![]()

1

Outline of the Study

OBJECTIVES

In industrialising, most countries first acquire technology. Before production can begin, even before plants can be constructed and equipment installed, a minimal amount of information about the manufacturing technique must usually be imported. Up to the time of transfer, this information will reside in patents and other published documents, in blueprints, in design and operators’ manuals that are the private possession of construction and producing firms abroad, and in the accumulated experience of individuals who have perfected the technique. The reservoirs of technological knowledge are many, deep and distant.

Yet, somehow or other, the fluid that resides in these distant sources must be tapped, and piped as swiftly and economically as possible to the potential users in the developing countries. Moreover, as a fluid to be supplied by one group of individuals and acquired by another group of individuals, technical knowledge is very complex, so complex that its nature is difficult to define and its transfer to describe. To categorise technological knowledge and to investigate its transfer from developed countries to the Republic of Korea are two of the objectives of this study.

It might be said that attaining these two objectives would be sufficient to justify carrying out the study, for relatively little is known about what constitutes technological knowledge and about how this knowledge is drawn upon; but the choice of the Republic of Korea provides further justification. By general agreement, the Republic of Korea has been particularly successful in industrialising: it therefore should be able to provide not only a case study of the transfer of technology — i.e. a description — but also an inquiry into how the transfer can be conducted skilfully — i.e. a prescription.

It is unlikely that Korea’s achievements would have been so great had its acquisition of modern technology been slow and inefficient; so the presumption can be made that the transfer of technology to the Republic of Korea has been relatively smooth. Nevertheless, this general statement is not very revealing; it immediately leads one to ask in which activities, involved in the transfer, Korea may have excelled and in which not. It also leads one to ask fundamental questions concerning the relations between the acquisition of technology on the one hand and the production of goods on the other hand and the meaning of excellence. Economists have reasonably good ideas of what is meant by excellence in production and exchange, centring on efficiency in the static sense and on innovation and responsiveness in the dynamic sense, but they have few ideas of what is meant by excellence in the transfer of technological knowledge. In the observation of what one imagines to have been a successful transfer some ideas may emerge; to evoke these ideas is the final aim of this study.

MEANS EMPLOYED

The chief means employed in trying to meet the aims of this work were detailed case studies involving the recent acquisition of sophisticated technical knowledge by Korean companies. The historical period involved is the recent past, extending from the mid-1960s to the present; the technologies involved are chemical, metallurgical and mechanical. The sources of the technological knowledge were firms in the developed countries, specifically the United States, Japan and West Germany; the firms that utilised the imported techniques are scattered about Korea.

The choices of firms located in a developing country and owned by its citizens, of advanced products and precisely defined manufacturing techniques and of extremely detailed inquiries, were deliberate. Already there have been several studies published on the transfer of technology by the vehicle of multi-national firms (Baranson [1978], Berman [1976] and Teece [1976]), so it seemed proper to concentrate on transfers to independent firms domiciled within a developing country. The advantages of applying simple techniques utilising resources abundant in the developing countries have been eloquently argued and illustrated (see Stewart [1978], and the references cited therein), so it seemed useful to concentrate on the sophisticated techniques that developing countries themselves are determined to introduce. Last of all, those studies that have been made of the acquisition of advanced technologies by developing countries, chiefly Korea, have summarised the experience of many firms in selected industries (machinery in the cases of Kim, Lin-Su and Kim, Young-Bae [forthcoming], and Ausden and Kim [1984]; and electronics in the cases of Kim, Lin-Su [1980a], Kim, Lin-Su [1980b] and Kim, Lin-Su and Utterback [1983]), achieving broad coverage but not describing the technologies acquired, so it seemed desirable to fill this gap. Technologies are so complex that to consider more than a few would be impossible for a limited number of researchers; as it was, our investigation of the acquisition of four technologies occupied our attention over a period of ten years. To have drawn a larger sample would have taxed us beyond our ability to cope, and would also, in all likelihood, have taxed the capacity of the reader of this book to absorb.

The Korean firms that acquired the technologies provided our chief fund of information. Other sources ranged widely, from government ministries and international agencies, through academic publications, manuals for engineers and businessmen, to promotional material. The academic literature appears in four overlapping fields commonly designated as ‘technology transfer’, ‘appropriate technology’, ‘the multi-nationals’ and ‘science policy’. Where the material is germane, it will be referred to, but there will be no general attempt to survey the literature.

It may well be that the main contribution of this work on the acquisition and application of modern technology by the Republic of Korea will lie not in the objectives attained but in the information secured. In conducting the case studies the investigators were given almost complete access to all the material in Korea, thanks to the generosity of the private firms and the Korean government. Economic data on costs and prices; financial data on sources and uses of funds; personal data on backgrounds and employment; institutional data on negotiations and agreements; and general technical data on products and processes were made available in detail whenever they were requested. The only data withheld were engineering specifications and operating conditions for proprietory processes and products.

Not only were data willingly provided, but they were the correct data, so far as we have been able to ascertain. In most developing countries, those who do economic research encounter information which they become accustomed to examine with great care. Our scrutiny of the information we gathered in Korea did not reveal any inconsistencies: it was, to the best of our knowledge, accurately recorded and honestly reported. We have consequently worked with it with confidence.

The long chapters forming the core of this study reveal the information that was gathered and the analysis that it permitted. The import of modern, sophisticated technologies into a developing country provides a challenge to its engineers and managers, a challenge which we presumed, at the start of our project, had been successfully met. To test this hypothesis of successful incorporation of technologies we needed much information; hence the concentration on relatively recent events, which have been recorded in greater detail and in more accessible sources.

The industries from which our cases are drawn are petrochemicals, iron and steel, heavy engineering goods and textiles. In the first three of these industries, as in most other industries in Korea utilising imported technologies, the manufacturing process is employed by a single firm which has been granted a monopoly in its use by the government. The study of the adoption of the technology is therefore almost synonymous with the study of the firm that adopts it.

Surrounding the core of the study are four other chapters; preceding it are an attempt to provide a framework within which case studies of technology can be systematically carried out (Chapter 2 on methodology) and a description of the broader economic environment within which the technologies were absorbed (Chapter 3). This third chapter presents material on the overall growth of the Korean economy and of the growth of those four industries from which the case studies were drawn. Following the case studies are a summary of the experience of Japan, a forerunner in the import of the technologies (Chapter 8), and a final chapter (9) that draws conclusions.

![]()

2

Methodology

DEFINITIONS

The purpose of this chapter is to describe the methodology that has guided the four case studies on the adoption and diffusion of imported technology in Korea. Certain parts of the methodology — the objectives, the definitions of terms and some of the quantitative measures and relevant statistical tests — were formulated well before the case studies were begun; other parts — the sources of information, the division of research efforts, many of the hypotheses and the theoretical underpinnings — were revised after the first impressions from the industrial visits had been gained. In the natural sciences, experiments can be designed before laboratory work commences; in the social sciences, design and data collection proceed together.

The objective of this enquiry has been to learn as much as possible about the adoption and diffusion of industrial technologies imported into the Republic of Korea from more advanced economies. Such questions were asked as: what techniques were available, and which one was chosen and why? Through what agency was the technology transferred? Which individuals, with which skills, of which nationalities and with which affiliations, were involved? How rapidly and efficiently was the technology absorbed? What changes were made in the process and why? What improvements were subsequently made: by whom and with what consequences? How are all these phenomena related to Korea’s economic development?

Common to the case studies were not only a set of questions to be answered but also a vocabulary. It is this vocabulary to which attention will first be directed. Of the terms used, the broadest is the word adoption, which will signify for us all that takes place, between the time the matter of a technology is first broached and the time when it has been mastered by Korea. Adoption implies, as transfer does not, that events are being considered from the vantage-point of the developing country. Such a vantage-point was almost forced upon us, because our research was done in a developing, not a developed country, drawing upon the information available there; but it is also voluntary, because it is the developing country’s interest that we had at heart. Transfer as a word is neutral, whereas we are prejudiced on the behalf of the recipient.

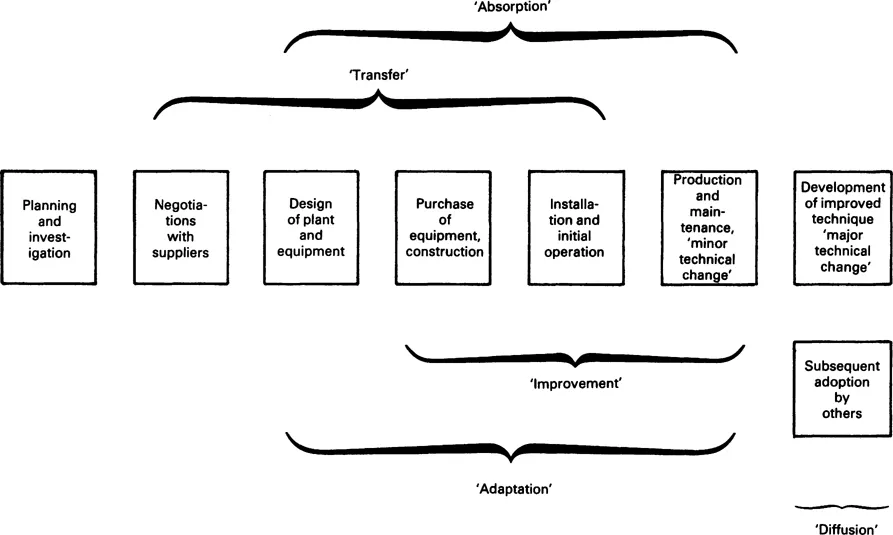

We will define all the terms below, but refer first to Figures 2.1 and 2.2 in which the majority are displayed. The two figures are complementary; both start with the same event (industrial planning) and both portray the same sequence of events. The difference between the two figures is that Figure 2.1 focuses on the activities that take place, whereas Figure 2.2 focuses on the major decisions that follow each activity. Thus the first activity in the sequence, ‘Planning and Investigation’, leads to the choices of what technology is to be employed, what products are to be manufactured, what scale of operation is to be selected and to what structure the producing industry is to conform. The reason for splitting activities from decisions or choices is that some of the terms to be defined refer chiefly to the activities that are undertaken within the developing country while other terms refer chiefly to the decisions that are made. To take as an illustration the term that has’ been used already, adoption, it is meant to cover the sequence of decisions or choices from the first activity to the last, inclusive; it therefore appears in Figure 2.2.

The definitions are:

(1) Adoption: The entire sequence of decisions made within the developing country determining how, when, where and with what consequences an imported technology is to be employed. The term is employed in a manner similar to the adoption of a child, in which the child is selected by the husband and wife, legal requirements are fulfilled specifying the rights and duties of all three, and the child is subsequently raised by its new parents. The course of adoption ends when the child becomes self-sufficient.

(2) Transfer: Once foreign suppliers of the technology are approached, the transfer is said to begin. Transfer is complete when the importing country has carried out all the activities necessary to commence production.

Figure 2.1: Flow diagram illustrating activities in process of incorporating foreign technology

Figure 2.2: Flow diagram illustrating major decisions

(3) Technology: A distinction will be made between techniques of production and technology. Technology is defined as the general knowledge or information that permits some tasks to be accomplished, some service rendered, or some products manufactured.

(4) Technique: Technique is defined as the knowledge necessary to design and operate the specific plant and equipment used in production.

(5) Techn...