The End of the Cold War and the Return to Europe

The end of the Cold War has generated considerable speculation about the prospects for future East-West European relations. Many observers have argued that the Cold War bipolar military division of Europe would be replaced with a set of broader and more diffuse security challenges within which economic issues would come to play an increasingly important role. In the early 1990s, this new security agenda threw up questions about the future evolution of the European Community (EC)1 and, more particularly, the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO). Whereas the EC could safely assume that it would continue as a trading association of some nature, NATO’s raison d’être had been based upon the perceived Soviet threat. Once this was removed, NATO came under growing pressure to justify its continued existence amidst expectations of a ‘New World Order’ and the anticipated peace dividend it would yield.

There are a number of important differences in terms of how the EU and NATO debates on enlargement have subsequently developed. Where the EU is concerned, the end of the Cold War represented the opportunity to continue the process of building pan-European unity as envisaged by many of its founding fathers in the 1940s and 1950s. NATO, on the other hand, had been established out of European division and disunity and had been seen by the Western European states as a necessary means of resisting the Soviet military threat. The end of the Cold War brought the very existence of NATO into question. The EU and NATO therefore found themselves at quite different intellectual starting points in 1989-90.

The emerging democracies of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) were clear that their benchmark of success in the system transformation process was entry into western organisations. The Visegrad Declaration signed in February 1991 by Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Poland pledged mutual support towards this objective, in particular entry into the EC and NATO, and was phrased within the context of a ‘Return to Europe’. Neither organisation was prepared to define a clear position on enlargement immediately after the end of the Cold War and this prompted the criticism that attempts by the CEE states to obtain membership of the EU and NATO were like trying to board a moving train. Speaking to the General Assembly of the Council of Europe in October 1993, the Czech President, Vaclav Havel, condemned what he perceived to have been an overly bureaucratic attitude of the West in responding to Central and Eastern Europe:

The Europe of today lacks an ethos, imagination, generosity, the ability to see beyond the horizon of particular interests be they partisan or otherwise, and to resist pressures from various lobbies. It lacks a deep identification with the genuine meaning and purpose of integration efforts. It is as though it has simply not achieved a profound sense of responsibility for itself as a whole and thus for the genuine prospects of success for all those who live in it now, and in the future.2

Havel’s position is typical of those stressing the moral imperative for enlargement. Although not immune, both the EU and NATO have resisted this approach but have been equally reticent in producing other justifications for their respective enlargement processes. Taken overall, the prospective benefits of EU and NATO enlargement may be summarised as being the following:

Enlargement will enhance the power of the European Union and increase its influence over other political and trading blocs.

Enlargement will increase the size of the European single market and, in doing so, generate access to new and wider markets for both EU and accession states. The entry of the accession states will also offer new production locations for EU enterprises and contribute to greater market competition. The net effect will be a more flexible market and growth in prosperity.

Where NATO is concerned, enlargement will generate a new rationale for its continued existence beyond the Cold War (‘extending security eastwards’) and will provide a means of maintaining US engagement in Europe.

Enlargement of both the EU and NATO will assist in the stabilisation of political tensions in Central and Eastern Europe, a region that has demonstrated considerable political instability in previous centuries. In particular, enlargement will contribute to the reconciliation of border relationships prone to conflict, such as between Germany and Poland, and will also help to damp down the potential for ethnic conflict in those CEE states seeking to join, as between Hungary and Romania.

Enlargement of both the EU and NATO will result in greater international confidence in the region of Central and Eastern Europe and thus hold out the prospect of increased inward flows of foreign direct investment.

There are, however, a number of prospective costs arising from enlargement:

The majority of accession states will be net beneficiaries from the European Union budget and this will result in considerable financial transfers flowing out of the current member states into Central and Eastern Europe.

The accession states have different historical experiences concerning socio-economic development and the growth of democracy. These factors could have an impact upon the institutional frameworks, decision-making processes and policy outputs of both the EU and NATO.

The enlargement of the EU could provoke socio-economic and political tensions in Western Europe if unemployment levels increased as a result of enterprises shifting production locations to low wage-cost areas and due to increased market competition.

Enlargement is unlikely to embrace Russian membership in either institution and this could provoke a permanent deterioration in relations with what remains a potentially powerful economic, political and military actor.

The end of the Cold war has prompted reconsideration of both the European integration process and European security architecture. The central concern in this investigation is the nature of the political response provided by EU and NATO member states in supporting post-communist transformation in Central and Eastern Europe. A number of authors have speculated that the absence of an appropriate response to the transitional tensions in the region could provoke long-term instability leading to the degeneration into political authoritarianism.3

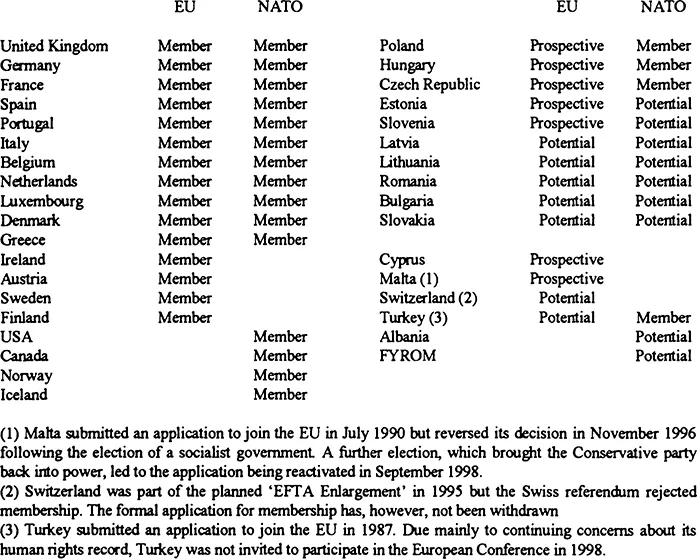

In 1998 eighteen states were queuing up to become members of either the EU, NATO or both. These states can be divided into two categories. Firstly there are the prospective members; i.e. those who can be reasonably confident that they will become members of at least one of the western-based institutions at some point in the future. Secondly there are the ‘potential’ members. This is a diplomatic term frequently used to describe those whose prospects are less certain. Since the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland became members of NATO in March 1999, eleven states are currently members of both the EU and NATO, four states are EU members only and eight states are NATO members only. There are currently seven prospective and seven potential members of the EU and nine potential members of NATO.

Table 1:1 European Union and NATO Members

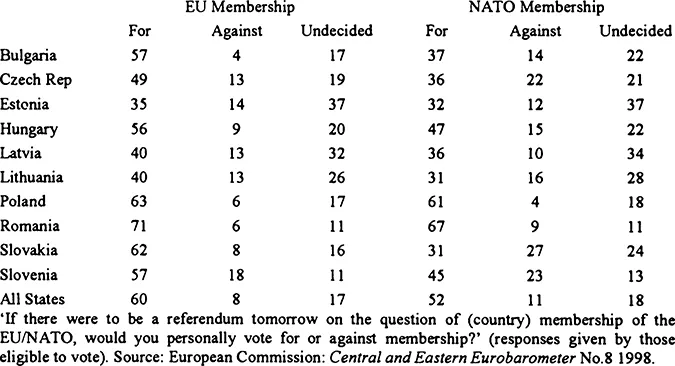

Membership of the EU and NATO has the broad support of the electorates concerned as data provided by the EU Commission in 1998 in Table 1:2 overleaf suggests. According to this data, there has been clearer support for membership of the EU than of NATO. Using an open ended response question, those who opposed NATO membership did so out of a desire to remain neutral (6 per cent of all respondents), out of pacifist motivations (6 per cent) or because of the financial burden (5 per cent). 6 per cent of all respondents suggested that EU membership would worsen the economic crisis, would be too expensive or of no benefit. 2 per cent suggested that EU membership would result in a loss of identity or independence, another 2 per cent felt the EU was acting out of self-interest and 1 per cent thought EU membership would promote instability and disintegration. 35 per cent of all respondents in favour of EU membership cited the general progress membership would facilitate, 25 per cent supported it because of the anticipated economic improvements and 17 per cent because of higher living standards. Not surprisingly, 52 per cent of those in favour of NATO membership cited the security guarantee and stability it would facilitate with another 6 per cent specifically stating security against Russia. 13 per cent stated that NATO would control and reform their country’s military apparatus and another 10 per cent suggested that NATO membership would foster general progress and co-operation.

Table 1:2 CEEC Attitudes towards EU and NATO Enlargement

The establishment and maintenance of a civil society in Central and Eastern Europe is arguably the most difficult aspect of the system transformation process to predict. Whereas the ‘formal’ démocratisation process; i.e. constitution, party-system, elections and marketisation can be externally supported and even directed, the creation of a public participatory and, by implication, supportive political culture depends upon the political legitimacy that Central and Eastern European electorates afford to the post-communist regimes. When in 1989 the Soviet empire in the then Eastern Europe collapsed, it was correctly pointed out that this had occurred in the main due to the implosion of the command economic system and failure of the political elites to satisfy the material aspirations of the masses.4 It is by the same measurement that electorates in the CEE states will assess the success of the post-communist regimes. The danger is that an expectations gap will develop that cannot be satisfied by pro-western post-communist political elites and that disenchantment will foster the creation of less amenable and undemocratic political systems.

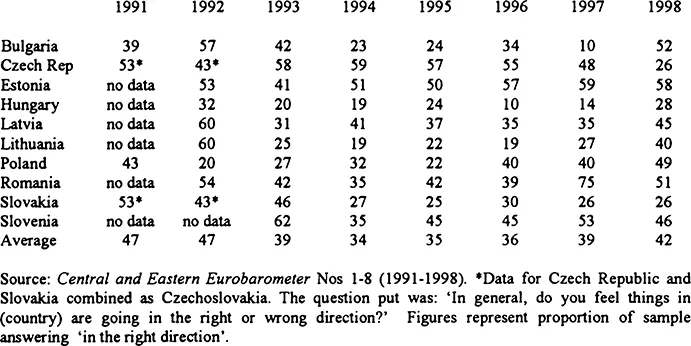

The European Commission has conducted an annual survey into political opinions in Central and Eastern Europe since 1990. Although the data is prone to volatility, grounds appear to exist for cautious optimism in terms of the general assessment of the transformation process. Attitudes towards post-communist society are generally more positive among the ‘ins’ (EU jargon for prospective members) as opposed to the ‘pre-ins’ (those with less prospect of joining). However, as was the case during much of the Cold War period, Hungary and Romania tend to be exceptions to the rule. Hungary has recorded considerably lower optimism compared to the other ‘ins’ throughout the post-communist period. In the 1998 survey however, the proportion of the sample answering that the country was going in the wrong direction was lower in Hungary (53 per cent) than in the Czech Republic (60 per cent) or Slovakia (64 per cent). Romanians, on the other hand, have developed a much more optimistic perspective in recent years, which can be attributed to the change in government and implementation of reforms from 1996.

Table 1:3 CEEC Attitudes to Post-Communist Transformation

It would be a spurious exercise to attempt to explain this data in mono-casual terms and particularly in reference to the prospects for accession to the European Union. The question asked purposely refrained from disentangling attitudes towards economic, political and social issues and, as such, was designed towards providing a general assessment of each nation’s progress in the transformation process rather than in the context of any individual factor.

If the European Commission provides an upbeat evaluation of the data, it remains the case that only one state, Estonia, has recorded a majority of the sample as having a positive attitude towards their country’s prospects on a consistent basis. In research conducted in the mid-1990s, Rose and Haerpfer suggested that a degree of frustration would be inevitable during the transformation process. The real test, it was proposed, was whether the future prospects were considere...