![]()

Part I

Urbanisation, poverty, food and measurement

![]()

1 African urbanisation and poverty

Muna Shifa and Jacqueline Borel-Saladin

Introduction

Current trends and projections of urban growth have led to increased recognition of the importance of cities. The New Urban Agenda (NUA) refers to urbanisation as “one of the 21st century’s most transformative trends” (United Nations General Assembly 2016: 3). Notably, the Agenda recognises the unique urban developmental challenges in developing and least developed countries – especially in Africa – and calls for special attention to be paid to them. This emphasis on African cities seems necessary, given the longstanding perception that Africa is experiencing an “historically rapid rate of urbanisation” (AfDB/OECD/UNDP 2016). By some estimates, the share of urban residents grew from 14% in 1950 to 40% today, with the figure expected to reach 50% by mid-2030. Despite this, both the extent of urbanisation and the relationship between urbanisation and development in Africa are still hotly contested. In this chapter, we will discuss how and why this contestation has developed. We will begin by discussing how development, economic growth, and urbanisation are defined and then consider the relationship between them. This then leads to a discussion of the conflicting evidence for this relationship in Africa. The existing body of research on this relationship has focused predominantly on large African cities. This, however, means that there is a knowledge gap regarding smaller African cities, which is concerning, considering their growing importance as sites of urbanisation in Africa. It is therefore for this reason that the research of the Consuming Urban Poverty (CUP) project focuses on food security and poverty specifically in the context of secondary African cities.

Defining development and urbanisation

The term “development” is often assumed to refer to economic development only; however, broader conceptualisations of the term consider more than just economic growth as measured by Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Scutaru 2013). These variables include unemployment, poverty, education, health, environment, migration, overcrowding, and inequality. One of the best known of these more comprehensive indicators is perhaps the Human Development Index (HDI), which measures health by life expectancy at birth, education by mean of number of years of formal schooling, and standard of living by Gross National Income (GNI) per capita. When focusing on the economic growth aspect of development, it is important to remember that simply increasing GDP or GNI does not necessarily lead to development. Inclusive growth is required, that being a long-term, sustainable approach to economic growth, with equal opportunity for a large part of the labour force to access markets and resources (Ianchovichina and Lundstrom 2009). This type of economic growth is essential to poverty reduction.

Defining urbanisation is complicated by several factors. In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), different criteria are used for defining urban areas, ranging from population size to the main economic activity and government function (Cohen 2004; McGranahan and Satterthwaite 2014). Differing types of boundaries for an urban area further confuse the issue (for a discussion on data-related issues, see Chapter 4 and Borel-Saladin (2017a, 2017b)). Some researchers argue that more accurate measurement can be achieved by focusing on the economics of urbanisation (Potts 2017). Taking this approach, the main marker of urbanisation would be a change in economic activity, i.e. residents no longer predominantly engaged in agricultural activity to survive but employed in industry and tertiary sectors. However, some argue it is not feasible to add economic criteria to the definition of “urban” currently employed in most of Africa for several reasons (Turok 2017), one being that economic data at the sub-national scale is even less reliable and more patchy than population data. Complicating the definition of urban areas with an economic dimension would therefore jeopardise further the already infrequent and uneven collection of important basic demographic information. In addition, the data collected for the newly defined urban areas would be difficult to compare to historical data due to lack of consistent information for earlier periods.

Another argument regarding the definition of urbanisation proposes that the spatial-demographic conceptualisation of urbanisation cannot simply be ignored in favour of an economic conceptualisation as large, concentrated groups of people have different needs to rural areas regardless of the dominant type of economic activity taking place, e.g. different infrastructure (Fox et al. 2017). In addition, it is suggested that using the traditional multiple census and survey data sources, combined with remote sensing and migration studies over long periods, can help refine the accuracy of urban population estimates. There are also some promising developments using geospatial datasets which combine remotely sensed data and census data with innovative modelling techniques, e.g. the Global Rural–Urban Mapping Project (GRUMP http://sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu/data/collection/grump-v1), the Atlas of Urban Expansion (Angel 2012), WorldPop (www.worldpop.org.uk/), and Africapolis (www.oecd.org/swac/topics/africapolis/).

The terms “urbanisation” and “urban growth” are also often used interchangeably. These terms are not synonymous, however, as “urbanisation” refers to an increasing proportion of the total population living in urban areas, while “urban growth” refers to the absolute growth of the urban population. The perceived interchangeability of these terms is thus particularly problematic when referring to SSA where urban population growth rates are high but urbanisation rates are historically low (Fox et al. 2017). “Urban expansion” (which refers to the physical expansion of urban areas) is another term often used to mean increased urbanisation, yet the physical area occupied by an urban settlement may increase without population growth (resulting in declining population densities), or the population may increase without an increase in the size of the area occupied (resulting in increased densities).

Several scholars argue that natural population increase rather than net rural–urban migration might be the major driving force for the observed rapid urban growth in Africa (Kessides 2007; Potts 2012b; Parnell and Pieterse 2014; Fox et al. 2017). Many African cities have in the past, and continue today, to grow quickly, with population growth rates faster than those of European cities during the height of their expansion in the 19th Century (Potts 2012a). However, technically speaking, for urbanisation to occur, the urban population growth rate must exceed the national growth rate, and in African cities most urban population growth patterns generally tend to follow national population growth patterns. Nevertheless, the populations of many African countries have been growing fast (Potts 2012a). Improved technology and disease control resulting in access to surplus food supplies and reduced mortality are believed to have contributed significantly to this rapid population growth in African cities since 1960 (Fox 2012). High fertility and low mortality rates in rural areas have also resulted in rural settlements reaching the population threshold to be reclassified as urban areas (Fox et al. 2017). Growing populations in rural areas with limited resources may also create a push to urban areas.

That being said, each African city still has its own unique history and path of development. This includes migration patterns that are complex and responsive to multiple factors, with people migrating for a variety of different reasons over time (Oyeniyi 2013). Understanding and measuring these migration flows is obviously important for accurately gauging urban population size and change; however, the longstanding assumption of sustained, uniformly high levels of rural–urban migration across the African continent is increasingly being challenged. The reclassification of rural areas as urban areas has, for example, probably contributed more to urbanisation in SSA than it has been credited with, and rural–urban migration less so (Fox et al. 2017). Thus, continued high levels of urban population growth and the complications this entails remain a very real issue in SSA.

Urbanisation, economic growth and poverty reduction

One of the ways cities are considered to drive development is through economic growth, yet this view takes for granted the built-in positive relationship between urbanisation and growth (Turok and McGranahan 2013). Instead, it is the specific form of urbanisation that determines if it enables growth. As such, in some cases the concentration of people and businesses in cities can facilitate economic growth by increasing productivity through the effects of specialisation and scale (Collier 2016), which in turn can allow increased efficiency from large-scale, specialised production, the reduction of transaction costs, and the sharing of knowledge among firms – the so-called agglomeration economies (Turok and McGranahan 2013). However, this pooling of people and business activities in cities does not necessarily guarantee increased economic growth.

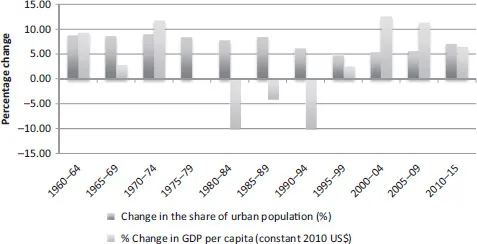

Although economic growth and urbanisation are positively related in the context of other developing regions, the evidence is mixed in the case of Africa. Several studies have found no positive relationship between urbanisation and economic growth or development in Africa (Bouare 2006; Bloom and Khanna 2007; Ravallion et al. 2007; Brückner 2012; Turok 2013; Gollin et al. 2016). Bouare (2006) even found a negative correlation between urbanisation and GDP for 23 of 32 SSA countries between 1985 and 2000. Likewise, Turok (2013) found no relationship between urbanisation levels and levels of GDP per capita for selected African countries over the period 1985–2010. However, in contrast, using the HDI as a measure of development, Njoh (2003) found a positive relationship between urbanisation and development in 40 SSA countries. Likewise, Kessides (2007) found a positive relationship between urbanisation and economic growth in 15 of the 24 countries considered between 1990 and 2003. However, the same study showed a negative relationship between GDP and urbanisation for the remaining nine countries. Potts (2016) argues that though some of the findings of these studies could be due to significant variations in annual growth of GDP per capita in most African countries in the 1980s and 1990s, that could not be adequately captured by the few data points used. The significant fluctuations in GDP per capita growth in SSA can be seen in Figure 1.1, which presents growth in levels of urbanisation and GDP per capita in SSA based on five-year intervals.

Figure 1.1 Percentage changes in the share of population and GDP per capita in SSA between 1960 and 2016

Figure 1.1 shows that SSA countries registered higher economic growth over the period 1960–1975. Rapid urbanisation also occurred in this period across the continent. This was mostly a response to the lifting of influx control measures imposed by colonial governments, which had previously limited migration to many African cities (Satterthwaite 2007). Strong economic growth from the 1960s and concomitant investment in, and development of, urban areas also supported increased rural–urban migration (Potts 2012a). Economic growth during this period was driven mainly by both high resource exports and structural transformation (Jedwab 2011; De Vries et al. 2015). For instance, using data from 11 countries, a recent study showed that manufacturing’s employment share grew from 4.7% in 1960 to 7.8% in 1975 (De Vries et al. 2015). These structural changes, which resulted in the re-allocation of workers from agriculture to urban sector jobs in manufacturing and service sectors also contributed to the increase in rate of urban growth. Thus, although part of the initial increase in urban growth in Africa was due to the relaxation of migration laws after independence in many countries, evidence suggests that economic growth and the associated structural transformation also played a role (Weeks 1994).

After 1975, however, there is disagreement about the rate of urbanisation in SSA countries (Potts 2006, 2009, 2012b; Satterthwaite 2010). This is because the lack of up-to-date, reliable census data led to international organisations and researchers relying on population predictions based on the earlier period of rapid urbanisation. Concurrently, SSA countries registered slow or negative economic growth over the period 1975–1995, attributable to various economic and political crises (e.g. oil crises, ethnic conflict, and war) and the regulations around structural adjustment programmes to which many African countries were subjected. The result was the widely held belief that SSA countries continued to urbanise rapidly throughout the 1980s and 1990s despite low levels of economic growth (Satterthwaite 2010). This has been held up as a stark contrast to the positive association between urbanisation and economic growth found in most developed countries, leading to the long-held belief that urbanisation occurred without economic growth in Africa (United Nations 2015).

As stated, however, this premise has been challenged with the argument that urbanisation in most of SSA was either very slow or stagnated in the 1980s/1990s (Kessides 2007; Potts 2006, 2009, 2012b; Satterthwaite 2010). Potts (2008) argues that rural–urban migration decreased in the face of less spending on urban areas, due to the oil crisis and structural adjustment programmes that led to slowing economic growth in this period. Figure 1.1 confirms this, as it illustrates how urbanisation also started slowing down after 1975 and declined significantly in the 1990s. Increasing circular migration and shorter periods of time spent in towns countered the flow of rural–urban migrants leading to a decline in urbanisation in SSA following the weakening of African economies since the 1980s. As Potts (2012b: 14) states, “confronted by economic insecurity and other hardships worse than where they came from, people behave as rationally in Africa as anywhere else”, and left the urban areas.

Although economic growth in SSA started to recover after 1995, the percentage increase in urbanisation increased modestly. In addition to natural urban growth, oil discovery in several SSA countries may have also contributed to the increase in the level of urbanisation in recent years (Potts 2013). More recent data show that some African countries experienced increased urbanisation with GDP growth from 2003 to 2014, thanks to strengthening commodity prices (Potts 2017). Still, continued high rates of urbanisation have been incorrectly assumed in some countries. There are also variations in the level of urbanisation in different regions of Africa over time. For instance, looking at the countries in the CUP project, the urban share of the population increased far more in Zambia than in Kenya and Zimbabwe between 1950 and 1980 (Figure 1.2). Zambia’s urban population increased by more than 200% during this period, and then declined by 12% between 1980 and 2000. The comparison of urbanisation and per capita GDP over time in Figure 1.3 shows that this de-urbanisation occurred mainly in response to economic decline after the 1980s (Potts 2006). A similar pattern of decline in urban population share and GDP is observed in Zimbabwe since 2000. Zimbabwe, subject to continuous, long-term political conflict and its negative economic consequences, was the only one of the three countries in the CUP study to experience a drop in the proportion of its urban population between 2000 and 2015. There is a general upward trend in the share of the urban population in Kenya, but a decline in the rate of growth post 1980, mirroring the lower annual GDP growth rates from that point onwards. Thus, the notion that SSA countries urbanised without economic growthis misleading(Kessides 2007; Annez and Buckley 2009). As Kessides states: “Africa cannot simply be characterised as ‘u...