- 206 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book, first published in 1978, analyses the underlying structure of the Indonesian mass-based economy and its problems, and goes on to show how the hectic economic activity after 1965 failed to come to terms with the real needs of the people. It divides the new Indonesian economy into endogenous and exogenous parts in order to highlight the gulf between 'growth' and 'development'.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Indonesian Economy Since 1965 by Ingrid Palmer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Development Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

The term ‘political economy’ is used in the title of this book to focus attention on the incessant interaction of political and economic life. To talk of‘the economy’ alone is to imply that this aspect of life has a relentless, but objective, imperative of its own constrained by the limits of resources whose active dimensions are independent of non-economic or non-physical factors. More importantly, the awareness of political economy is an aid to identifying the sectoral flow of surpluses and their availability for re-investment. By awarding greater recognition to the dichotomy of private and social profit one is less inhibited when viewing the internal consistency of a strategy of overall development and of the feasibility of maintaining the momentum of its general thrust. To challenge the hegemony of mere economic analysis is to question why price distortions and market imperfections are so obsessionally seized upon by development economists when the viability of a strategy is suspect for far more obvious and significant reasons. It is to question why a system of thought which reduces human contribution to development either to profit-maximising entrepreneurship or to units of labour ever gained such popular currency. It is to question why a country should be obliged to aim at the outer edge of its national material production possibilities, with only passing reference to social and political possibilities.

We know, of course, that the expression ‘the most efficient allocation of resources’ is highly subjective to the prevailing distributions of income, assets and political power as well as to artificially created wants. And yet it is a response which is chanted with unfailing religious reverence by western economists. We all know the gross astigmatisms of theoreticians, yet the reverence continues.

Indonesia is such a huge archipelagian country with its full share of dualisms and pluralisms that there are as many optimal plans for it as there are places from which to view the country. For this reason any attempt to utilise the theory of comparative advantage will be damaging to some people’s livelihoods and so to power balances. The theory as it was applied to East Pakistan jute exports intended to finance West Pakistan’s industrialisation gave birth to Bangladesh. The same relation, pushed hard between Sumatra and Java, could produce a similar result for Indonesia. The theory of comparative advantage must always flounder in the issues of ‘whose advantage?’, and ‘subject to which political feasibilities?’.

The other main theory which is worshipped as intellectual manna is that of equating economic opportunity costs at the margin. This theory states that if a resource can earn more in another employment its current employment has an opportunity cost and that its allocation is therefore sub-optimal. Apart from the fact that the market value of resources in alternative employments will vary for every distribution of income and wealth, it ignores the implications of one important factor of production always reproducing and multiplying itself in a manner largely independent of its economic return. This peculiar characteristic of labour has never been properly accommodated in the body of economic theory except in scarcely veiled suggestions that the working class should be prevented from breeding. This indifference to human needs, and the implicit assumption that human beings are there to serve the economy and that the economy is not there to serve the people, explains the strange omission in the literature of a term such as ‘nutritional opportunity cost’: that is to say, that a strategy being followed may have a higher cost in terms of malnutrition or undernutrition than alternative strategies. Likewise the absence of political and social opportunity costs; though less so because, whereas there is no known case of an economist starving some have been known to fall from power for causing political trouble, and they act as an example to others.

This study of Indonesia describes the intended and actual sectoral growth patterns since 1966 and the likely effect of both on overall development.

In designing this study there were found to be difficulties of bringing order to an analysis of the economic changes. For example, should there be separate chapters on foreign investment and domestic investment? If so, how does one record what is rehabilitation and what is expansion, a distinction which is so important?

It was finally decided that the separation of rehabilitation and expansion was the more valuable design for several reasons, chiefly:

- With the emergence of so many major new characteristics of the economy the fortunes of the original mass endogenous (and indigenous) economy needed special treatment. Since it was in the rehabilitation process that labour-intensive mass livelihoods were to be found rather than in new technological investment (whether domestic or foreign) the extent of real rehabilitation had to be recorded on its own.

- Although the conflict of foreign investment versus domestic investment is dear to the hearts of both the international left and the Indonesian middle class it is seen differently by the majority of Indonesians. Given half a chance Indonesian investors would follow foreign investors into the same enclave industries, would also remit profits overseas, would do the same ecological damage, and would use the same capital-intensive technology. The effect therefore of net investment in new industries on the body of the economy would be the same for both domestic and foreign investments.

- With the emergence of the pribumi (indigenous Indonesian ownership of capital) issue, of the obligatory joint venture, of the stock exchange and the transfer of shares in foreign enterprises the rivalry between foreign investors and the Indonesian middle class is being resolved politically and institutionally. From the point of view of the Indonesian masses foreign and domestic investors combine into the new ruling class. Since they have a common high consumption culture, and indeed almost a common language (English), the foreign investment issue is more accurately described as an alien techno-cultural investment issue. What is now foreign-owned is, in fact, kept hostage in the country for the benefit of the new middle class.

- There remains, of course, the factor of economic nationalism and it has a bearing on the future managerial quality of post-1965 investments. Moreover, the transfer of title to capital from foreign hands to pribumi hands makes an interesting political study. Thus provision has been made to describe these changes in a later chapter after the rehabilitation and expansion issues have been covered.

Thirty years after independence the economic structure of Indonesia bears characteristics which are reminders of the last hundred years of colonial rule. Until the turn of this century colonial development was almost exclusively on Java with the aim of providing a cheap supply of dessert crops, such as coffee, tea, tobacco and spices as well as sugar. The Culture System (1830–1870) had obliged Javanese farmers to cultivate certain export commodities which were highly lucrative to the European-Indies trade, and had set the pattern of Java’s present production. The fine allocation of land resources and attempts to raise crop yields led to a rapid increase in Java’s population during the nineteenth century. Although enjoying only 12 per cent of cultivable land in Indonesia (not allowing for double-cropping), Java today carries 60 per cent of the population. Poverty surveys at the turn of the century ushered in the Ethical Policy of health, public works and canal irrigation for rice cultivation. But industry was disallowed because it would have threatened Dutch home-based industries. The twentieth century exploitation of Banka, Biliton, Sumatra and Sulawesi for tin, rubber and copra came too late to redress this cruel demographic imbalance. Today Java’s population density averages out around 600 per square kilometre against Sumatra’s 42, Kalimantan’s 9, and Sulawesi’s 48. Transmigration efforts go back to 1900 but they reached a peak of only 47,600 persons annually in the years 1938–1941. Between 1957 and 1962 they had regained a (gross) level of 22,000 persons annually (Jones, June 1966).

Even before the Second World War Java was struggling to feed itself on its great rice industry and after independence it became plain that this island was increasingly to fail to pay its way. The dualism of the economic structure of the country was accompanied by the dualism of urban and rural life styles, which was most marked in Java.

Another legacy of the colonial past which still imposes a heavy burden on the development process is the nature of political growth. Colonial government was like an authoritarian one-party system. Since its raison d’être was to extract primary produce at a low cost the rural administration had to be efficient. After independence the administration became heavily urbanised and intellectualised as the cargo cult mentality of the educated elite led it to measuring its distance from backwoods rural people. The continued extraction of primary produce at a low cost was done less efficiently after independence because this political growth caused economic and infrastructural erosion. The sector producing the economic lifeline to the new state was left to be politically serviced by a rural elite. It has become increasingly apparent that this political dualism leaves two voices speaking at cross purposes, and this latent conflict as well as that between national Moslem businessmen in urban areas and military leaders, has become one of the most important justifications for a study of the political economy. For many years in Indonesia these underlying fractures between rural and urban interests and between entrepreneurial and parasitic interests were camouflaged by the exciting rivalry between the army and the Communist party which so obsessed foreign observers. Unfortunately the only force which had any chance of reconciling rural and urban interests and of substituting something new for the economic and civil order of colonial days, namely the Communist party, has been withdrawn from the scene. By removing the Communist party the national economic elite and the military-bureaucratic complex have unveiled their mutually antagonistic interests. It is only by the recent entry of enriched military officers into the modern economic sector that some of that antagonism has been reconciled.

The means of entry as well as the sectoral interests of foreign aid and investment are further reason for a recognition of political economy. The extent of foreign aid since 1966 has been greater than was predicted by the donors. Compared with the attention awarded other developing countries the interest lavished on Indonesia by rich industrialised countries and by international agencies cannot be explained by the country’s poverty. The terms on which foreign investment entered Indonesia, its choice of industry and its erosive effect on existing national industry, all indicate a bonanza for foreign investors, secured by preceding stabilisation and rehabilitation aid from the public international sector. The choices made by the foreign investors must always have more to do with optimising their interests than those of the recipient country.

The exploitation of resources in turn has determined the domestic distribution of income and wealth, both regionally and class-wise, setting up new parameters in the political economy. A minority of Indonesian nationals, especially a clique of Chinese, the military and the state oil company leadership, have found themselves in new powerful positions.

All these changes could not have occurred in the way and to the extent they did unless Indonesian political sovereignty was prostrate in 1966. Few would contest this. To understand how this came about and how low was the resistance of the national economy to the invasion of foreign funds the crisis of 1965/6 needs to be described.

Chapter 2

The Economic Crisis of 1965/6 and the Gamble Taken

Before describing the nature of the economic watershed it must be stated that the popular thesis that the events of 1965 were caused overwhelmingly by economic factors is erroneous. Newcomers to the Indonesian scene since 1965 have been so thoroughly propagandised by the economic verbiage of policies of stabilisation and rehabilitation that, without anyone saying as much in so many words, thay have frequently gained the impression that the political upheaval was necessary to save the economy. It would be more accurate to say that the economic extremities of the last few years of President Sukarno’s rule lent cover of confusion to the long-desired liquidation of the left.

No special brief is held here for the Communist party of Indonesia. But it is imperative to point out that, on balance, political forces which encourage the more effective developmental use of resources were enormously diminished by the massacres and arrests that took place, while those which obstruct that use were commensurately strengthened. The Communist party was easily the most important agent of change threatening the duality of poverty and privilege. That rehabilitation of a kind ever took place in these circumstances must be put down to the massive inflow of aid. Moreover, the political upheavals that followed in 1965/6 could hardly be said to have facilitated remedies to the economic crisis. The ferocity of the military is evidence in itself that a non-economic crisis of severe proportions was occurring concurrently with economic decline. The massacre and imprisonment of the left could not have relieved the burden of military expenditure on the budget, which all were agreed was the major cause of inflation. The suspension and regression of land reform was not going to raise the effective use of resources in agriculture.

THE NATURE OF THE FINANCIAL CRISIS

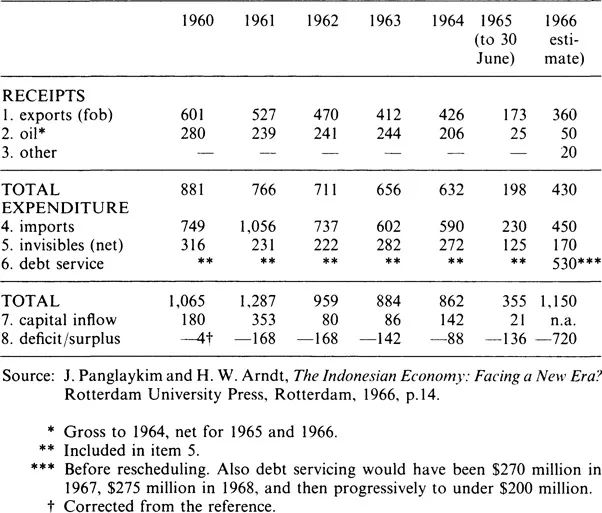

Having said this the extent of economic paralysis can be described. At the time the single most eloquent statistic was the total debt of about $2,300 million, of which about half was a Soviet and East European military debt. The immediate forecast, for 1966, was of foreign exchange earnings of $430 million (including oil) and minimum import requirements of $560 million; not to mention a debt servicing of $530 million. Rice import requirements were conservatively put at $30 million and imports of equipment, new materials and spare parts another $350 million (Panglaykim and Arndt, 1966). There were no reserves left, In fact, the only thing left in the national till were some bureaucratic fingers groping for any remaining dollars.

The shortage of imported raw materials had reputedly brought industrial production to less than 20 per cent of its capacity. Inflation was running at about 500 per cent a year with obvious further erosion of exports, and the Rupiah was many times over-valued. Transport and communications were in some disarray. It was later estimated that $140 millions were required to restore the railway system to its 1939 capacity. Lack of inter-island shipping was seriously affecting the movement of food such that while hunger oedema was spreading in Java stocks of maize (encouraged by the drive to substitute maize for rice in the declining diet) were rotting elsewhere in the archipelago, or being considered for export as ‘surplus stocks’. The earlier drive towards outright self-sufficiency in rice had failed, and the higher (although of questionable human digestibility) protein content of maize had led the government to aim for domestic procurements of 302,000 tons of maize in 1964. In the event only 89,000 tons could be gathered. Even where shipping was available bank credit sometimes could not be obtained for the transportation of food.

In December 1965 foreign exchange commitments were no longer met. The Central Bank found itself unable to honour cash letters of credit and suspended payment on some foreign trade credit. The prognostication was bleak: the momentum of budget deficit expansion could not be restrained without extra resources, but the inflation that stemmed from it was eroding export earnings. At the same time foreign debt servicing was peaking.

While gross government expenditure had risen about seven times between 1961 and 1964 gross receipts had risen less than five times. Therefore, the deficit was increasing as a proportion of gross receipts. Income tax, though improving, never played a role comparable to that in developed countries. Even had confrontation towards Malaysia and all development expenditure been immediately halted, the narrowing of the gap between revenue and expenditure would have depended on some rationalisation of production incentives to raise the tax-bearing capacity of production.

The impact of inflation on exports and the lagged consequence for imports can clearly be seen in Table 2.1.

TABLE 2.1

Balance of Payments: 1960-6 ($U.S. millions)

Even oil exports, emanating from an enclave industry with its own supply of foreign exchange for spare parts, declined sharply. By 1965 annual total exports were running at little more than one quarter of 1961 imports. Clearly development was not being supported by the expansion of foreign earnings. The process of deterioration in 1965 simply accelerated.

The situation could best be described by saying that the economy was locked into a downward spiral whose circumgyrations were becoming smaller and faster. Inflation had decreased incentives to produce for export and therefore the capacity to import. With a substantial proportion of government revenue coming from import duties and sales of excise taxes, the decline in imports of consumer goods and raw materials had weakened the tax-raising capacity more than if income tax had played the role it does in developed countries. Inflation, so largely caused by de...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables

- Preface

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 The Economic Crisis of 1965/6 and the Gamble Taken

- Chapter 3 Stabilisation and its Maintenance

- Chapter 4 Rehabilitation and Expansion of the Endogenous Economy

- Chapter 5 New Investment and Exogenous Growth

- Chapter 6 The Oil Sector

- Chapter 7 Disenchantment and Partial Rectification

- Chapter 8 Conclusion

- Bibliography