![]()

Gender stereotypes in advertising: a review of current research

Stacy Landreth Grau and Yorgos C. Zotos

The purpose of this paper is to highlight the historical context of gender stereotypes in advertising and then examine the scholarship related to gender stereotypes. Gender portrayals in advertising have been examined extensively in the last five decades and still remain an important topic. Changing role structure in the family and in the labor force has brought significant variation in both male and female roles and subsequently how it is reflected in advertising. It has been noted that there is a culture lag. Sexes for a long period of time were depicted in advertising in more traditional roles. Women were presented in an inferior manner relative to their potential and capabilities, while at the same the data indicated a shift towards more positive role portrayals. The changing role of men is the area that has seen the greatest interest in the past few years. Men are depicted in advertising in ‘softer’ roles, while interacting with their children. Men are also shown in more egalitarian roles. The paper finally attempts to outline the future research direction of gender portrayals in advertising. First, research should focus on examining gender portrayals in online platforms, and find ways to modify current coding schemes to digital formats. Second, companies and the media are beginning to pay attention to a once largely ignored segment the lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgender (LGBT) consumer. Third, recent advertising has focused on the ‘empowered’ women called femvertising.

Introduction

Scholars have been interested in stereotypes – particularly of women – in advertising for more than 50 years. In that time, researchers have been interested not only in the ‘what’ (e.g., what stereotypes are used to portray women and men) but also the ‘why’ (e.g., the cultural implications of using stereotypes and advertising and the ‘now what’ (e.g., the social consequences of stereotypes and advertising (Hawkins and Coney 1976; Lundstrom and Sciglimpaglia 1977; McArthur and Resko 1975). The purpose of this paper is to examine research in this area since 2010 and provide direction for the next five years in a fragmented media environment.

Stereotypes are beliefs about a social category (Vinacke 1957) especially those that differentiate genders (Ashmore and Del Boca 1981). Stereotypes become problematic when they lead to expectations about one social category over another or restrict opportunities for one social category over another. Over the years, several content analyses have examined components such as physical characteristics (e.g., body size, height), occupational status, roles (e.g., leadership) and traits (e.g., self-assertion). Research has shown that women are generally presented in more decorative roles (e.g., for their beauty or body), in more family oriented roles, in fewer professional roles and in more demure roles (Uray and Burnaz 2003) while men are typically shown as more independent, authoritarian and professional with little regard to age and physical appearances (Reichert and Carpenter 2004).

That said, there is still much to be learned about the changing role of gender representations in advertising. This introduction to the International Journal of Advertising’s special issue on Gender Stereotypes in Advertising highlights some of the historical context of gender stereotypes in advertising and then examine scholarship related to gender stereotypes since 2010 to identify the current key areas being studied.

Gender stereotypes in advertising

Gender stereotypes in advertising is a topic with more than five decades of related research. The outcome of literature was ignited by social and historical contingencies. First, the rise of feminism in the 1960s challenged equal opportunities for men and women and initiated a gradual change in occupational opportunities and domestic structures (Zotos and Lysonski 1994; Plakoyiannaki et al. 2008; Plakoyiannaki and Zotos 2009; Zotos and Tsichla 2014) especially for women. Second, changes in the labor force brought significant variation in both male and female roles and subsequently how they are reflected in advertising (Zotos and Lysonski 1994; Zotos and Tsichla 2014). Third, the changing role structure in the family has created significant variations in the female role (Zotos and Lysonski 1994) and more recently the male role. During these years, women were presented in an inferior manner relative to their potential and capabilities, while at the same time the data indicated a slow shift towards more positive role portrayals. Past literature (Lysonski 1985; Corteze 1999; Kilbourne 1999; Lazar 2006; Plakoyiannaki and Zotos 2009) has proposed that advertising contributes to gender inequality by promoting ‘sexism’, and distorted body image symbols as valid and acceptable. Since then, women’s roles have undergone dramatic changes and there have been changes in portrayals as well.

The ‘mirror’ versus the ‘mold’ debate

There is a long-lasting debate between advertisers and sociologists, about the role and the social nature of advertising, especially when it comes to stereotypes within advertising. Two opposing points of view have been developed – the ‘mirror’ versus the ‘mold’ argument. Following the ‘mirror’ point of view, advertising reflects values that exist and are dominant in society. Furthermore, this view suggests that the best that advertising can succeed to do is to act as a magnified lens, which offers an extrapolated picture of a social phenomenon (Pollay 1986, 1987). A possible interpretation of this argument suggests that in the contemporary socioeconomic and political environment, which influences the value system of a society, multiple factors are interfaced and interrelated. Therefore, the impact of advertising is not valued as being significant. Hence the way that women and men presented in advertising would follow the dominant concepts held regarding gender roles (Zotos and Tsichla 2014).

In contrast, the ‘mold’ point of views advertising as a reflection of society and its prevailing values (Manstead and McCulloch 1981; Pollay 1986, 1987). Cultivation theory suggests that peoples’ perception of social reality is shaped by the media (Gerbner 1998). They incorporate stereotypes presented by the media into their own system of values, ideas, and beliefs about the quality of life (Zotos and Tsichla 2014). They start creating a concept of reality, which tends to match the advertised images. At the end of a long process, individual behavior and human beings relationships are formulated in such a manner that could be characterized as a ‘hybrid.’ Advertising’s impact is a crucial factor, which contributes to the development of this ‘hybrid.’ It is accepted the gender representations are socially constructed. According to this viewpoint, advertising campaigns create gender identity, based on their images, the stereotyped iconography of masculinity and femininity (Schroeder and Zwick 2004).

Based on the aforementioned analysis, it could be suggested that the ‘mirror’ and the ‘mold’ argument is a continuum. The real life examples lie in this continuum according to the social values which are promoted, and the type of the advertised products (Zotos and Tsichla 2014). Accepting advertising as a system of visual representation, which creates meaning within the framework of culture, it seems that reflects and contributes to culture (Hall 1980; Albers-Miller and Gelb 1996; Zotos and Tsichla 2014). To grasp these ideas in an integrated manner, this long-lasting debate between the ‘mirror’ and the ‘mold’ argument should reflect Kilbourne’s (1999, 57–58) statement: ‘Advertising is our environment. We swim in it as fish swim in the water. We cannot escape it… advertising messages are inside our intimate relationships, our home, our hearts, our heads.’

Gender stereotypes in advertising: recent research since 2010

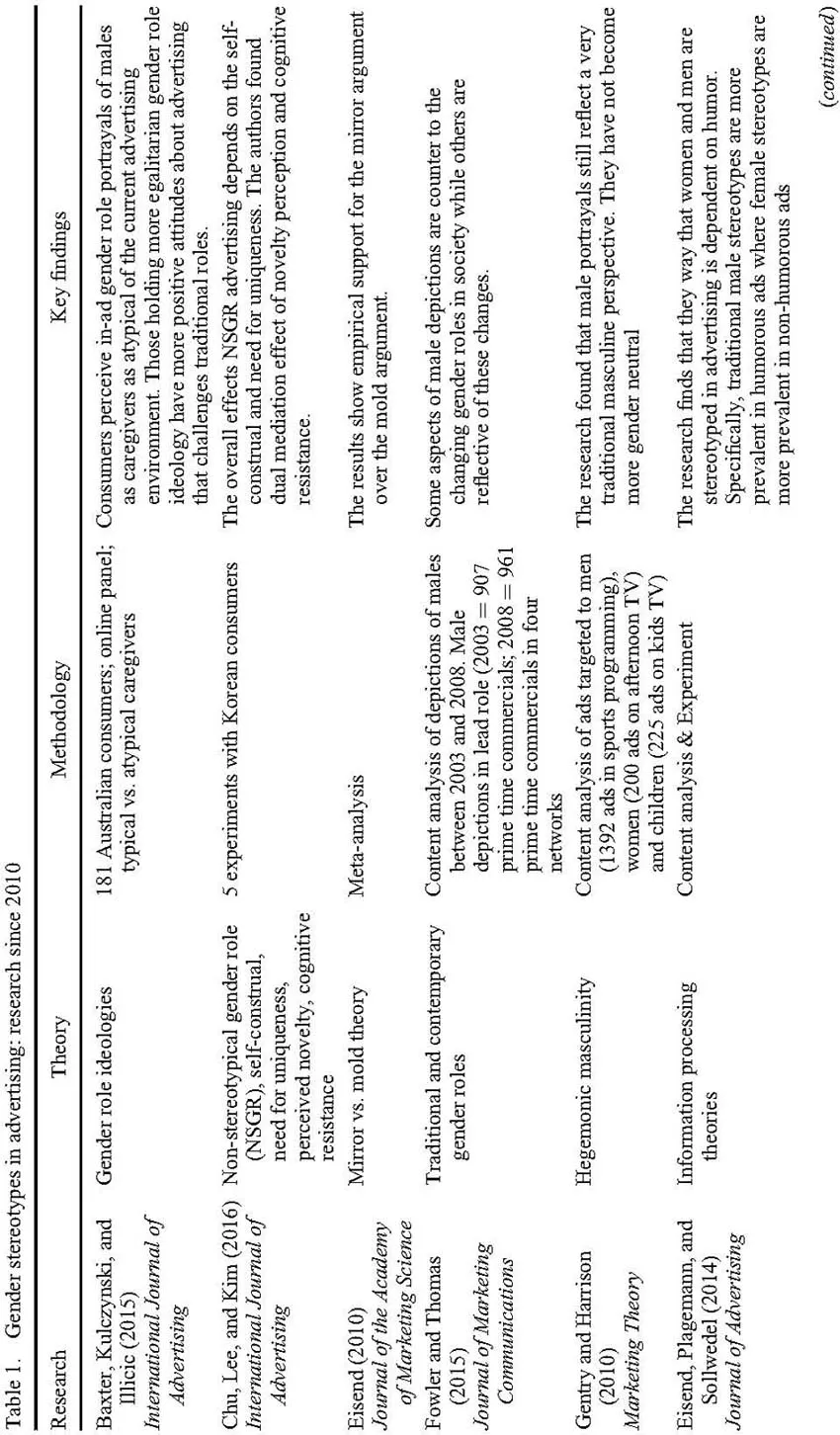

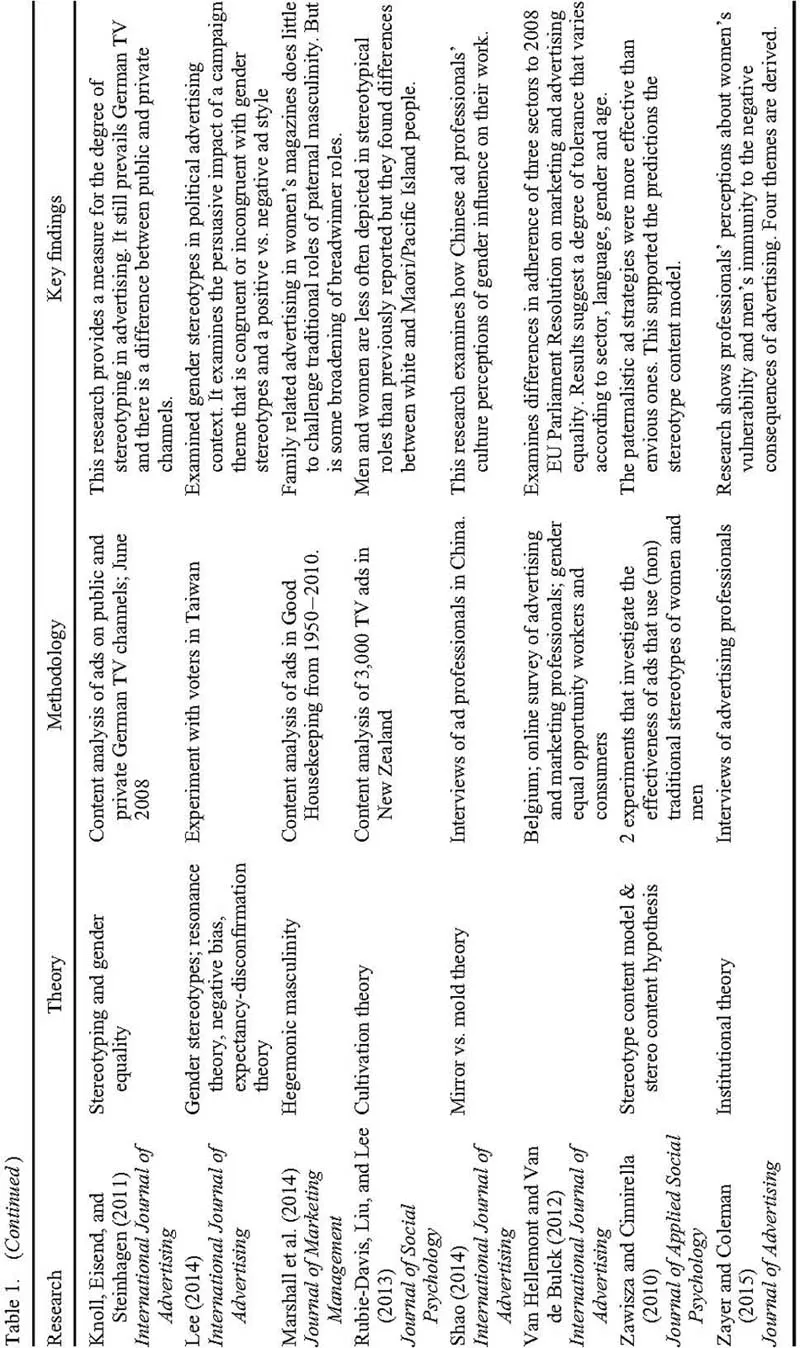

Despite the fact that gender stereotypes in advertising have been studied for many years, the past six years have seen a robust addition to the literature. We highlighted research found in four key advertising journals: Journal of Advertising, International Journal of Advertising, Journal of Current Issues in Research in Advertising, and Journal of Advertising Research as well as other marketing communications journals. Several important themes emerged (see Table 1).

Updated trends and directions

Recent research shows that, in general, gender stereotyping in advertising still exists and is prevalent in many countries around the world. Eisend (2010) set out to explore the degree of gender stereotyping as well as any changes over the years. The primary contribution of his work is to provide a quantitative review of 64 studies in a meta-analysis on the effects of gender stereotypes in advertising. He found that some stereotyping still persists – particularly for women. Occupational status still showed the highest degree of stereotyping, despite the education, occupation and status changes earned by women over the past several years. Interestingly, Eisend (2010) also found that the degree of stereotyping has decreased over the years due mostly to improvements in high masculinity societies (such as Japan). There was no substantial decrease in low masculinity societies like Sweden.

Knoll, Eisend and Steinhagen (2011) developed a new way to measure the degree of stereotyping in advertising. They found that gender stereotyping was still prevalent in German television and that this stereotyping depends on the type of channel (public vs. private channels). Across both types of channels, Knoll et al. (2011) found that women were more likely to be younger and depicted as product users with domestic products and more likely to be portrayed at home in dependent roles. Men were more likely depicted as authoritarian and older and are more likely to be portrayed outside of the home in independent roles. These findings are in line with other studies of several other cultures. However, on public channels, stereotyping was higher for variables like role and location as well as occupational status. On private channels, stereotyping relates more to role behavior and physical characteristics. The results of stereotyping were not limited to the USA and Europe. Work by Rubie-Davies, Liu, and Lee (2013) found that in their examination of television advertising in New Zealand men and women were less often depicted in stereotypical roles than in the past. This research suggests progress in stereotyped portrayals in the country.

There are caveats to the consequences of stereotyping. Eisend, Plagemann, and Sollwedel (2014) found that while stereotyping does exist in advertising, consumer’s perceptions about it might be less serious than expected. They examined the role of humor in advertising and its relationship to gender stereotyping. They found that gender role portrayals are less serious if they are used as sources of humor. Specifically, male stereotypes are more prevalent in humorous ads, while female stereotypes are more prevalent in non-humorous ads. This points to the influence of other variables in determining the ultimate effects of stereotypes in advertising that require additional examination. It is important to continue to track changes in gender stereotypes in advertising and examine factors that could affect consumers’ reactions to these portrayals.

View from practitioners

Advertising professionals are often considered ‘cultural intermediaries’ (Cronin 2004) who develop messages. And yet their decision making process about gender portrayals in advertising campaigns is barely considered. Despite Grow’s (2008) call for more research, little has been done on the ‘gendered voice of advertising’ until the past two years. Shao (2014) examined Chinese advertising practitioners and how Chinese culture impacts advertising creation. In terms of similarities and differences, Chinese advertising depicts males in more occupational and recreational roles whereas women were depicted in more decorative roles (Cheng 1997). However, Johansson (1999) found that Chinese advertising depicted women as shy and subordinate compared to stronger roles for women in the USA. But in general there are more similarities than differences in how women and men are depicted in China compared to other societies. In 26 interviews with advertising professionals, Shao (2014) found that Chinese advertising professionals do not reflect on their role in perpetuating stereotypes, claiming that they mirror reality rather than representing or distorting it. They claimed that they were simply reflecting Chinese culture.

Zayer and Coleman (2015) examined advertising professionals’ perceptions of how gender portrayals impact men and women and how these perceptions influence their strategic and creative decisions. Using institutional theory as a foundation, the authors provide a more holistic viewpoint of advertising ethics. Their interview respondents claimed they also mirror the dominant viewpoints of society regarding gender stereotypes but point out that men are not immune to the gender stereotypes and call for more research on the negative impact of gender stereotypes of men in advertising as well.

Few studies have examined advertising that is viewed as unfriendly towards men or women by other stakeholders. Van Hellemont and Van de Bulck (2012) examined the views of advertising professiona...