eBook - ePub

Prostate Cancer Imaging

An Engineering and Clinical Perspective

- 376 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Prostate Cancer Imaging

An Engineering and Clinical Perspective

About this book

This book covers novel strategies and state of the art approaches for automated non-invasive systems for early prostate cancer diagnosis. Prostate cancer is the most frequently diagnosed malignancy after skin cancer and the second leading cause of cancer related male deaths in the USA after lung cancer. However, early detection of prostate cancer increases chances of patients' survival. Generally, The CAD systems analyze the prostate images in three steps: (i) prostate segmentation; (ii) Prostate description or feature extraction; and (iii) classification of the prostate status.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 | History of Imaging for Prostate Cancer |

CONTENTS

The History of Ultrasonography

Development of Medical Ultrasonography

Transrectal Ultrasonography

History of Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Conventional MRI

Multiparametric MRI

Imaging for Prostate Cancer Staging

Conclusions

References

The detection of prostate cancer has primarily been based on the use of serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) along with a digital rectal exam (DRE). Prior to the introduction of transrectal ultrasound, digital guidance was used for the performance of prostate biopsies. The improvements in medical imaging have allowed for the ability to detect clinically significant lesions as well as the extent of disease (1).

THE HISTORY OF ULTRASONOGRAPHY

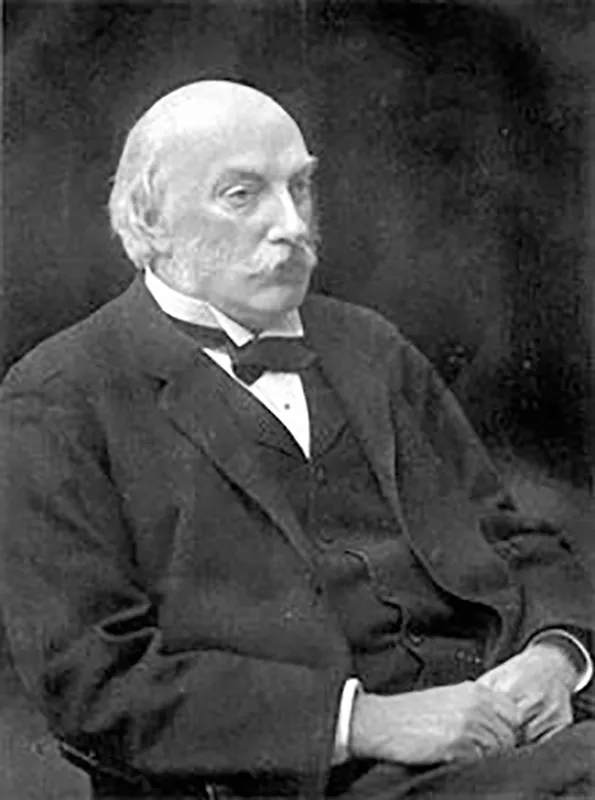

Studies during the nineteenth century into the measurement of the speed of sound in water paved the way for the development of SONAR (SOund Navigation And Ranging) (2). Jean-Daniel Colladon, a Swiss physicist, in 1826 performed an experiment where he struck an underwater bell in Lake Geneva and simultaneously ignited gunpowder. The flash of the gunpowder was observed by Colladon 10 miles away and he heard the sound of the bell with an underwater trumpet. By measuring the time interval between these two events, Colladon was able to calculate the speed of sound in a body of water (Lake Geneva) (3). This experiment has been seen as the birth of underwater acoustics. John William Strutt (also known as Lord Rayleigh) was a physicist, who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1904 for discovering the element Argon. He predicted the existence of surface acoustic waves that travel on the surface of solids (called Rayleigh waves) and, in 1877, published The Theory of Sound, which became the foundation for the science of ultrasound (4) (Figure 1.1).

In 1880, Pierre and Jacques Curie made an important discovery that eventually led to the development of the modern-day ultrasound transducer. The Curie brothers observed that when pressure was applied to crystals of quartz an electric charge was generated (3). The charge was directly proportional to the force applied to it and the phenomenon was called “piezoelectricity” from the Greek word meaning “to press.” Current ultrasound transducers contain piezoelectric crystals.

On April 15, 1912, the Titanic sank in the North Atlantic after striking an iceberg, and the ensuing public outcry led to significant interest in the development of a device to detect underwater objects (2). Constantin Chilowsky, a Russian expatriate living in Switzerland, was an electrical engineer who became interested in echo ranging because of the sinking of the Titanic. German U-boat attacks on Allied shipping heightened his interest in developing SONAR (5). In 1915, Chilowsky developed a working hydrophone in conjunction with Paul Langevin, an eminent French physicist. Their work contributed much to the knowledge of generating and receiving ultrasound waves, which was an important part of the pulse echo principle of SONAR. Funding for research was exhausted at the end of World War I and the efforts shifted toward measuring the depth of the ocean floor. The quest for naval superiority and the submarine versus antisubmarine battles of World War II renewed interest in SONAR development (2).

FIGURE 1.1 John William Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh (1842–1919).

An understanding of the historical milestones of ultrasound require knowledge of transmission and pulse reflection methods, as well as A, B, and M modes of ultrasound. Early ultrasound used the transmission method where ultrasound measured the ultrasonic waves that passed through a specimen (6). The amount of sound waves not absorbed from the intervening tissue was recorded. The pulse reflection method placed the receiver and transmitter on the same side of the specimen and the amount of sound reflected was then recorded. Amplitude or A-mode was a one-dimensional image that displayed the amplitude or strength of a wave along the vertical axis and time on the horizontal axis (2). Brightness or B-mode, which is commonly used today, is a two-dimensional characterization of tissue where each dot or pixel on the screen represents an individual amplitude spike. In currently used models, amplitudes of varying intensity are assigned shades from black to white. M-motion or motion mode ultrasound relates the amplitude of the ultrasound wave to the imaging of moving structures (such as cardiac muscle).

DEVELOPMENT OF MEDICAL ULTRASONOGRAPHY

George Ludwig and Francis Struthers, working at the Naval Medical Research Institute in Bethesda, Maryland, were among the first to use echo technique in biologic tissue. Because they were employed by the military their work was considered restricted information and was not published in medical journals (2).

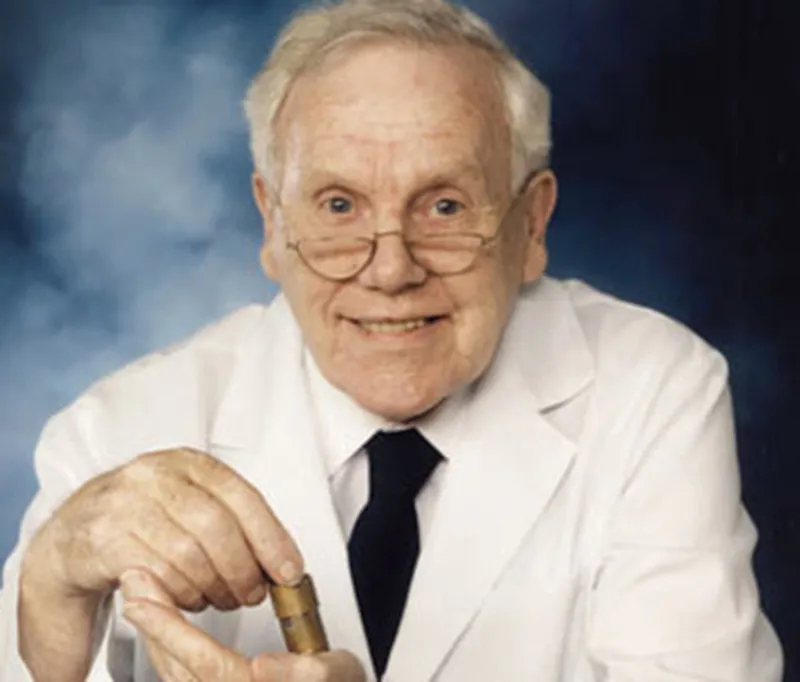

John Julian Wild was an English-trained surgeon who immigrated to the United States after World War II (Figure 1.2). Working in Owen Wangensteen’s laboratory at the University of Minnesota, using A-mode imaging and a 15 MHz transducer, Wild measured the thickness of the bowel wall in a large water tank (7). Ahead of his time, Wild felt that “it should be possible to detect tumors of the accessible portions of the gastroenterological tract both by density changes and also in all probability of the tumor tissue to fail to contract” (2). Wild managed to develop a scanning device that was used to screen patients for breast cancer and also developed transrectal and transvaginal transducers (2,8). With this instrument he imaged a brain tumor in a pathology specimen and localized a brain tumor in a patient after a craniotomy (2).

FIGURE 1.2 John Julian Wild (1914–2009).

Douglass Howry played an important role in the development of ultrasound and ultrasonic devices in the 1940s. Unlike Wild, Howry worked more on the development of the equipment and the applied theory of ultrasound rather than on its clinical application. Howry’s goal was to produce an instrument that was “in a manner comparable to the actual gross sectioning of structures in the pathological laboratory” (9). Working with W. Roderic Bliss, an electrical engineer, Howry built the first B-mode scanner in 1949. In the late 1950s, Howry and colleagues developed an ultrasound scanner with a semicircular pan containing a plastic window that was later developed into a direct-contact scanner. In 1961, Ralph Meyerdirk and William Wright produced the prototype for the first handheld contact scanner in the United States (10). Ian Donald at the University of Glasgow used an A-mode ultrasound machine to differentiate various types of tissues in recently excised fibroids and ovarian cysts. Donald and his colleagues in Glasgow contributed significant research in regard to ultrasonography in the field of obstetrics and gynecology. He incidentally discovered that a full urinary bladder provided a natural acoustic window for the transmission of ultrasound waves through the pelvis, thus allowing pelvic structures to be imaged more clearly (2,11).

TRANSRECTAL ULTRASONOGRAPHY

Anatomic ultrasound imaging is the oldest and most widely used technique to image the prostate. Watanabe et al. were the first to describe the use of transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) imaging of the prostate with a 3.5 MHz transducer in 1974 (12,13). Prostate cancer lesions have been classically described as hypoechoic lesions on TRUS imaging (14,15). However, the low specificity and positive predictive value (PPV) of TRUS imaging was a clear limitation as other conditions such as prostatitis or focal infarcts could also show hypoechoic characteristics. Lee et al. showed that the positive predictive value of TRUS by itself was 41%, the PPV dropped to 24% if the DRE was normal, 12% if the PSA was normal, and only 5% if both the DRE and PSA levels were normal (16). In 1989, Hodge et al. explored the utility of adding lesion-directed biopsies to specific hypoechoic areas found on ultrasound compared to the standard non-targeted TRUS-guided systematic prostate biopsy. In 136 men with abnormal prostates on DRE, they found that directed biopsies toward hypoechoic areas within the prostate added very little yield since in 80/83 patients, prostate cancer was detected by the non-targeted systematic biopsies. The addition of TRUS-guided cores to hypoechoic lesions increased the yield by only 5% (17). Thus TRUS imaging by itself has been inadequate for the diagnosis, characterization, and targeting of prostate cancer due to poor resolution, low specificity, and its negative predictive value. The main concerns of the technique include failure to detect prostate cancer (due to poor spatial resolution of lesions), inaccurate risk stratification (from under sampling in cases of small volume disease, transition zone or anteriorly located tumors) and high detection rate of small clinically insignificant prostate cancer (18,19,20). Most prostate cancer tissue is known to be harder or stiffer than normal prostate tissue (the digital rectal exam is predicated on the physician detecting harder or abnormal lumps of cancer tissue). With real-time elastography imaging tissue, the physician induces a mechanical excitation in the prostate tissue and then images the response using real-time ultrasound (21). Techniques include strain elastography, acoustic radiation force impulse imaging, and shear wave elastography. Despite some promising results, an absolute quantitative threshold to distinguish benign from malignant tissue still remains to be determined. Thus transrectal ultrasound guidance continues to be used principally to guide systematic 12-core biopsies of the prostate.

HISTORY OF MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING

Nikola Tesla discovered the rotating magnetic field in 1882. In 1937, Columbia University Professor Isidor Rabi, working at the Pupin Physics Laboratory in New York City, recognized that the atomic nuclei show their presence by absorbing or emitting radio waves whe...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Editors

- Contributors

- Chapter 1 History of Imaging for Prostate Cancer

- Chapter 2 Transrectal Ultrasound (TRUS)-Guided Prostate Biopsy: Historical Perspective and Contemporary Clinical Application

- Chapter 3 Current Active Surveillance Protocol for Prostate Cancer

- Chapter 4 Prostate MRI

- Chapter 5 Current Role and Evolution of MRI Fusion Biopsy for Prostate Cancer

- Chapter 6 Current Role of Focal Therapy for Prostate Cancer

- Chapter 7 High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound (HIFU)

- Chapter 8 Current Role of Cryotherapy in the Treatment of Prostate Cancer

- Chapter 9 Transperineal Mapping of the Prostate for Biopsy Strategies

- Chapter 10 Computer-Aided Diagnosis Systems for Prostate Cancer Detection: Challenges and Methodologies

- Chapter 11 Early Diagnosis and Staging of Prostate Cancer Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging: State of the Art and Perspectives

- Chapter 12 A DCE-MRI-Based Noninvasive CAD System for Prostate Cancer Diagnosis

- Chapter 13 Prostate Segmentation from DW-MRI Using Level-Set Guided by Nonnegative Matrix Factorization

- Chapter 14 Automated Prostate Image Recognition and Segmentation

- Chapter 15 Precision Imaging of Prostate Cancer: Computer-Aided Detection and Their Clinical Applications

- Chapter 16 Computer-Aided Diagnosis of Prostate Magnetic Resonance Imaging: From Bench to Bedside

- Chapter 17 Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the Detection of Prostate Cancer

- Chapter 18 Diagnosing Prostate Cancer Based on Deep Learning with a Stacked Nonnegativity Constraint Autoencoder

- Chapter 19 MRI Imaging of Seminal Vesicle Invasion (SVI) in Prostate Adenocarcinoma

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Prostate Cancer Imaging by Ayman El-Baz, Gyan Pareek, Jasjit S. Suri, Ayman El-Baz,Gyan Pareek,Jasjit S. Suri in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Biotechnology in Medicine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.