of the nineteenth century

- The roof of the Marble Palace in Saint-Petersburg: A structural iron ensemble from the 1770s

- Modernity and locality in the use of brick in Spanish architecture (1870s–1930s)

- Study of traditional gypsum in Spain: Methodology and initial results

- Interdisciplinary research on the heritage of housing complexes in France (1945–75)

- Earthen mortar walls in Cremona: The complexity and logic behind a construction technique

- Geometry and proportions of the medieval castles of Latvia

- New typology for Old & Middle Kingdom stone tools: Studies in the Hatnub quarries in Egypt

- Luigi Moretti and the program of the case albergo in Milan (1947–50)

- Hydrotechnical models of the ‘Modellkammer’ (chamber of models) in Augsburg, Germany

- Abandonment of sexpartite vaults: Construction difficulties and evolution

- Late Gothic constructions in Müstair and Meran

- Built-in, exposed or concealed comfort services. Attempts to industrialise collective housing after 1945

- The Portland cement industry and reinforced concrete in Portugal (1860–1945)

- Origins of the modern cable-stayed bridge: The Dischinger story

- Frederick Lanchester and the invention of the air-supported roof

- Catetinho: The first presidential house in Brasília, Brazil

- Some aspects of steel building construction of the industrial architecture in the United States (1890–1930)

- Iron bridges for Rome, the capital of the Kingdom of Italy

- The hyperbolic paraboloids of the Tor di Valle racetrack in Rome

- The secret of zoomorphic imposts: A new reading of the Achaemenids’ roofing system

- The dome of Saint-Paul-Saint-Louis in Paris, a historical and structural analysis

- Braided rope with vegetable fibers for the construction of the Inca bridge of Q’eswachaka (Peru)

- Church of Mission San José, San Antonio: Using construction history to inform preservation approaches

- Knowledge transfer in vaulting. The Assier church and Valencian stonecutting

- Nineteenth-century stone protection: The invention and early research on fluosilicates and their dispersion into Europe

- The Boyne Viaduct: Early indeterminate lattice girder analysis and design

- Sixteenth-century development from common rafter roofs to ridge purlins in Leiden (NL)

- European iron bridges in Puerto Rico: The example of the Guamaní bridge

- Accouplement: Vicissitudes of an architectural motif in classical France

- Fabrication and erection of large steel bridges in the twentieth century: From structural analysis to optimisation of fabrication

- Production of major public works in Brazil: From the scenes in documentaries from 1950–70 to an interrogation about the contemporary specificities of state-company relations

- Early Greek stone construction and the invention of the crane

- Experimental school constructions by Jean Prouvé. The benefit of closed prefabrication

- Sheltered. Parked. Respirated. Three underground spaces by Gottfried Schindler

- Dutch natural stone: Interpretation of a vernacular building material in modern architecture

- Late Gothic system in the church of Saint-Séverin (Paris)

- Recent geopolitics of construction – origins and consequences

- Pier Luigi Nervi’s idea of “vertità delle strutture”

- ‘Theory’ and systematic testings – Emil Mörsch, Carl bach and the culture of experimentation into reinforced concrete construction at the turn of the twentieth century

- A timber bridge constructed in seventeenth-century Japan: Study of innovation in the construction of Kintai Bridge and its maintenance techniques

- François Coignet (1814–88) and the industrial development of the first modern concretes in France

- Assessing geometrically the structural safety of masonry arches

- A masterpiece in the use of light, Johnson Wax headquarters. Racine, Wisconsin, USA

- The Church of Peace in Jawor: A few remarks on the organization of its construction in the years 1654–56 in the light of written and iconographic sources

- Nubia vernacular: The villages of Bigge

- Beyond Grubenmann: Swiss carpentry (1750–1850)

- Transfer of knowledge through books and prints: Jesuit design for the Western buildings and fountains in the Yuanmingyuan in Beijing

- Earthquake-resistant foundations systems in Italy in the first decade of the twentieth century

- Specifications and the standardisation of Ireland’s local harbours

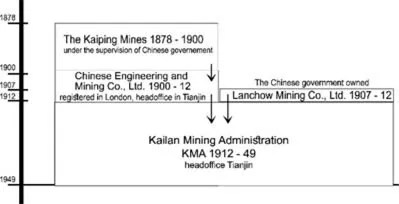

- Fire brick in China: From mining to architecture

- New experiences with reinforced tile for Eladio Dieste when building the Cristo Obrero Church

- Competing visions of community, commerce and construction in the first Ohio River railroad bridge

- Knowledge transfer in the early medieval art of vaulting in Dalmatia

- Onsite precast concrete: A critical approach to concrete at the Faculty of Engineering, Prince of Songkha University, Thailand

- Adobe constructions in Yún-lín county, Taiwan

- The vaulted system of the Basilica of S. Ambrogio in Milan: A cross-feature in the Basilica’s life. Restoration and interpretation

- At the intersection of foreign building know-how: Plovdiv in the early twentieth century

- The influence of Howe’s structural typology on Galician wooden bridges

- The mushroom column: Origins, concepts and differences

- The thirties summer holiday camps in the Abruzzo region: From design to building

- The first Luanda’s skyscraper: Comfort through natural and artificial control methods

- Victor Horta and building site photography

- Business-card buildings: Corporate architecture and promotional strategies in buildings and projects for Eternit in Belgium (1955–75)

- The foundations of the Nieuwe Kerk Tower in Amsterdam (1645–52)

- Joining techniques in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Belgian timber roofs

- Education on the production chain: Lelé’s transitory schools in Brazil

- Innovations in the structural systems in tall buildings in Bogotá in the 1960s. Case study: Bavaria building

- William Arrol and Peter Lind: Demolition, construction and workmanship on London’s Waterloo Bridges (1934–46)

- Reverse engineering marvelous machines: The design of Late Gothic vaults from concept to stone planning and the prehistory of stereotomy

- Emergence of heavy contracting in the United States in the nineteenth century

- Hidden modernity: Reinforced concrete trusses in Brussels parish churches (1935–40)

- Built to stock. Versatility of Hennebique’s urban warehouses in Belgium (1892–1914)

- Author index