- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Psychiatry of Intellectual Disability

About this book

Comprehensive concise and easily accessible this is the first health economics dictionary of its kind and is an essential reference tool for everyone involved or interested in healthcare. The modern terminology of health economics and relevant terms used by economists working in the fields of epidemiology public health decision management and policy studies are all clearly explained. Combined with hundreds of key terms the skilful use of examples figures tables and a simple cross-referencing system between definitions allows the often complex language of health economics to be demystified.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Psychiatry of Intellectual Disability by Ashok Roy,Meera Roy,David Clarke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Medical Theory, Practice & Reference. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

General concepts

This section provides an introduction to the concept of intellectual disability. It provides definitions, classifications and information on prevalence, and it also lists the causes of intellectual disability, an understanding of which aids the development of preventive strategies.

Chapter 1

What is intellectual disability?

David Clarke

Introduction

In the early 1990s the Department of Health adopted the term learning disability as the successor to terms such as learning difficulty (which is still used with regard to the education of children), mental handicap, mental subnormality and mental deficiency. The term intellectual disability is gaining currency, and is used in the titles of academic journals circulated in the UK and elsewhere in Europe.

The term disability is preferable to handicap, because it describes the effect of lower than average intelligence in a manner consistent with the World Health Organization (1980) definitions of impairment, disability and handicap. An impairment is a loss or abnormality of structure or function, including psychological functioning. A disability is a restriction or lack of ability to perform an activity within the range considered normal for a human being. A handicap is a disadvantage resulting from an impairment or disability that limits or prevents the fulfilment of a normal role. In other words, a handicap is something which is imposed on a disability which makes it more limiting than it must necessarily be, just as weight or score handicap is added in horse racing or golf. The example of Lesch-Nyhan syndrome can be used to illustrate these concepts further. This is an X-linked genetic disorder (affecting only males), caused by a deficiency of the enzyme hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyl transferase. The enzyme deficiency (the disease) causes altered neuronal functioning (the impairment), resulting in learning disability and neuromuscular problems such as muscular stiffness and movement problems (the disability). The enzyme deficiency also results in a very unusual and severe form of self-injury in which affected individuals bite their fingers and lips, causing severe self-injury. Affected men often try to prevent such injury by self-restraint, as a result of which other people may avoid them in social situations and have low expectations of them (thereby creating a handicap).

The term learning disability is also preferred by some users of services. Others dislike most or all of the terms in use. Some service users and caregivers feel that terms such as ‘learning difficulty’ and ‘learning disability’ understate their problems, many of which have nothing to do with the ability to learn. One of the reasons for the changes in terminology over the years is that in time these terms acquired pejorative overtones, in a similar way to the term ‘spastic’ (a term that originally meant increased muscle tone). In the international scientific literature the term mental retardation is used. This has been defined as an intellectual impairment, arising in the early developmental period, which may lead to disability (if it significantly affects social functioning) or handicap (if the individual is totally dependent on special services). Mental retardation is the preferred term in North American countries, and has been adopted by the World Health Organization in the Tenth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) (World Health Organization 1992). Here it is defined as a condition of arrested or incomplete development of the mind, which is specifically characterised by impairment during the developmental period of skills that contribute to the overall level of intelligence. These include cognitive, language, motor and social abilities.

People with learning disability have an overall pattern of intellectual functioning at a significantly lower level than that of the general population, with associated impairments in social functioning. The cognitive impairment must have occurred during the period of cognitive development (in practice this is usually taken to mean before the age of 18 years).

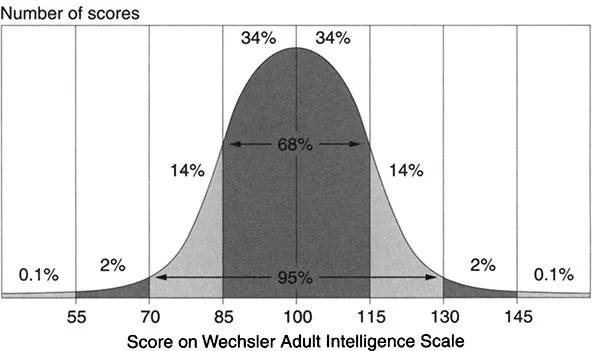

Tests such as the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale - Revised (WAIS-R) quantify different types of mental ability and group them as verbal and nonverbal scales. Subscales allow effects related to dysfunction of specific brain areas, educational underachievement, etc., to be assessed. The full-scale IQ score resulting from a WAIS-R test has been designed to compare the score of the person tested with the scores obtained from a large population of people of varying abilities. Subscale scores correlate with one another so that a person who scores high on one test tends to score high on the others. However, people with specific learning disabilities and those on the autistic spectrum may show a wide range of abilities. For example, a person with autism may be gifted in mental arithmetic but otherwise functioning in the range of learning disability. Two individuals with the same full-scale IQ may also have different profiles of abilities. The distribution of intelligence is illustrated in Figure 1.1.

Intelligence is normally distributed, like other attributes such as height and weight. This means that, in a typical population, most people will have scores close to average, with few people achieving very high or very low scores (see Figure 1.1). IQ tests such as the WAIS-R are therefore constructed and scored so that the average (mean) score is 100 and the standard deviation is 15 points. Anyone with a score greater than 2 standard deviations below the average (i.e. an IQ of less than 70) can be said to have a statistically significantly low IQ, provided that the test used is appropriate to the person tested and is properly conducted and scored. In some circumstances IQ tests do not provide an accurate assessment of cognitive ability. For example, it would be inappropriate to test a non-English-speaking person with verbal IQ test items in English. Similar considerations apply to other aspects of testing, such as the influence of cultural values and expectations. Despite these potential difficulties, IQ tests are the most accurate method of comprehensively assessing cognitive ability. They are widely used to decide, for example, whether people facing criminal charges should be dealt with through the criminal justice system or within the health service. They are not routinely used to assess cognitive ability in nursing, psychological or psychiatric practice, because less formal methods of assessing abilities and problems are usually more straightforward, less time consuming, less costly and just as effective. Other neuropsychological tests may be needed to obtain information about specific strengths or weaknesses. Assessments of practical skills (such as those carried out by occupational therapists with regard to everyday living skills) may be as important as or more relevant than assessments of global cognitive ability.

Figure 1.1 Distribution of scores on the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale

The approach adopted by ICD-10 with regard to classification of the severity of learning disability is to describe the typical abilities of people with specific severities of mental retardation (the term used in ICD-10), to allow a comparison with the person who is being assessed. This approach assumes uniformity with regard to the severity of problems (e.g. in self-care skills and language development), whereas some people with learning disability will inevitably have some areas of relative strength and other areas of relative weakness. Table 1.1 summarises the clinical descriptions of different severities of learning disability as outlined in ICD-10, and shows how these relate to the accepted categories of mild, moderate, severe and profound learning disability.

Table 1.1 Severity of learning disability and associated problems

Learning disability | IQ | Typical abilities |

Mild | 50-70 | Holds conversation. Full independence regarding self-care. Practical domestic skills. Basic reading/writing. |

Moderate | 35-50 | Limited language. Needs help with self-care. Simple practical work (with supervision). Usually fully mobile. |

Severe | 20-35 | Uses words/gestures to communicate basic needs. Activities need to be supervised. Work only in very structured/sheltered setting. Impairments in movement common. |

Profound | < 20 | Cannot understand requests. Very limited communication. No self-care skills. Usually incontinent. |

The concept of a mental age is considered by some professionals to be unhelpful. However, as a guide to the kinds of cognitive skills that are usually possessed by people with learning disability the concept has some utility, provided that its shortcomings are recognised. Adults with mild learning disability are said to have a mental age ranging from about 9 to 12 years. They are likely to have had learning difficulties at school, but many adults will be able to work and maintain good social relationships and contribute to society. Adults with moderate learning disabilities typically have a mental age of 6 to 9 years. They are likely to have shown marked developmental delays in childhood, but can often learn to develop some degree of independence in self-care and acquire adequate communication and academic skills. As adults they will need varying degrees of support to enable them to live and work in the community. Adults with severe learning disabilities have a mental age of between about 3 and 6 years and will probably always need support. Those with profound learning disabilities have a mental age of less than 3 years in adult life. They have severe limitations with regard to self-care, continence, communication and mobility (World Health Organization 1992).

It is important to note that, in clinical practice, a distinction is often simply made between mild learning disability (associated with an IQ of between 50 and 69) and severe learning disability (with an IQ below 50). In most post-industrial societies people with an IQ of less than 70 are placed at a relative economic (and hence social) disadvantage, and anyone with an IQ below 50 would be most unlikely to be able to live independently or obtain employment. For people with IQs of between 50 and 70, much depends on other factors such as their personality, coping strategies and family support. Some people with mild learning disability do not receive health or social services. The degree to which someone is disadvantaged or ‘handicapped’ by a learning disability therefore depends on social and cultural factors (and the nature of any associated problems) as well as on the severity of their global cognitive impairment. One of the disadvantages of a label such as ‘learning disability’ is that it encompasses people with very different problems and needs. Some will have a genetic or chromosomal disorder associated with particular physical (and sometimes behavioural) problems, while others will only have learning problems. Some will have learning problems, but their quality of life will be dependent on factors such as the control of epileptic seizures rather than receipt of services to help with learning problems. However, labels such as ‘learning disability’ (and diagnoses such as autism or Down syndrome) are helpful in some ways. They provide an ‘explanation’ of problems, they may reduce feelings of guilt, they may facilitate the provision of appropriate services, and they may serve as an aid to communication between service providers.

How common is learning disability?

The frequency of occurrence of conditions among populations of people is often described in terms of incidence (the number of people newly identified as having a condition) or prevalence (the number of people identified as having the condition at a particular time or over a defined length of time). For learning disability, the incidence is often described for specific disorders (e.g. Down syndrome) as the proportion of live-born infants ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- About the editors

- List of contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Part 1 General concepts

- Part 2 Clinical aspects

- Part 3 Meeting the need

- Index