- 494 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Criminal Law

About this book

This title was first published in 2000: This volume includes essays on the theory and practice of criminal law. Many of the essays are interdisciplinary, reflecting the influence of developments in philosophy, sociology and psychology on the concept of criminality. Cross-cultural issues are also raised and considered.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Jurisprudential Issues

[1]

ARTICLES

A FUNCTIONAL ANALYSIS OF CRIMINAL LAW

Paul H. Robinson*

The criminal law has three primary functions. First, it must define and announce the conduct that is prohibited (or required) by the criminal law. Such “rules of conduct,” as they have been called, provide ex ante direction to members of the community as to the conduct that must be avoided (or that must be performed) upon pain of criminal sanction. This may be termed the rule articulation function of the doctrine. When a violation of the rules of conduct occurs, the criminal law takes on a different role. It must decide whether the violation merits criminal liability. This second function, setting the minimum conditions for liability, marks the shift from prohibition to adjudication.1 It typically assesses ex post whether the violation is sufficiently blameworthy “to warrant the condemnation of conviction.”2 Finally, where liability is to be imposed, criminal law doctrine must assess the relative seriousness of the offense, usually a function of the relative blameworthiness of the offender. This sets, in a general sense, the amount of punishment that is to be imposed. While the first step in the adjudication process, the liability function, requires a simple yes or no decision as to whether the minimum conditions for liability are satisfied, this second step, the grading function, requires judgments of degree. It must consider such factors as the relative harmfulness of the violation and the level of culpability of the actor.

This Article argues that these three primary functions of criminal law—rule articulation, liability assignment, and grading—are a useful way in which to analyze and organize criminal law doctrine. Modem criminal codes commonly acknowledge that criminal law serves each of these three functions. However, these same codes fail to see that a given code provision may serve one function but not another; the entire undifferentiated code is seen as serving these functions together. The Model Penal Code, for example, describes “[t]he general purposes of the provisions governing the definition of offenses” as:

* Professor of Law, Northwestern University. Earlier drafts of this Article benefitted from criticisms by Ronald Allen, Andrew Ashworth, John Donohue, Antony Duff, Dennis Patterson, and participants of law school faculty workshops at Northwestern University and New York University.

1 For a general discussion of the distinction between rules of conduct and principles of adjudication, see Paul H. Robinson, Rules of Conduct and Principles of Adjudication, 57 U. CHI. L. REV. 729 (1990).

2 This is a Model Penal Code phrase. See, e.g., MODEL PENAL CODE § 2.12(2) (1985).

[1] to forbid and prevent conduct that unjustifiably and inexcusably inflicts or threatens substantial harm to individual or public interests;

[2] to give fair warning of the nature of the conduct declared to constitute an offense;

[3] to safeguard conduct that is without fault from condemnation as criminal;

[4] to subject to public control persons whose conduct indicates that they are disposed to commit crimes;

[5] to differentiate on reasonable grounds between serious and minor offenses.3

The first two purposes appear to embody the rule articulation function, the second two the liability assignment function, and the last the grading function. Part II of this Article dissects current criminal law doctrine in terms of these three functions and demonstrates that one can identify specific doctrines as serving specific functions.

The functional differences among doctrines have not been obvious in part because the current organizing structure of criminal law uses distinctions that obscure the law’s different functions. The central organizing distinctions in criminal law doctrine have traditionally been those between offenses and defenses and between “actus reus” and “mens rea” requirements. Yet, as Part I demonstrates, each of these categories, as well as the subcategories into which they commonly are divided, contains doctrines that perform each of the three functions of rule articulation, liability assignment, and grading.

The failure of current theory and doctrine to recognize the distinctness of these functions has hurt the law’s performance of each. Parts III, IV, and V of this Article give examples of doctrinal shortcomings that may be traced to insensitivity to the distinctiveness of each function.

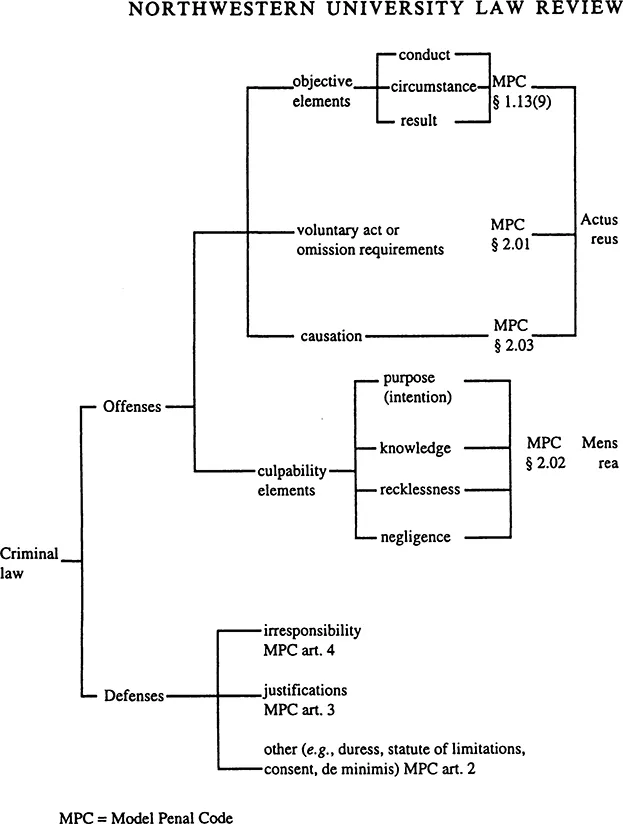

I. THE STANDARD CONCEPTUALIZATION: OFFENSES AND DEFENSES; ACTUS REUS AND MENS REA

The distinctions between offenses and defenses and between actus reus and mens rea are criminal law’s basic organizing distinctions for most lawyers, judges, and code drafters. The offense-defense distinction is reflected in the structure of modem codes. The Model Penal Code, for example, groups offenses in part II of the Code, leaving defenses for part I. The Code recognizes three kinds of defenses. Those relating to an actor’s irresponsibility, such as mental illness and infancy, are contained in article 4 of part I. Those relating to the justification of an actor’s conduct, such as self-defense and law enforcement authority, are grouped in article 3 of part I. Other miscellaneous defenses, such as duress, statute of limitations, consent, and de minimis, are included in article 2 of part I.

3 Id. § 1.02(1). The order of the subsections is altered from the original. Over two-thirds of the states have adopted a criminal code modeled to some extent upon the Model Penal Code. See Status of Substantive Penal Law Revision: Annual Report, 60 A.L.I. PROC. 560-63 (1983) (tabulating extent to which states have adopted Model Penal Code).

Modem codes also distinguish among kinds of offense elements, although they are more likely to use the modem terms “objective” and “culpability” elements rather than the older Latin labels “actus reus” and “mens rea” requirements. As for mens rea, modem codes typically follow the Model Penal Code in defining four “levels of culpability,” as the Code prefers to call them: purpose, knowledge, recklessness, and negligence.4 The remaining offense requirements typically are termed the offense’s “actus reus.” Included here are what the Code identifies as three kinds of objective elements: conduct, circumstances, and results.5 (Each of the four culpability levels is specifically defined with respect to each of the three different kinds of objective elements.)6 Also included in actus reus are the requirements of a voluntary act or an omission to perform a duty of which one is capable,7 and of a causal connection between the conduct or omission and any required result.8

To summarize, the conceptual structure of criminal law embodied in modem codes might look something like this:

4 MODEL PENAL CODE § 2.02.

5 Id. § 1.13(9).

6 See id. § 2.02(2). There are two exceptions: recklessness and negligence are not defined with respect to conduct. See id. § 2.02(2)(c)-(d); see also infra note 13 and accompanying text.

7 See MODEL PENAL CODE § 2.01.

8 See id. § 2.03. The term actus reus sometimes refers only to the voluntary act or omission requirement, sometimes to the conduct, circumstance, and result elements of an offense, and sometimes to both. See generally Paul H. Robinson, Should the Criminal Law Abandon the Actus Reus-Mens Rea Distinction?, in ACTION AND VALUE IN CRIMINAL LAW (Stephen Shute et al. eds., 1993).

Figure 1

Presumably, current doctrine uses these organizing distinctions, rather than others, because they seem more useful than others in conceptualizing and analyzing criminal law. Let these distinctions, then, be the starting point for describing how different doctrines perform different functions.

One might initially estimate that the actus reus requirements define the prohibited conduct, the rule articulation function, and that the mens rea requirements, with the help of the general defenses, define the minimum requirements of liability for a violation, the liability function. A closer examination, however, suggests that the functional structure of current criminal law is somewhat different.

A. “Actus Reus” Requirements

The conduct and circumstance elements of offense definitions do contribute to the definition of the prohibited conduct, the rule articulation function, but result elements do not. Unlike conduct and circumstance elements, result elements are not necessary to define the prohibited conduct. The criminal law must prohibit an actor’s conduct, not the conduct’s result, because the law can influence only the actor’s conduct. The law may claim to prohibit a particular result; however, the law actually means to claim that it prohibits actors from engaging in conduct that would bring about (or risk bringing about) that result. An actual resulting harm may make the violation more serious, some would argue, but the fortuity of whether the result actually occurs does not alter the nature of the conduct that constitutes the violation. The conduct remains objectionable notwithstanding the happenstance that the result does not occur.9 Result elements, then, serve only to aggravate an actor’s liability, the grading function.

Similarly, the causation requirement—defining the relation between an actor’s conduct and a result that will give rise to an actor’s accountability for the result—serves the grading function, not the rule articulation function. Like the requirement of a result, the causation rules determine when an actor’s liability is to be aggravated because the actor is accountable for a harmful result. Because result elements and causation requirements are not necessary to define the conduct prohibited by the criminal law, it is not surprising that liability does not necessarily depend upon them. If a prohibited result does not occur or if a required causal connection is not established, the actor frequently is liable for a lesser offense, such as an attempt.10

Many of the omission and possession rules, which impose liability for an omission to perform a legal duty or for possession of contraband even in the absence of an affirmative act, contribute to the criminal law’s definition of the conduct that is prohibited and required. Without the special duty requirements or the special prohibition for the possession of contraband, the law would not provide a complete description of what is acceptable and unacceptable conduct. Thus, aspects of the commission, omission, and possession rules serve the rule articulation function. However, other aspects of these actus reus rules do not serve the rule articulation function. The voluntariness aspect of the act requirement, the “physical capacity to perform” requirement of the omission doctrine, and the requirement in the possession liability rules that the actor know of his possession for a period sufficient to terminate the possession, do not define prohibited conduct. Rather, those requirements define minimum conditions for holding an actor condemnable for a violation by commission, omission, or possession, respectively. The rules of conduct continue to prohibit possession of certain drugs, even if the possessor of the drug is held nonliable because he did not know of the possession for a period sufficient to terminate it. Filing an income tax return remains a duty, although the nonfiling actor is not punished if it was physically impossible for her to file. In other words, the actus reus requirements of voluntariness, capacity, and knowledge of possession serve a liability function in the same way that many mens rea requirements do. For example, under the mens rea requirements, taking another person’s property without permission remains a violation of the rules of conduct although the actor is held nonliable for such a taking where he was unaware of a risk th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Series Preface

- Introduction

- Part I Jurisprudential Issues

- Part II Doctrinal Issues: The Limits of Responsibility

- Part III Punishment

- Name Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Criminal Law by Thomas Morawetz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.