- 488 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Chemical Discovery and Invention in the Twentieth Century

About this book

First published in 1919. Tilden discusses a compilation of chemical discovery and invention to demonstrate the progress of chemistry in the early 20th century. Divided into 5 sections, chemical laboratories and the work done in them, modern discoveries and theories, modern applications of chemistry, and modern progress in organic chemistry, the author presents an overview of the subject. The final section of the book contains an account of important discoveries which find practical applications and provide new views of the constitution of the world in which we live.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Chemical Discovery and Invention in the Twentieth Century by Wiliam A. Tilden in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Chemical Laboratories and the Work Done in Them

Chapter I

Laboratories for General Teaching

THE word laboratory, which merely signifies a workshop, has by long custom been applied chiefly to the room or building in which chemical experiments are carried on, or at any rate experiments in natural science in which operations more or less chemical in character are practised.

The chemists of the past were content with very modest accommodation, provided a sufficient amount of light was secured together with a supply of water and the means of obtaining heat. Berzelius, the famous Swedish chemist, who lived till 1848, carried out the greater part of his accurate estimations of atomic weights as well as other researches in a room communicating with the kitchen of his house, where Anna his servant maid acted as his only assistant.

At this time the teaching of chemistry in the universities was everywhere conducted solely by the method of lectures which were rarely enlivened by experimental demonstrations. The student desirous of learning something of chemical analysis or other practical chemical work had to seek the privilege of admission into the private laboratory of some professor of chemistry. Liebig tells us that he had to leave his own country, Germany, where in his youth there were no chemists of any importance, in order to apply to Gay-Lussac in Paris for permission to work under his direction. With this experience in his mind it is not surprising that on his return home two years later he should have determined to found in his own country an institution in which students could be instructed in the art and practice of chemistry, in the use of chemical apparatus, and the methods of chemical analysis. Such was the origin of the famous laboratory at Giessen which, from 1824 onwards, for many years attracted students from every civilised country. It was but a modest place with none of the appliances with which we are now familiar.

It was twenty years later before a laboratory for instruction in chemistry was opened in this country, and even then it was not either Oxford or Cambridge which took the lead in this important reform.

The first laboratory in this country opened for the use of students of chemistry was provided by the Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain at their premises in Bloomsbury Square. In 1844 places were furnished for twenty-one students. The laboratory was a single apartment, the ventilation of which was very imperfect, and as many of the operations required the use of coke furnaces the place was full of smoke and fumes. Almost immediately after this the Royal College of Chemistry was founded, and for the first year or so carried on operations in George Street, Hanover Square. It was then transferred to its permanent home in Oxford Street, where a building had been provided which still exists, and, with an additional upper storey, contains the offices of the General Medical Council. The building had a frontage of only 34 feet with a depth of 53 feet.

The whole of the first floor was occupied by the Students’ laboratory, while on the ground floor were a private laboratory for the Professor, a balance room, and a lecture room at the back. The basement contained furnaces and a steam-boiler and stores.

It is unnecessary to pursue this retrospect any further, for the example set at Giessen, when once the movement had begun, was followed in all the great centres of instruction. But even the new laboratories were very inferior in size and equipment to those which have been erected in more recent times.

The rate of progress during the last thirty or forty years has been very rapid, and stimulated by the rivalry between nations and by the rapidly increasing numbers of students seeking instruction, the buildings provided for the accommodation of the chemical departments in the universities and modern colleges as well as the numerous technical schools, have gradually assumed more and more palatial features. The first important step in this direction was taken by the German Government, when, after the Eranco-Prussian war in 1870–71, Strassburg became a German town.

Possibly animated by the desire to placate the Alsatian population, splendid separate institutes were erected in Strassburg to provide for the several branches of science, chemistry, botany, geology, etc. Each of these institutes contained accommodation, on a scale previously unknown, for laboratories, lecture rooms, and museums, as well as residence for the chief professor. Even the Strassburg chemical institute is now surpassed in dimensions and outfit by some of the establishments more recently erected in various parts of the world.

Before proceeding further it will be convenient to review the purposes for which the very numerous chemical laboratories have been erected in all the civilised countries of the world. In the first place it must be remembered that they are not all devoted to the purposes of instruction. Many are occupied with purely practical objects in connection with analysis of products for control of quality, or for fiscal purposes, or in association with manufacturing operations. And in these later times the importance of research is becoming so generally recognised that institutions have been founded and endowed with the sole object of providing facilities for carrying on such work independent of teaching, on the one hand, and of industrial or practical purposes on the other. The following classification of laboratories must be understood to be only illustrative, and with a few exceptions applies only to the British Isles. The total number of universities and of technical schools in Britain alone is very large, and any attempt to enumerate completely even these would require a volume to itself. The reader must be informed therefore that if the universities of other countries and such famous technical schools as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology at Boston, are not included in the analysis it is from no want of sense of their importance.

Laboratories For Instruction

- Universities (15 British).

- University Colleges.Special Departments for Agriculture ; Brewing ; Dyeing ; Leather ; Metallurgy.

- Technical Schools.Among the most important are : The Imperial College at South Kensington ; The Royal College of Science, Dublin ; The City and Guilds of London, Finsbury ; The Pharmaceutical Society ; The Royal Technical College, Glasgow ; The Municipal School of Technology, Manchester.

- Agricultural Colleges.

- Public Secondary and Elementary Schools.The laboratories in some of the great public schools of England are now as well equipped as those of the universities.

Laboratories For Analysis (Chiefly)

- Government Laboratories.Central ; Admiralty ; Woolwich Arsenal ; Imperial Institute.

- Public Analysts.

- London County Council.

- Many private analytical.

Laboratories Connected With Manufactures

These are private establishments connected with individual works for the production of iron and steel and metals generally, also with alkalis and acids, drugs, dyes, and chemical products of all kinds. One which is at the present time attracting much attention is the laboratory for research financed by the Government for the assistance of “British Dyes Limited.”

Laboratories For Research Only

The Royal Institution, established under Royal Charter 1800. With it is associated the Davy-Faraday Laboratory, founded and endowed by the late Dr. Ludwig Mond.

The Lister Institute, corresponding in aims with the Pasteur Institute in Paris.

The National Physical Laboratory, dealing with metallurgical research among other subjects, chiefly physical and mechanical.

The Lawes Agricultural Trust. Experimental Station and Laboratories, Harpenden, Herts.

The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry, opened October 23, 1912, at Dahlem, near Berlin.

A few of the more important of these will now be described.

I—The Imperial College of Science And Technology, London

One of the largest and most completely equipped chemical departments was erected by the British Government for the accommodation of the Royal College of Science and Royal School of Mines at South Kensington, London, and was occupied for the first time in 1906. The architect of the building was Sir Aston Webb, R.A., but the arrangement and fittings of the interior were designed by the then professor of chemistry, the present writer.

A general view of the exterior of the principal building is shown in Fig. 1, from which it will be seen that it consists of a central block with two wings. The eastern half of the building is devoted wholly to chemistry, while the western half is occupied wholly by physics. The central mass contains the entrance and stairs leading to upper stories occupied by the Science Library which forms a part of the South Kensington Science Museum. This provision for pure chemistry is supplemented by the Department of Fuel and Chemical Technology, of which the separate building has been more recently erected and occupied for the first time in 1915. The College and the School of Mines are now united, together with the City and Guilds of London Institute, into one chartered body, the Imperial College of Science and Technology.

FIG. 1.—Imperial College of Science and Technology, London. Departments of Chemistry and Physics.

The buildings contain complete suites of laboratories, lecture rooms, and accessory apartments, with accommodation for the teaching staff in the four divisions of

- General and Analytical Chemistry ;

- Physical Chemistry ;

- Organic Chemistry ;

- Fuel and Chemical Technology.

There is a professor at the head of each division, with a number of assistants.

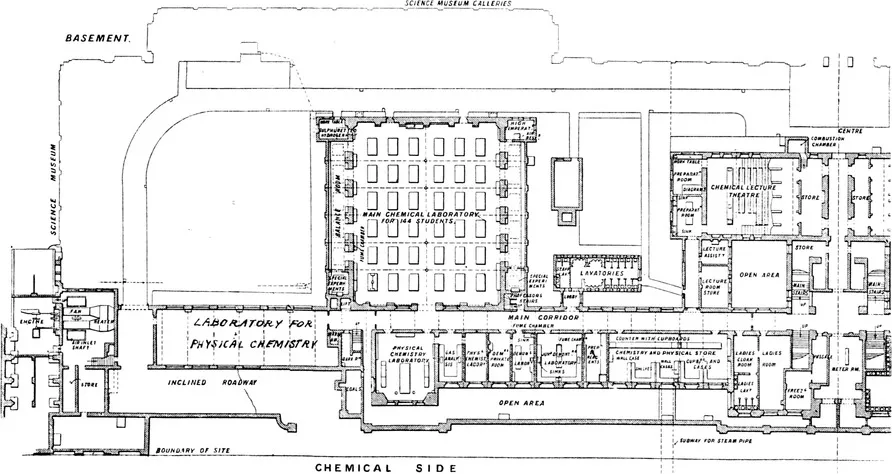

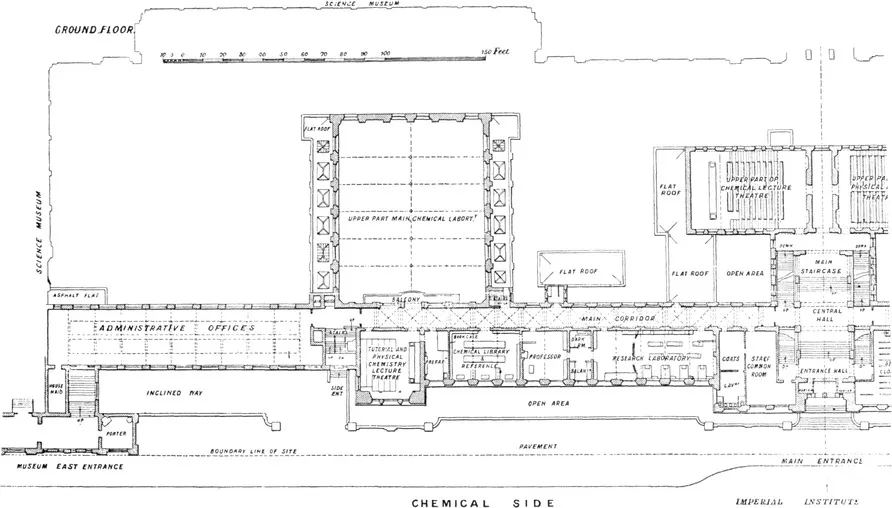

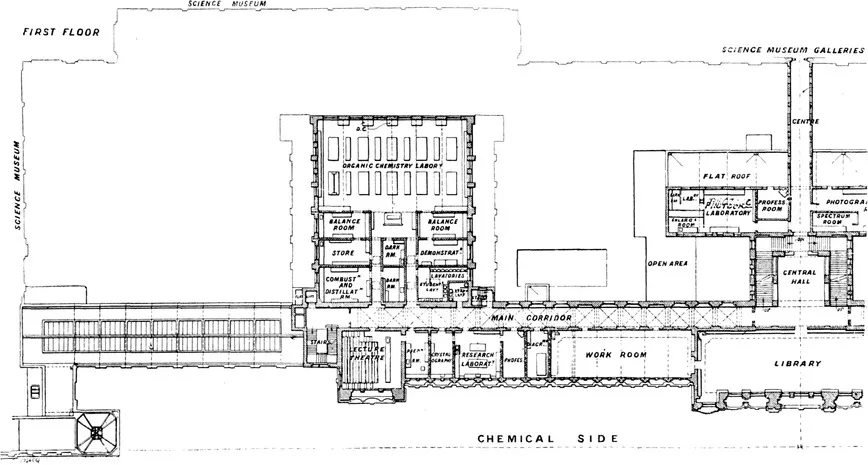

As the internal arrangements are typical of what is aimed at in many chemical institutions it will be worth while to glance at the plans of the several floors which are shown in Figs. 2, 3 and 4, which show respectively the basement, the ground floor, and the first floor.

FIG. 2.—Imperial College of Science and Technology, London. Departments of Chemistry and Physics.

FIG. 3.

FIG. 4.

From the main entrance stairs descend on the left to the lower ground floor, upon which level are found the chief lecture theatre, the large chemical laboratory, with separate places for 144 students, and the series of laboratories for physical chemistry. The balance rooms for the big laboratory extend along each side of the building, access being provided at five points on each wall. The lecture theatre provides comfortable sitting space for 150 students, but there is a large floor at the back and considerable room in front, so that about twice that number of auditors can be provided for when occasion requires. At the back of the table are blackboards, means of hanging diagrams, and two screens for projected pictures or lantern views of experiments. There are several wide pipes leading downwards from the surface of the table by which even copious fumes can be sucked away and prevented from reaching the audience. There are also numerous connections, visible in the picture, by which water, gas, electric current, and vacuum can be at once utilised for experiments to be shown on the table. The room can be rendered completely dark, when necessary, by the provision of black blinds to all the windows.

In addition to these there is a spacious store for physical and chemical apparatus, of which a large quantity in the form chiefly of glass flasks, beakers, and other necessary vessels is always kept in stock. Close at hand is the freezing room, in which there is a machine, electrically driven, for the production of liquid air.

Ascending to the floor above there is a series of apartments which provide a lecture room with seats for about fifty students, chiefly occupied by the professor of physical chemistry, a library of reference furnished with the principal chemical periodicals, dictionaries, and other large special treatises. Adjoining this is the private room for the professor of general chemistry, who is also director of the laboratories, and this leads to his research laboratory, where there is room for about eight or ten workers. The floor above this, called the first floor, is occupied almost entirely by the professor of organic chemistry who has a separate research laboratory. A room, also close by, is occupied...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Part I Chemical Laboratories and the Work Done in Them

- Part II Modern Discoveries and Theories

- Part III Modern Applications of Chemistry

- Part IV Modern Progress in Organic Chemistry

- Appendix

- Index